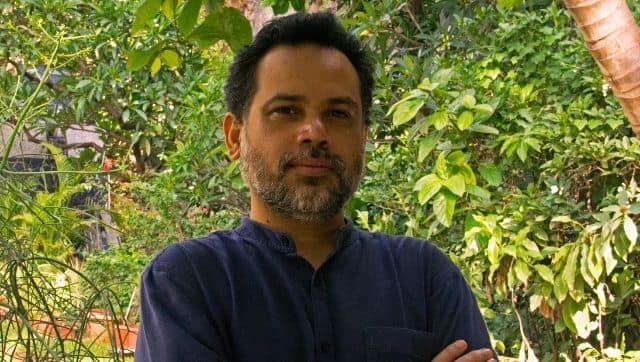

Writer and director Sidharth Singh’s debut novel Fighter Cock tells the story of Sheru, a small-time thug who escapes the underbelly of Mumbai and goes into hiding in the fictional rural province of Shikargarh. Through Sheru’s adventures, the screenwriter frames a satirical narrative that describes a culture doused in patriarchy in which a debauched Maharaja, stripped of his titles, continues to assert power over his villagers in post-independence India. Set against the backdrop of the fierce cockfighting competitions that are rapidly drowning the men of this region into dangerous debts and addiction, Singh’s western acts as a parody of the male-dominated hegemonic structures that not only oppress those on the lower rungs of this ladder but also pit dominant men against each other in a superiority contest. In a conversation with Firstpost, the author talks about growing up in an erstwhile rural princely state in Bihar, the hyper-masculine setting of his novel and how he reduces patriarchy to its crudest form by using cockfighting as a metaphor for the power play in the hinterland of Shikargarh. Edited excerpts: *** How did your debut novel, Fighter Cock come about and what prompted the move from writing for film and television to writing this book? I had been toying with the idea of a western for over a decade and had initially envisioned Fighter Cock as a film, but I found no takers for it. Finally, around the end of 2018, there was a strong urge to get this story out of my system and I was compelled to reimagine it as a novel. It just came from my gut. According to you, which are a couple of major differences in the process of writing for the screen and writing for a novel? Additionally, did the pandemic-induced lockdown and social distancing give you more time to focus on developing this story? In screenwriting, every word needs to propel the dramatic action forward and whatever is unnecessary gets cut out. Scripts are said to be good when there’s more white than black on the page. Besides the story, scripts contain an imagined realm beyond the written word which will eventually come to life on screen with locations, performance, music and cinematography, so one has to accommodate the interests of other collaborators, as the script is just one part of the whole. In a novel all that goes out of the window. It’s a complete work in itself. There’s no collaboration (besides with the editor, in my case) and no other realms to consider other than the written word. I found that extremely liberating. I had finished writing the first draft just before the pandemic hit us. The subsequent drafts were done ensconced at my parents’ farm in Dumraon, in rural Bihar. It was great being back in the countryside on an extended visit and I think that really helped me to illuminate the rustic aspects of the story with more authenticity. [caption id=“attachment_9789861” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Fighter Cock marks screenwriter and director Sidharth Singh’s debut novel.[/caption] Fighter Cock is set in the wilderness of central India where locals operate under the influence of a debauched raja, even in the contemporary age. How does such a rustic countryside and its wilderness play into the overall narrative of a dark, male dominated region in which conflict and contest prevail? There are two worlds in Fighter Cock. One is the rugged, feudal world of Shikargarh and the other is the rough underbelly of Bombay. Both the worlds are dark and male dominated, and the protagonist, Sheru, is a product of the clash of these hyper-masculine worlds. All this is told using the standard western tropes of troubled stranger, arrives in one-horse-town, is forced to confront existing power structures.

Fighter Cock marks screenwriter and director Sidharth Singh’s debut novel.[/caption] Fighter Cock is set in the wilderness of central India where locals operate under the influence of a debauched raja, even in the contemporary age. How does such a rustic countryside and its wilderness play into the overall narrative of a dark, male dominated region in which conflict and contest prevail? There are two worlds in Fighter Cock. One is the rugged, feudal world of Shikargarh and the other is the rough underbelly of Bombay. Both the worlds are dark and male dominated, and the protagonist, Sheru, is a product of the clash of these hyper-masculine worlds. All this is told using the standard western tropes of troubled stranger, arrives in one-horse-town, is forced to confront existing power structures.

In Shikargarh, I wanted to bring alive the blatantly feudal hinterland, whose existence we tend to ignore, sitting in the comforts of our urban, gated communities. I wanted it to be a wild, patriarchal, over-the-top version of the so-called badlands, juxtaposed with the Bombay underbelly that we all know well.

Could you elaborate on the need to frame more and more narratives which focus on provincial India and the issues that the people of these regions continue to battle? Though I haven’t read much Hindi literature, I’m aware that there is a lot of writing in Hindi and other regional languages that deals with provincial life, but most of these works don’t get translated into English. Hindi cinema has also portrayed provincial life effectively, right from films like Do Beegha Zameen to Sholay, Omkara and Gangs of Wasseypur. So I think this need to frame more narratives in provincial India is peculiar to Indian writing in English, whose presumably urban readership may be getting disconnected from the hinterland as it increasingly comes under the sway of a homogenising, global content culture. What I have tried to do with Fighter Cock is use a western pop culture style, to tell a very desi story. The fighter cocks and the conflict between the Karianath and Aseel varieties themselves stand for two dominant forces going against each other in the story. What was your motivation behind using the animals as a symbolism to critique these structures? I wanted to reduce patriarchy down to its crudest form, which is why the book is full of phallic symbology. The roosters, the cannon and the fort itself, are all symbols of masculine obsessions with power. Earlier, as a sports broadcaster I used to produce live shows on horse racing where I learnt that the races are essentially a showcase for bloodstock trading, which is where the real money and prestige of the sport lies. The racecourse is just a playground for the big boys to show off their studs. Similarly, cockfighting is an ancient bloodsport that gives men a big kick. Roosters have traditionally been associated with virility, so the world of cockfighting fit in seamlessly with the hyper-masculine setting at various levels. The undercurrents of the supernatural like djinns, the Devta and even dreams and intuitions make for another layer of mystery and intrigue built into the story. Why have you chosen to add these flourishes to the book? Though Shikargarh is completely fictional, I wanted the book to evoke a sense of place, which would allow the readers to immerse themselves in that world. In order to do that, I fabricated aspects of the region’s history, geography and folklore to lend an absurd credibility to the place. Once the landscape and its culture were established, I found it funny and interesting to give it a voice in the form of the Devta, the djinns and the malevolent Bhookhi Hawa. People in the hinterland are very closely associated with the land and their village deities and I wanted that to reflect somewhere in the story. Much of your story is centred on bloodlines and how familial relationships continue to be exploited for politics and power. The novel does suggest how the younger generations inevitably end up paying for the sins of their ancestors. According to you, do bloodlines and the important role they play, in fact end up fostering the existence of hegemonic patriarchal structures? In my limited experience, what I have observed is that the patriarchal system propagates certain beliefs and notions, which are packaged under the overarching word ‘tradition’ and handed down the generations, with little regard to the evolving cultural context of the age. What it does, is reinforce a false sense of superiority and entitlement among later generations, which results in unnecessary squabbling. That is how the younger generations pay for the sins of their ancestors. However, the novel only takes a light-hearted dig at this. Could you elaborate on the research and readings that went into creating this story? Which were some of the materials or writings that you referred to while crafting this rural setting and the characters that inhabit the province? I come from a place called Dumraon in rural Bihar, which was an erstwhile princely estate ruled by my ancestors, so I know the feudal world very well. I grew up on a farm and boarding school in Dehradun, in a very outdoorsy life, reading a lot of westerns by Louis L’amour, the shikar tales of Jim Corbett and stuff like that. There were also cinematic influences of westerns, martial arts films and Bollywood gangster dramas. In later years, books like Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad, One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Breakfast of Champions by Kurt Vonnegut and In an Antique Land by Amitav Ghosh had a big impact on me, as did the films of Quentin Tarantino, the Coen Brothers and Werner Herzog. I think at some level, writing Fighter Cock was an exercise to purge myself of all these influences and conditioning, to get them out of my system so that I could move on to other things. In all humility, I wrote it off the top of my head with minimal research on cockfighting. Sidharth Singh’s Fighter Cock has been published by Penguin Random House India

)