Ameya Narvankar, who works as a user interface and user experience designer with a multinational company in Bengaluru, feels that the fear of “Log kya kahenge?” (What will people say?) keeps many Indians from accepting the LGBTQ+ people in their lives. He has written a children’s book titled Ritu Weds Chandni to tell a delightful story of two women in love who decide to get married with great fanfare, and the support of their families and friends. When people offended by this decision try to disrupt the wedding, a little girl named Ayesha comes up with a unique idea to ensure that the festivities proceed as planned. The book was first published in the US by Yali Books in 2020, and it has been published in India in 2022 by Puffin Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House. The title of your book sounds like an invitation to a wedding. It seems perfect in keeping with the overall voice and feel, which welcomes readers into the world of queer love rather than reprimanding them for their homophobia. Is this how you intended it to be? Yes, absolutely! I wanted to write a happy love story. I wanted the queer characters in my book to get their happy ending.

During my interactions with people from the queer community, I often heard this question: “Why does representation always have to be tragic?” I took that into account, especially because it is a book for children.

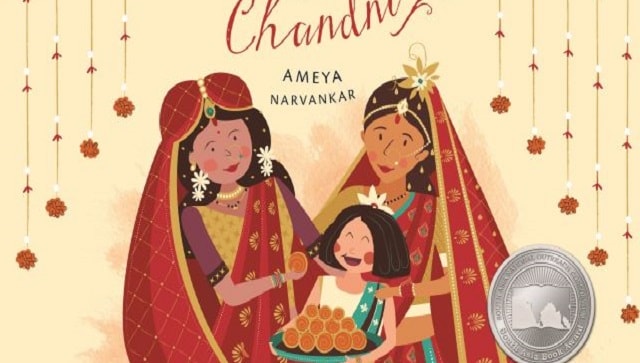

I wanted to keep it light without any sugarcoating so I addressed the homophobia before giving them a happy ending. Through the title, I wanted to remove all ambiguities about the content of the book. I played around with many titles. There was a time when I thought of calling this book The Two Brides but that could have led to some confusion. It could have made people think that the book was about two sisters getting married at the same time. The current title leaves no scope for misinterpretation. In fact, an earlier version of the book was designed like a wedding card. It is great to see an Indian queer love story where parents are not standing in the way of their children’s happiness. Is children’s publishing in India more ready for a story like this today than it was before Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was read down? Yes, certainly! When I wrote the first draft of the book, Section 377 was still in place. It was read down only in 2018. I began to approach publishers right after my graduation in 2016. Many of them did not respond. Those who responded told me that they already had a line-up for the next three years. I think that they were too polite to reject my proposal outright. I understood that they were apprehensive, and this was mainly because of Section 377. In the last few years, children’s publishers in India have published queer stories. I think that Bollywood opened many doors when it comes to popular representation of LGBTQ+ people. Your book was first published in the US in 2020. How was it received by children, parents, teachers, librarians, and particularly people of Indian descent who live there? Ritu Weds Chandni got a good reception there in terms of numbers. Yali Books, my US publisher, sold 2,500 copies, which is great considering it is an independent publishing house printing books on demand. I have had parents and teachers reaching out to me with words of appreciation, and that has been encouraging because they are the gatekeepers for children. Sapna Pandya, a queer pandita who officiates LGBTQ+ weddings, did a public reading. The book got added to the 3rd-5th Grade GLSEN Rainbow Library Book List. GLSEN is an organisation that advocates for schools to be safe and inclusive for LGBTQ+ students. It was selected as a 2021 Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People by the National Council of Social Studies and the Children’s Book Council, and a Top Ten Book by the American Library Association’s Rise: A Feminist Book Project. The 2021 South Asia Book Award for Children’s and Young Adult Literature named it one of their ‘honour books.’ [caption id=“attachment_10337801” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Book cover of Ritu Weds Chandni[/caption] Have you made any changes to the text and the illustrations for the Indian edition? Yes, there are some differences between the American edition and the Indian one. For the American one, I did not establish any geographical context for the story in terms of visual cues but the brides were presented as desi American women. I included a glossary to help readers understand common Hindi words like baraat, lehenga, mehendi, chachi, tilak, and laddoos. Parents and educators in the US appreciated this back-of-the book content because it gave them ways to help the children understand the culture the story comes from. The Indian edition with Penguin has a section on what it means to be an ally. It wasn’t in the US one. This section will hopefully make parents and teachers more comfortable in sharing the book with children, and answering follow-up questions that they might have about the story. Tell us about your thesis project at IIT Bombay, the starting point for this book. I did a two-year Masters in Design (MDes) in Visual Communication at the Industrial Design Centre at IIT Bombay. This was from 2014 to 2016. Those years were a really significant part of my journey as a queer person. I had accepted myself earlier but being in an open and free environment helped me come out to others. IIT Bombay has an LGBTQ+ resource group called Saathi. I joined it, and shared my design skills. It was great to be on a campus where many people were out. My thesis project grew out of this whole experience. My topic was ‘Visibility and Representation of LGBTQ+ People in Indian Society.’ I looked at films, media, and children’s literature. I spoke with LGBTQ+ community members, teachers, and psychologists. I came to the conclusion that children are not born homophobic; they learn homophobic behaviour from people around them. Children’s literature is one of their earliest windows into the world, so I decided to focus on LGBTQ+ visibility and representation in children’s books. My thesis advisor was Professor Sudesh Balan. I also reached out to Professor Nina Sabnani a few times because she specialises in animation and illustration. All the students had to formulate a design problem based on their research, and then come up with a solution. The book Ritu Weds Chandni was the physical outcome of my research work. I saw it as a small contribution towards changing mindsets about LGBTQ+ people in India. After I presented my thesis, I came out to my professors, and they were very supportive. It gave a boost to my confidence but I was not sure if the book would get published. I got many rejections from Indian publishers, so I was thrilled when Yali Books agreed to publish it. Why did you choose to have a child narrate this story? Ayesha in your book reminded me of Ahmed in Pakistani Canadian author Eiynah’s book My Chacha is Gay [2014]. Children usually find it easier to place themselves in the shoes of a protagonist if this person is of the same age as them. Children have their own lens, and a lot of innocent questions, so I thought that it would be great to tell the story through the perspective of a child like Ayesha. While conceptualising this character, I took my friends’ children as a reference point. Ritu Weds Chandni comes at a time when petitions to legalise same-sex marriage have been filed in the Delhi High Court and the Kerala High Court. Do you think that your book might be able to soften the hearts of Indians who are opposed to such marriages? Yes, that is my intention. Mindsets do not change immediately when there are legal reforms. There have to be parallel efforts along with the legal process to change how people think. What made you give your characters a religious wedding rather than a court marriage? I thought that children would not be familiar with court marriage as a concept but a traditional wedding would be easy to relate to since children are taken to such weddings even as babies. I also wanted to show that customs can be adapted if people are open-minded. Tell us about visual references from Bollywood that you used while illustrating it. The song ‘Saajan Ji Ghar Aaye’ from Karan Johar’s film Kuch Kuch Hota Hai [1998]! In an interview with the Jewish Women’s Archive in 2020, you said, “The baraat stands in for a pride parade.” Could you please help us unpack this statement? Despite the threats that Ritu and Chandni receive, they decide to go ahead with the wedding. They do not want a hush-hush ceremony. They want to proclaim their love for each other in the open, get on horses, and have friends and family in their baraat celebrate this moment. They want to assert their queer identity, so I could draw parallels with a pride parade. In my earliest draft, I had some evil men in the story who were called the moral brigade. As the book shaped up, some of the things that seemed cool to me earlier began to look silly. Even in visual terms, a baraat undoubtedly looked more appealing than a car with a sunroof. [caption id=“attachment_10337821” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Ameya Narvankar[/caption] The subject of same-sex marriage evokes various reactions even among queer people. Many queer activists in India believe that issues like housing, police brutality, and healthcare are far more urgent than legalisation of marriage. What are your thoughts on this? I think that all of these battles need to be waged, and they can run parallel to each other. Even when my partner and I look for a house to rent, we are told by people that they rent only to families, and not to bachelors. I feel like shouting at them, and saying that my partner and I are a family. We have been living together. Funnily, some people think we are brothers. Since same-sex marriage has not been legalised in India, many couples face this problem. Your bio sketch in the American edition says that you love cats, bearded men, and Beyonc****é. Have you thought of working on a book that has all three elements? I hadn’t thought of this earlier but it is a fabulous idea. If I work on it, I will credit you. Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist, and book reviewer.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)