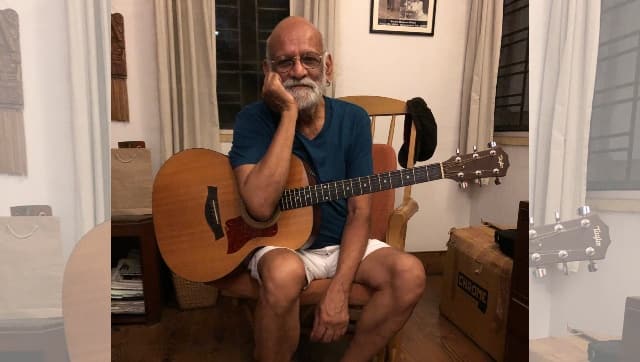

“I’m a walking, talking contradiction, living in an age of fiction,” sings Susmit Bose, the 71-year-old Kolkata-based songwriter, who has earned himself the title of ‘India’s Bob Dylan’. An urban folk musician, Bose has been composing songs of hope and change, songs that deal with social issues such as human rights, global peace and non-violence since the 1970s. Born in Ahmedabad, Bose is the son of a renowned Hindustani classical musician and a musicologist. When the family moved to Calcutta, he was constantly surrounded by dancers, musicians, film actors, artists and theatre folk. He dreamed of one day becoming Pandit Susmit Bose. But life had other plans. “I grew up in a family where music was essential. My father was with the All India Radio and setting up radio stations all over the country, so we were constantly being transferred. We settled down in Delhi in 1960, and by then, all my siblings were learning music and dance. But my father was dead set against me picking it up,” says Bose, whose exposure to folk and tribal music started in the recording studios his father took him along to. [caption id=“attachment_9776081” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

In 1978, Bose released his first album Train to Calcutta, the first original English album to have come out in India.[/caption] “When musicians visited, I would just sit outside the room, put my ear to the door and listen to how these great masters would phrase things, which in Hindustani music is called ‘bol banao’. When there were concerts, I’d go backstage with Baba and say hi to all the big guys like Bhupen Hazarika and Ravi Shankar.” But within the patriarchal structure, his wish to learn classical music was closed off. “I was a very timid and under-confident boy. It was an unfulfilled dream that was creating a lot of desperation in me.” As fate would have it, his tryst with folk music finally began at the age of 13 at Springdales School. During a school pageant, he heard the words ‘I can see a new day. A new day soon to be. When the storm clouds are all passed. And the sun shines on a world that is free,’ on the PA system. “My hair stood up,” recalls Bose, “I needed to know where this sound was coming from. I went to the booth and when I asked my music teacher Byomkesh Banerjee who the singer was, he just gave me an album. I saw this tall, lanky man in front of a microphone playing a banjo. I didn’t even know what a banjo was. That was my introduction to Pete Seeger." By this point, Bose had found a guitar and was teaching himself how to play it. The school’s principal, whose daughter is now Bose’s wife, was a kind lady and often invited him to listen to records and talk about music, civil rights and movements of resistance. The troubadour songwriter in him was thus born — he’d found his calling. He dropped out of college, experienced Transcendental Meditation and the hippie life in Kathmandu, and was deeply immersed in anti-establishment and anti-patriarchy thought. “The ’70s were dichotomous times. There was the Vietnam War, the man on the moon. There was the women’s liberation movement, Nirvana and the hippie movement. We were angry and wrote songs to make a statement.” Bose started his career performing covers at nightclubs. It was his debut song ‘Winter Baby’ which shot him to fame. At 21, he received his first contract from a hotel asking him to perform regularly. But within a year’s time, he was fed up. “At that age, coming from a kind of middle class background, you got absolutely corrupted by the glamour, money, press, fame. So I walked away from performing.” In 1978, he released his first album Train to Calcutta, the first original English album to have come out in India, which featured songs about social issues. In the following years, Bose performed all across the globe. He participated in the International Folk Song Festival in Havana, Cuba. He started corresponding with his hero, Pete Seeger, whom he had the honour of singing on the same stage with in Newark in 1981. “We agreed to perform [Woody] Guthrie’s ‘This Land is Your Land’. So he’d sing ‘From California to the New York Island’ and I was singing ‘From High Himalaya to Cape Comorin’. It was wonderful,” Bose shares. He recalls Seeger’s first letter after listening to Train to Calcutta, which said ‘OVERWHELMED’ in bold letters. He also received a cheque of $40, which he never encashed. Bose worked sporadically on his music in the 80s and 90s. He worked on jingles, started his own ad agency called Track and then started making films. “I got to be a part of a huge Doordarshan serial called Surabhi, which had short stories on folk and tribal art and culture in India.” In 2005, his friend Rukmini Shekhar who runs the Viveka Foundation roped him back into the music world. “I kickstarted my second phase of recording from 2005 to 2010. For Public Issue, my 2005 comeback album, nobody took a penny from me to record it… All my albums were commissioned. I did a United Nations 50 years concert in Delhi. I curated an album on AIDS for the UNDP. I did a baul album for the Ford Foundation. But then I said, ‘It’s been 40-50 years of this,’ and I walked away again,” he says. When asked about the influences in his music and life, Bose replies, “The Hindustani classical musicians, Baba included; Pete Seeger, Dylan and the Guthries; and the Bauls. Each one had a role to play. From the Hindustani classical musicians, I learned how to phrase my words to reach out through my singing. Dylan gave me cynicism and hardheadedness. The harmonica was a straight take-off from the Guthrie family. And I learnt bohemia, voice modulation and string plucking from the Bauls.” [caption id=“attachment_9776091” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

In 1978, Bose released his first album Train to Calcutta, the first original English album to have come out in India.[/caption] “When musicians visited, I would just sit outside the room, put my ear to the door and listen to how these great masters would phrase things, which in Hindustani music is called ‘bol banao’. When there were concerts, I’d go backstage with Baba and say hi to all the big guys like Bhupen Hazarika and Ravi Shankar.” But within the patriarchal structure, his wish to learn classical music was closed off. “I was a very timid and under-confident boy. It was an unfulfilled dream that was creating a lot of desperation in me.” As fate would have it, his tryst with folk music finally began at the age of 13 at Springdales School. During a school pageant, he heard the words ‘I can see a new day. A new day soon to be. When the storm clouds are all passed. And the sun shines on a world that is free,’ on the PA system. “My hair stood up,” recalls Bose, “I needed to know where this sound was coming from. I went to the booth and when I asked my music teacher Byomkesh Banerjee who the singer was, he just gave me an album. I saw this tall, lanky man in front of a microphone playing a banjo. I didn’t even know what a banjo was. That was my introduction to Pete Seeger." By this point, Bose had found a guitar and was teaching himself how to play it. The school’s principal, whose daughter is now Bose’s wife, was a kind lady and often invited him to listen to records and talk about music, civil rights and movements of resistance. The troubadour songwriter in him was thus born — he’d found his calling. He dropped out of college, experienced Transcendental Meditation and the hippie life in Kathmandu, and was deeply immersed in anti-establishment and anti-patriarchy thought. “The ’70s were dichotomous times. There was the Vietnam War, the man on the moon. There was the women’s liberation movement, Nirvana and the hippie movement. We were angry and wrote songs to make a statement.” Bose started his career performing covers at nightclubs. It was his debut song ‘Winter Baby’ which shot him to fame. At 21, he received his first contract from a hotel asking him to perform regularly. But within a year’s time, he was fed up. “At that age, coming from a kind of middle class background, you got absolutely corrupted by the glamour, money, press, fame. So I walked away from performing.” In 1978, he released his first album Train to Calcutta, the first original English album to have come out in India, which featured songs about social issues. In the following years, Bose performed all across the globe. He participated in the International Folk Song Festival in Havana, Cuba. He started corresponding with his hero, Pete Seeger, whom he had the honour of singing on the same stage with in Newark in 1981. “We agreed to perform [Woody] Guthrie’s ‘This Land is Your Land’. So he’d sing ‘From California to the New York Island’ and I was singing ‘From High Himalaya to Cape Comorin’. It was wonderful,” Bose shares. He recalls Seeger’s first letter after listening to Train to Calcutta, which said ‘OVERWHELMED’ in bold letters. He also received a cheque of $40, which he never encashed. Bose worked sporadically on his music in the 80s and 90s. He worked on jingles, started his own ad agency called Track and then started making films. “I got to be a part of a huge Doordarshan serial called Surabhi, which had short stories on folk and tribal art and culture in India.” In 2005, his friend Rukmini Shekhar who runs the Viveka Foundation roped him back into the music world. “I kickstarted my second phase of recording from 2005 to 2010. For Public Issue, my 2005 comeback album, nobody took a penny from me to record it… All my albums were commissioned. I did a United Nations 50 years concert in Delhi. I curated an album on AIDS for the UNDP. I did a baul album for the Ford Foundation. But then I said, ‘It’s been 40-50 years of this,’ and I walked away again,” he says. When asked about the influences in his music and life, Bose replies, “The Hindustani classical musicians, Baba included; Pete Seeger, Dylan and the Guthries; and the Bauls. Each one had a role to play. From the Hindustani classical musicians, I learned how to phrase my words to reach out through my singing. Dylan gave me cynicism and hardheadedness. The harmonica was a straight take-off from the Guthrie family. And I learnt bohemia, voice modulation and string plucking from the Bauls.” [caption id=“attachment_9776091” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

I knew you couldn’t change the world overnight. I just tried to emphasise the ideology of peace and anti-war, says Bose.[/caption] In his 50-year career, Bose has seen how the music industry has changed. “Before the idea of consumerism, music meant something. You would listen to a song and it wouldn’t be relegated to the background. Then it became tempo-oriented and more for dancing. The common hashish became ‘substance’. The unharmful discotheques became clubs,” he says, adding that today, the artistry of music is getting lost. “Today, you’re a singer or an instrumentalist; it’s not about the emotion or expression. It’s all been done before and there’s nothing new to say. If you don’t express yourself on stage, then you’re not an artist.” In 2020, a group of young musicians launched a compilation album Then & Now to celebrate Bose’s 50-year-long and illustrious career. “Seeing that there is still an interest in my music tells me that there is merit in music. I’m happy that at this stage of my life, I’ve done what I had to do. For 50 years, I made music about issues that mattered to me. I knew you couldn’t change the world overnight. I just tried to emphasise the ideology of peace and anti-war. That is my truth and it’s a concept that I live with every day of my life,” he concludes.

I knew you couldn’t change the world overnight. I just tried to emphasise the ideology of peace and anti-war, says Bose.[/caption] In his 50-year career, Bose has seen how the music industry has changed. “Before the idea of consumerism, music meant something. You would listen to a song and it wouldn’t be relegated to the background. Then it became tempo-oriented and more for dancing. The common hashish became ‘substance’. The unharmful discotheques became clubs,” he says, adding that today, the artistry of music is getting lost. “Today, you’re a singer or an instrumentalist; it’s not about the emotion or expression. It’s all been done before and there’s nothing new to say. If you don’t express yourself on stage, then you’re not an artist.” In 2020, a group of young musicians launched a compilation album Then & Now to celebrate Bose’s 50-year-long and illustrious career. “Seeing that there is still an interest in my music tells me that there is merit in music. I’m happy that at this stage of my life, I’ve done what I had to do. For 50 years, I made music about issues that mattered to me. I knew you couldn’t change the world overnight. I just tried to emphasise the ideology of peace and anti-war. That is my truth and it’s a concept that I live with every day of my life,” he concludes.

Rebel with a cause: Susmit Bose tells the story of his radical career, why he wrote anti-war songs advocating for peace

Rohini Kejriwal

• July 3, 2021, 13:01:07 IST

Susmit Bose’s music reflects the influence of Hindustani classical musicians, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan and the bauls. His album Train to Calcutta was the first original English one to have come out in India.

Advertisement

)

End of Article