In February 2016, I sat with 17 others to discuss what love meant. It was a college assignment, but we all took it pretty seriously, with the classical romanticism and arrogance of student-journalists who would soon be out in the real world harping about the big stuff. Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love — which we were instructed to read and discuss — had two married couples discussing love over gin. They talk at each other instead of to each other, and rely a little too much on the unsaid. As the gin runs out, so do the words tumbling out of their mouths. Anger and confusion over the evasiveness of love’s definition sail through their room as an unintentional but necessary piece of information, but it seems the characters cannot decipher it yet. We could not either. Carver’s prose was impressive — it was sparse and searing — but I could not wrap my head around the idea of love it was trying to project. Till that point, I thought of love as linear and sweet, every day moments from which lovers spun into cotton candy for the most part. My friend though, who knew more about almost everything than her peers, quipped at the end: “This should have been called What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Love.” Nearly four months after that class, I found myself swimming in a love which, pardon me for the excess, felt like someone had cracked the sun open and its warmth had spilled out into the sky. I got comfortably attached to the idea of love we have always been programmed to believe in: The idea of being relaxed, of being understood, of being happy. I had the love that was nearly as real on social media as it was in life. I felt victorious and was adamant to maintain it. But that is not what happened. In 2019, I felt loneliness creeping on me like a stranger forcing agonising conversations on loop. I always took love very seriously, and this was a gigantic blur. So I took Joan Didion’s advice — “In times of crisis, turn to literature, information is control” — and returned to Carver.

What began as a minor reflection of the spectacular institution that love and marriage are — at least that is how I thought of it back then — ended up being a grand reveal of all that was so magnificently broken.

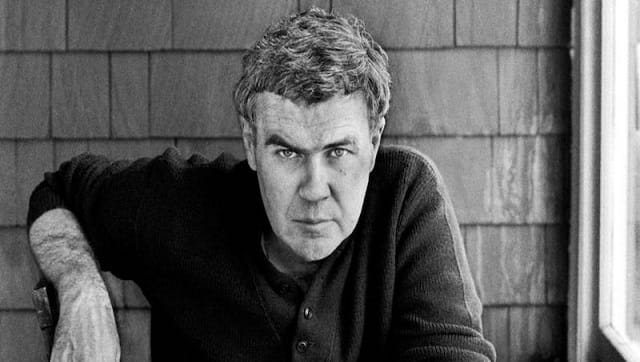

On the surface, nothing really happens in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, the titular story from the collection of short stories. Drinks are passed as the couples try to pin down what love is. Teri confronts she was beaten up and dragged by her ex-lover, and while that was most certainly abuse, she is convinced that was most certainly love too. Mel, Terri’s husband, does not agree. At one point, Mel and Laura, the wife of the narrator, share glances, indicating they share a mutual attraction. Mel does most of the talking; he is the one constantly reflecting on the transience of love: How each one of them loved before, how one of them grieved for a while but the other moved on and loved again. Love was there before too, sure. But where did it go? Can there be love when there is violence? As the sun and the gin go out, they stop talking. All their experiences and knowledge of love, all the intuition and aggression they had deployed, has come to naught. They are adults who think they know what they are talking about. But they do not. I was a little scared when I finally got this. There were no answers. What is the point even? I was still hopeful at this point, despite the dreariness of a certain reality I was gradually coming to terms with. What I had was indeed love, despite the emotional violence we inflicted on each other, I told myself. It wasn’t an illusion. But over time, as I kept moving to other stories, I witnessed the aftermath of ordinary relationships gone awry, perfectly revealed in silence and lack of understanding. The pattern repeated itself over and over again: Of lonely lovers tearing each other apart, drowning in alcohol, holding on to strangers for temporary respite, or staying put and marinating in their misery. In Everything Stuck to Him, Carver dwelled on the misfortune of a fragmented family. The lovers met when they were teenagers and had a daughter soon. In present, they have fallen apart. We do not know why things did not work out between them, but neither do they: "Things change, he says, I don’t know how they do. But they do without your realising or wanting them to be." [caption id=“attachment_10373071” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Raymond Carver[/caption] I re-read Gazebo in 2020. Duane has cheated on Holly, and is now trying to fix the mess. Their conversation is strained. Duane speaks with desperation, but what he says falls flat. Holly speaks with resignation: “Something’s died in me. It took a long time for it to do it, but it’s dead. Everything is dirt now.” No reasons are given for anything but it is evident that Holly’s finality did not stem only from that act of infidelity, but a slew of other disillusionments over the years. This was also when the finality of my truth dawned on me. I recognised immediately that we had been deteriorating for a long, long time. In the moment I let my guard down, I saw our manipulations, the deliberate hurting of each other, and the complacency of routine. In several moments of tenderness, our raw emotions burst open the lies. The process still took two years. But I would not call any of it unfortunate; we began and ended with our own chaos. In Carver’s words: “We had reached the end of something, and the thing was to find out where to start.” And then: “Things were going downhill very fast. We just did not have the heart for it anymore.” Rereading Carver feels like coming a full circle: With every visit, I observed that not only was I looking at something I could not believe I was looking at, but also entirely trusting it. To spend years reading and rereading Carver was to let Carver decide what love meant for me. In my case, like everyone else’s, the message was loud and clear: There is a downside to love, the grimmest being that it is probably unattainable. The one I loved and I — we watched our faith burn for nearly six years, the most youthful years of our lives. We felt so pressured for the longest time to emulate the perfect relationship that whenever we hit a wall, we analysed love when we should have analysed ourselves in love. We were Terri and Mel — the more we talked, the more we struggled. It was futile. We eventually became a part of the Carver universe; our jealousies, our rage, our insecurities, and misery — everything got to us, everything got the better of us. The shine was lost, the rapture replaced by regret. We built it first, and then destroyed it. It was gorgeous and devastating. “It’s impossible to keep love; you will certainly lose it to one thing or the other,” a friend said to me recently. We have experienced this get truer, fiercer. Carver, had he been alive today, would have probably mocked the car crash of the forevers and happily-ever-afters that partly run the social media show. From Carver, I learnt that love is not linear. We are made to believe time keeps moving forward, and everything is finetuned to the idea of progression. We tell ourselves that things can be different, but tomorrow will always be better. I have learnt that to think of love as linear at any point is to be further away from the last. Wherever we stand in the universe, in love, we may be the farthest from the centre. Anshika is a writer based in Delhi.

Raymond Carver[/caption] I re-read Gazebo in 2020. Duane has cheated on Holly, and is now trying to fix the mess. Their conversation is strained. Duane speaks with desperation, but what he says falls flat. Holly speaks with resignation: “Something’s died in me. It took a long time for it to do it, but it’s dead. Everything is dirt now.” No reasons are given for anything but it is evident that Holly’s finality did not stem only from that act of infidelity, but a slew of other disillusionments over the years. This was also when the finality of my truth dawned on me. I recognised immediately that we had been deteriorating for a long, long time. In the moment I let my guard down, I saw our manipulations, the deliberate hurting of each other, and the complacency of routine. In several moments of tenderness, our raw emotions burst open the lies. The process still took two years. But I would not call any of it unfortunate; we began and ended with our own chaos. In Carver’s words: “We had reached the end of something, and the thing was to find out where to start.” And then: “Things were going downhill very fast. We just did not have the heart for it anymore.” Rereading Carver feels like coming a full circle: With every visit, I observed that not only was I looking at something I could not believe I was looking at, but also entirely trusting it. To spend years reading and rereading Carver was to let Carver decide what love meant for me. In my case, like everyone else’s, the message was loud and clear: There is a downside to love, the grimmest being that it is probably unattainable. The one I loved and I — we watched our faith burn for nearly six years, the most youthful years of our lives. We felt so pressured for the longest time to emulate the perfect relationship that whenever we hit a wall, we analysed love when we should have analysed ourselves in love. We were Terri and Mel — the more we talked, the more we struggled. It was futile. We eventually became a part of the Carver universe; our jealousies, our rage, our insecurities, and misery — everything got to us, everything got the better of us. The shine was lost, the rapture replaced by regret. We built it first, and then destroyed it. It was gorgeous and devastating. “It’s impossible to keep love; you will certainly lose it to one thing or the other,” a friend said to me recently. We have experienced this get truer, fiercer. Carver, had he been alive today, would have probably mocked the car crash of the forevers and happily-ever-afters that partly run the social media show. From Carver, I learnt that love is not linear. We are made to believe time keeps moving forward, and everything is finetuned to the idea of progression. We tell ourselves that things can be different, but tomorrow will always be better. I have learnt that to think of love as linear at any point is to be further away from the last. Wherever we stand in the universe, in love, we may be the farthest from the centre. Anshika is a writer based in Delhi.

)