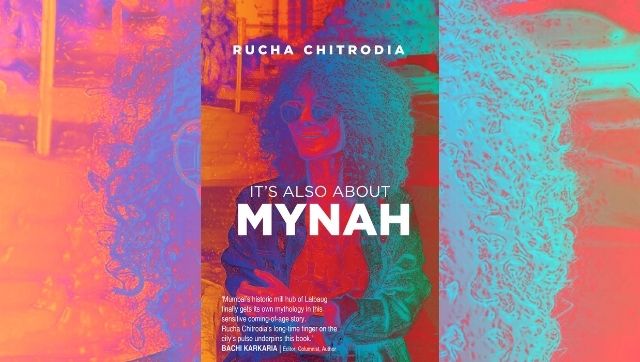

In her debut novel, author Rucha Chitrodia explores the innermost desires and complex emotions of a young woman finding her footing in a strange city, amidst new people and the prospect of an exciting new job. It’s Also About Mynah makes for an endearing coming-of-age narrative that unfolds through the eponymous Mynah’s experiences of living in the old mill district of the bustling Mumbai city and of the hard truths of ‘adulting’ that she must learn along the way. Filled with heartbreak and healing, professional crisis and personal grief, Chitrodia’s prose has all the elements that make up the life of a small town girl arriving in a big city, including a heartbreaker for a boyfriend, a lonely but caring landlady and most importantly, Mumbai itself, which welcomes every outsider into its colourful landscape. The excerpt that follows describes Mynah’s encounter with her admirer Rohit, and how she copes with her first heartbreak in the city. *** Umbrellas bloomed as Mynah began to climb the incline that led to her gated apartment complex but she didn’t reach for hers in the black tote. Bring it on, she muttered under her breath, and sprinted towards her apartment wing, past a blur of gulmohars, coconut palms, frangipanis and a gigantic banyan tree, its wide trunk wound in white thread by married women for their husbands’ health and longevity. She lurched breathless into the waiting elevator in C Wing of the complex in Lalbaug, a central district in Mumbai, Bombay or Bambai, as the island city is called by its people and visitors, and visitors who go on to become its people. Liftman Raja Jadhav—a person who could not further shrink nor age his underfed body—welcomed her in with a ‘good evening’. The pleasantry reached his eyes because Mynah’s T-shirt was clinging to her. The other person who had entered the elevator along with her looked intently at the screen ahead that flashed numbers of storeys crested in an ascending order, as if mesmerized by their progress. His studied indifference made Mynah, panting against the steel-bodied elevator wall, smile faintly in gratitude. The elevator dinged to a stop on the fourth floor and she got out, thanking the liftman out of habit and bidding a breezy ‘bye’ to the other man who wished her back with a startled smile. At least my umbrella is dry, thought Mynah as she looked for a towel in her room. She woke the next morning to heaviness and chill. The floor of her room in Aruna’s flat where she lived as a paying guest felt cold as she walked barefoot to the long mirror on the wardrobe and looked into her swollen eyes. She walked back to her bed and let herself fall into it with a thud. Aruna’s muffled voice rose from the drawing room. ‘Mynah, are you okay?’ ‘I’m running a temperature, aunty. Must be at least a hundred and four. No, a hundred and five. Remember, I got totally drenched yesterday? I am dying now.’ ‘Don’t die right away. Let me get you some ginger tea first.’ ‘That,’ said Mynah, ‘would be awesome.’ As Aruna tiptoed in, Mynah jumped up to give her a hug, unmindful of passing on germs, and fell into the bed back again, this time with Aruna, both giggling. Rohit, the fourteenth-floor resident of the fourteen-storey Jamuna Heights, was twitchy with anticipation as he entered the elevator the next morning. He willed it to stop on the fourth floor. It didn’t. Mynah reached home after work to a laid table. Aruna insisted she finish three chapatis with dal, a salad and a leafy vegetable first. After the feeding came the slaughter. ‘A cute man was here looking for a young girl who had dropped a book in the elevator while getting off on the fourth floor. He said he was guilty of keeping it with him for so long. Mynah, you have an admirer.’ ‘What book is it?’ asked Mynah, looking distractedly for the television remote. Her reaction was typical. Aruna laughed and got up to get it. ‘It is called, let me see, Resurrection at the Workplace.’ Mynah grimaced and gestured with her hands to imply why would she even hold such a book. ‘But he seems like a well-read fellow. This book is written by that famous psychiatrist, Dr Wu.’ ‘Shrinks find time to write books? That’s news to me, dude. I should write a book on what happened to his patients.’ Aruna grinned and ran a hand through Mynah’s curls. ‘Don’t you want to know anything about him?’ she asked tenderly. ‘Yes. I will have to give it back to him. Where does he live?’ asked Mynah, more than a little flattered. Rohit had wanted Mynah since his encounter with her breezy ‘bye’. He began to go up and down the two passenger elevators in their wing a couple of times a day and sat out free hours on a couch in the entrance lobby of the apartment wing pretending to read on his phone in the hope of bumping into the wet girl. On Day Six he got off on the fourth floor with the book and knocked on the door the girl had approached that evening. A woman opened it. He felt a surge and forgot reason. Her mouth, bosom, curvaceous frame, indifferently rolled up hair, arms akimbo, head a little tilted and knowing light eyes obliterated all else till she spoke. ‘Yes?’ asked Aruna, eyebrows raised, in a flat, matter-of-fact tone. Clearing his throat, he said, ‘I was looking for a girl who had dropped this book in the elevator about a week ago. I am guilty of keeping it with me for so long. I had seen her get in here. Is she around?’ Aruna looked at the boy and knew he was in the market and had put her in the shopping trolley as well. [caption id=“attachment_9499771” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  In her debut novel, Rucha Chitrodia writes an endearing narrative of a young woman adulting in a big city. Image via Facebook@RuchaChitrodia[/caption] ‘She’s not home but I’ll ask her about it when she returns,’ she said, trying to sound stern and succeeding. ‘What’s her name, please? Just in case,’ he asked, his throat dry. ‘Mynah. Where do you stay?’ ‘I’m on the fourteenth floor. Flat 1403. Mynah. That’s a lovely name. I’m Rohit.’ He held out his hand. Aruna did not offer hers. ‘I’ll tell her,’ she said, still unsmiling. ‘Thank you, ma’am. And what’s your name, please, if I may ask?’ He conjured up a silky smile. ‘Aruna aunty,’ she replied and pursed her lips. Rohit stiffened and left after bowing in an Oriental fashion, unconsciously copied from Hong Kong wuxia movies. Aruna had no desire to play the field and definitely not with Mynah’s suitor in this life or the next. Rohit was beautiful. His eyes were a dark brown, lips pink and thin and dipping in all the right places, nose straight and adequate, and skin translucent. His cheeks shone like rubies in Mumbai’s all-weather humidity. Robust women fell for his dainty appeal at sight. The more feminine capitulated soon upon finding a man who spoke their language and who was willing to share his torturous life story with them rather than act collected and male. He spoke easily of his father’s struggles as a professor who plodded till he saved enough to open his own coaching school. He expounded the family’s move to a flat in leafy Kalina, the eastern counterpart of the western suburb of Santacruz, closer to the city centre than their former one in what he called mofussil Dahisar up north. The move was a happy result of success, after flyers of Professor Trivedi’s Coaching Class in Borivali, also up north, began to be distributed along with morning newspapers, and students who aimed to graduate with jaw dropping scores lined up at the 800-square-foot commercial space he had rented to teach. Rohit often underscored his mother’s sacrifice in bringing them up with limited cash and without a maid or a husband available to help her. Some women would pat his hand at that and feel tenderness well up inside them. ‘I had to chip in with housework and sweep and swab the floor whenever she was unwell, even during exams. Mohit, my brother, was the baby of the house, so we never asked him to do anything. But it’s no big deal.’ He would dole out the line with a self-effacing smile. A rope trick that made him climb right up women’s estimation of him. *** ‘So what’s the problem, ma?’ Dr Murali Radhakrishnan was seated in a window-less cabin in the farthest corner of his packed clinic in the city’s southern Fort locality, named after a fortified structure built during the reign of the East India Company. Mynah and her guardians—Aruna and part-time help Susheela—were in no mood to admire the worn-out colonial buildings. They had gotten off the taxi an hour ago and killed time in the doctor’s waiting room. Right in the middle of the large waiting room, bordered by benches for patients, hung a majestic swing with ornate silver prongs fastened on to a wooden slab on its two sides. The significance of the swing was not obvious to visitors such as Aruna who had never met Dr Radhakrishnan before but had read his opinion on mental health issues in newspapers and had therefore sought him out for Mynah. Dr Radhakrishnan told his juniors the swing, which moved like a pendulum under a large fan, was intended to lull his patients into a more receptive frame of mind. The doctor looked at the young woman with southern curls, milk chocolate skin and abnormally large and unusual yellow eyes. Her nose curved delicately towards her full brown lips. ‘He just left me like that and does not take my calls,’ Dr Radhakrishnan heard Mynah tell him. ‘Then stop calling him,’ replied the doctor simply. ‘We are so close that I never have to think before picking up the phone. I just call. But why doesn’t he pick up? He must have seen my thousand missed calls. What has changed? My father did not like him but what does that have to do with us?’ she presented her perplexity without expression. This moved the doctor who had never managed to not get moved by young women. Stage one, he thought. Mynah turned her golden eyes to the floor and kept playing with her fingers, clenching and unclenching them to an inaudible rhythm. She spoke after a period of silence since Dr Radhakrishnan had responded to her laments with his. He wanted to hear her out. ‘I want to hear his voice. Why shut me out like this? Overnight. Everything changed in that one meeting. Everything. It’s all turned topsy-turvy.’ The doctor wanted to smile as he had not heard the usage in a long time. It took him back to his school when a teacher, Sujata ma’am, had made him repeat it ten times as he had mouthed ‘tospy-turvy’. He was eight then, a plump boy his mother considered too thin and insisted on feeding five meals a day. He hated food for years because of it but missed the attention now that he had come to depend on a walking stick. Reluctantly, he returned to Mynah, her little world and her regular problem. ‘Okay, ma, give me his number. I’ll call him.’ ‘You will? Do psychiatrists call people? Is it allowed? He does not even know that I have been taken to one. Aruna aunty recommended you and so we are here. Just for consultation. Otherwise I would have been sleeping in my room. I feel like sleeping all the time and hope when I wake up things are back to normal. But when I wake up, I remember they are not. It all comes back in a rush and I feel like sleeping again to forget that he does not want to speak to me anymore. Does it not pain him that he has not spoken to me for three days? Is three an unlucky number? Maybe he’ll pick up the phone tomorrow.’ ‘What are you feeling right now?’ ‘I don’t feel anything, to be honest. I just want to hold him and not feel sleepy. I know I’ll be alright then. But what if he does not want to speak to me ever?’ ‘You can sleep as much as you want, ma. Don’t expect answers just yet. Forget about it all for a day.’ Dr Radhakrishnan was also a hypnotist. He met Mynah’s eyes and made contact with her through the haze. She nodded and went out for a psychometric test for which she was made to look at triangles and squares and blots of colourful ink, asked to describe them and then to write down stuff about herself, her thoughts, her dreams, her nightmares, her past, her expectations. No one had ever wanted to know her this well. If she were whole, she would have laughed at this inordinately high amount of interest in her. *** The above excerpt from Rucha Chitrodia’s It’s All About Mynah has been reproduced here with permission from Amaryllis

It’s Also About Mynah is a coming-of-age narrative that unfolds through the eponymous Mynah’s experiences of living in the old mill district of Mumbai and of the hard truths about ‘adulting’ that she must learn along the way.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)