India’s relations with Nepal have always been a bit of a curiosity for scholars. For two countries that share so much, culturally speaking, they really should be much closer than they are (the same could be said for Pakistan, you would argue, but let us not go there). Instead, every couple of years, we have a new flashpoint (even seemingly frivolous things like the Hrithik Roshan Nepal controversy) in India-Nepal relations, and we are reminded of just how fraught things continue to be.

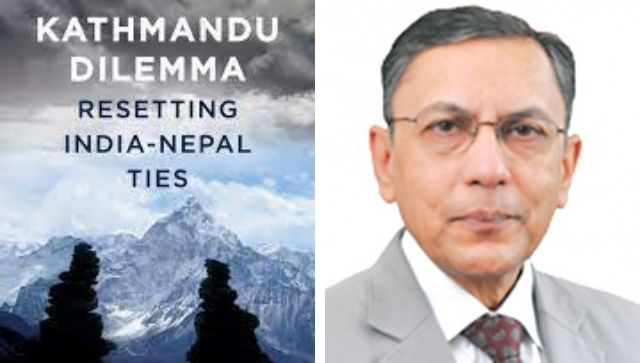

Ranji Rae, former Indian ambassador to Nepal, also headed the Northern Division in the Ministry of External Affairs (dealing with Nepal and Bhutan) from 2002 to 2006. In his recently published book Kathmandu Dilemma: Resetting India-Nepal Ties, Rae draws from his own experiences to examine decades of India-Nepal ties — the high and low points, as well as what India can do better moving forward.

As Rae writes in the introductory chapter, “Ours is perhaps the most intimate and hence complex relationship that exists between any two neighbouring countries. Everything that binds us — religion, culture, traditions, language, ties of kinship — also creates tension. Even the famous religious sankalp or pledge that every Hindu takes before a puja, refers to Nepal as being part of Bharatkhand! If everything in Nepal is similar to that in India, then what is it that makes Nepal a unique nation-state? Nepalese sometimes resent cultural commonalities, especially when referred to by Indians; harping on these can become counterproductive.”

Ranjit Rae spoke to Firtspost during a telephonic interview earlier this month. The following are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Right at the beginning of the book, you talk about meeting Prime Minister Narendra Modi, so my first question to you is simple: what are the changes that you have noticed in India-Nepal relations since 2014, when this government came into power?

Nepal has been undergoing a major political transformation, and if you look at its contemporary history, it’s been a struggle for multiple transitions; for political emancipation and a more inclusive society. Finally, these changes were codified in the new constitution in 2015. These transitions include moving from a monarchical system to a republic, from a unitary system to a federal one, from a Hindu rashtra to a secular republic. Now these are very fundamental changes, and so obviously, they have had a huge impact on India-Nepal relations.

As far as the current Indian government is concerned, India, under its Neighbourhood First Policy, has always backed Nepal, and sought good relations with all its neighbours. When two countries have as intimate a bond as between India and Nepal, some friction is expected from time to time. But I dare say that there are no issues between these two countries that cannot be resolved through talks.

You have written about how Parmanand Jha, a former Vice President of Nepal, decided to take his oath in Hindi (this oath was later declared void by the Supreme Court of Nepal), reflecting his identity as a Madhesi from the Terai region. The Madhesis, who form a third of the population of Nepal, have close familial and cultural connections with the people of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Could you tell us a bit more about their place in Nepali politics?

Nepal is a very diverse society. One-third of the population are the Madhesis, another one-third the hill janjatis, and one-third the ruling Pahadi elites — Brahmins and Chhetris. Historically, it’s these elite castes that have ruled Nepalese society. Now, in post-Independence India, and especially since multi-party democracy entered Nepal, there is a greater awareness about the issues of disadvantaged groups. The Madhesis and the hill Janjatis want greater say in political affairs. They wanted their share of economic resources. Clearly, these demands had to be accommodated in some way, because otherwise the country would have continued to be in turmoil. This was India’s point of view too: that in a country as diverse as Nepal, if the interests of all groups are not accommodated there would be turmoil, and that would present an opportunity to forces inimical to both Nepal and India.

One of the many Nepali politicians you talk about in the book is Rambaran Yadav, who happened to be educated in Calcutta, and he went on to become Nepal’s first president in 2008. There are so many Nepali politicians like Yadav who went to college in India, who have other familial and cultural connections to India. And yet, down the years, there has been a fair bit of patronising of Nepal and Nepalis at the hands of Indians, right?

That’s true, and this is something I have said before: we are a little bit insular when it comes to our neighbours. For most elite Indians, the only Nepalis they know are either Nepali elites, or the many Nepalis who are working in menial jobs across the country. So naturally, in this limited interaction, they form an image inside their heads that may be considered patronising.

As for Nepali students, today they continue to come to India, some of them. But there are many who go to Australia, to China, to other countries as well. At the political level, what needs to happen is that there should be engagement between the MPs of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, and their Nepali counterparts. Because the kind of interpersonal relationships these lawmakers of their respective countries had in the past between themselves, it’s no longer there, I am sorry to say. We need to know much more about each other at all levels, and especially between the young people of the two nations.

One of the most fascinating sections in your book talks about how Indian companies like Dabur were extremely successful in Nepal through the 1990s, after the reforms in the Indian economy. However, you also strike a cautionary tone here when you point out that over the last five to 10 years, it has been China that tops the list for most new investments. Two questions here: One, how is it that we never see success stories like Dabur’s in Indian pop culture (which, by and large, only focuses on the India-Nepal border as a smuggling route, eg the 2020 film Yaara )? And Two, by ’new investments,’ do you mean that Chinese companies are big in the retail sector in Nepal? Well, as far as popular Indian representations of Nepal are concerned, it’s really unfortunate that we continue to produce these stereotypical stories around this beautiful, diverse country. I think that education about our neighbours is necessary among not just Indian creators but the public in general.

Now, coming to the China question, there have been new investments by Chinese companies in the retail sector, yes. But there has been so much more. China has made sizeable investments in cement, too, for example. Two airport contracts in Nepal have been awarded to Chinese firms. India, too, is in the picture. We invested in some hydro-electric projects in Nepal, but that was a government undertaking. It’s the private sector where Indian companies are lagging behind in terms of new investments. We need to figure out why this is the case when in the past, Indian companies like Dabur (they still make their Real Juice in Nepal, and sell it across India, a system that works well for them), ITC, and Tata etc have done so well in Nepal.

Towards the end of the book, you write about a number of Hindu pilgrimage sites in Nepal, like Janakpur. You also mention that a number of these pilgrimage sites appear to have fallen into disrepair. Why is it that despite the amount of time and attention paid to Hindu and Sikh pilgrimage sites in Pakistan, for example, a similar issue in Nepal is largely ignored?

It’s surprising, and I should point out that there’s immense potential for developing sites of Hindu pilgrimage in Nepal. It’s not just Janakpur. There’s also Muktinath, there’s Pashupatinath in Kathmandu. There have been talks about developing a circuit of Ramayan tourism in Nepal, connecting Ayodhya with Janakpur and certain other sites. We’ve been talking about developing a similar thing with Buddhist sites as well, about connecting Lumbini (the birthplace of the Buddha, now in Nepal) with Sarnath and other Indian Buddhist destinations.

I am not satisfied at the pace at which these developments are taking place, but some things are happening. We need to develop pilgrimage tourism between India and Nepal; not only is this something that will benefit both countries but even at the individual level, it’s something that will generate a lot of goodwill amongst the people of both India and Nepal.

Kathmandu Dilemma: Resetting India-Nepal Ties is published by Penguin Random House India.

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

)