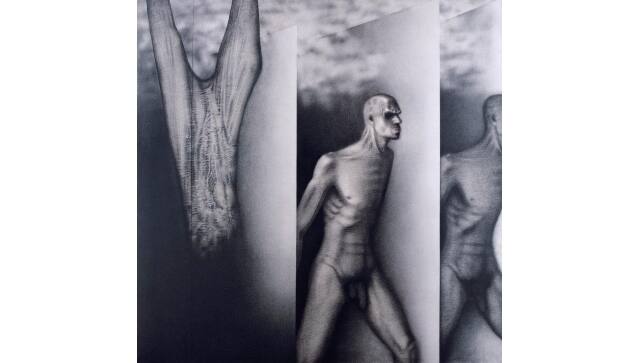

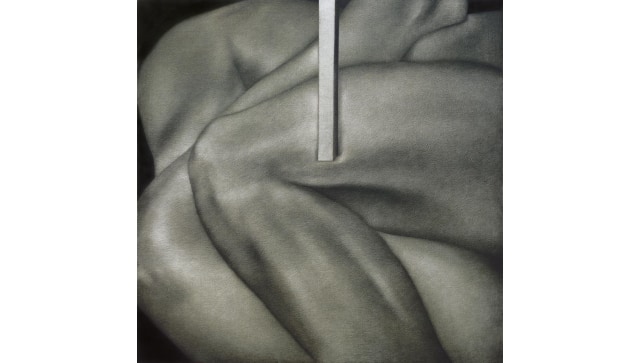

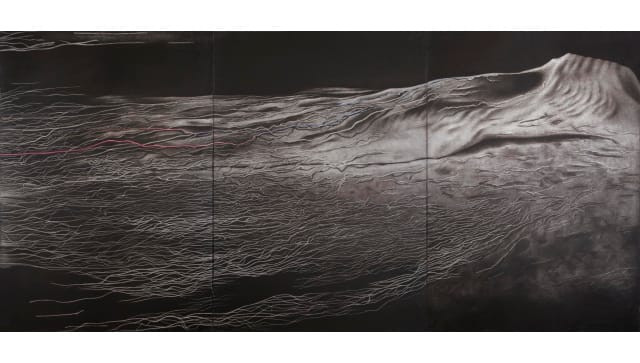

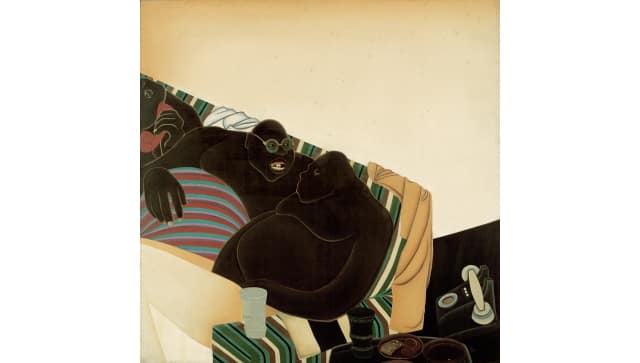

When Kiran Nadar made one of her first purchases as an art collector in 1998, her husband Shiv, in her own words, was “horrified”. Being the founder of IT major HCL Technologies who went on to become one of India’s richest men, the price of the painting, by well-known painter Rameshwar Broota (b 1941), was the least of his concerns. It was the subject matter of the painting that bothered him. The painting, a 1982 oil-on-canvas titled Runners, depicted two muscular men in the nude. It appeared that one of the bald, ghostly forms had had his eyes gouged out, revealing him in a state of immeasurable despair. Adjacent to these unheroic-looking men, was a carcass, hung upside down, recalling the sight of slaughterhouses selling meat. The form of the carcass seemed to blur the distinction between an animal and human. “How can we have the painting of a male nude in the house? We’ve got a young daughter, and my mother lives with us,” Shiv told his wife. Kiran Nadar, the founder and chairperson of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, recollected this anecdote in an interview published by KNMA. The painting, part of a 2014 retrospective at the museum, finally made it to their collection, once Shiv viewed it in person at the artist’s studio at New Delhi’s Triveni Kala Sangam, which he joined as the head of department in 1967. [caption id=“attachment_8635681” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Rameshwar Broota, Runners, 1982, Oil on canvas, Collection KNMA[/caption] If the Nadars were convinced about the intensity of the painting then, viewing the same work now, nearly forty years after it was made, conveys a different meaning. The tormented men, along with a butchered body, reflect the paranoias and struggles of our times, when the body needs constant attention, care and protection from the deadly coronavirus. It is in the context of a terrifying global scenario that the museum has revisited one of its past shows, Visions of Interiority - Interrogating the Male Body: Rameshwar Broota - A Retrospective (1963 - 2013). Glimpses from the exhibition are available on the museum’s website, in the form of a virtual walkthrough of Broota’s paintings, along with press clippings on his work, short films made by the artist, and a recording of his interview. Roobina Karode, KNMA’s director and chief curator, situates the practice of Broota, who is known for his sustained exploration of the body and its vulnerabilities, in the present times: “Life at present is gripped by the fear of mortality and death, pain and helplessness, fighting an invisible enemy. The KNMA team felt it was pertinent to re-present the retrospective that would bring to the audiences, the overbearing emphasis in Broota on the human body and its predicament.” [caption id=“attachment_8635701” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Rameshwar Broota, Absorbed, 2001, Oil on canvas, Collection Private[/caption] Broota was born into an artistically inclined family. His parents had a flair for singing, he recalled in an interview. His brothers, who later pursued teaching in psychology and philosophy, drew and painted with a great deal of imagination and likeness to their subjects. “They had a natural command over art. They should have been artists, instead of me,” he said in an interview with Chandigarh Lalit Kala Akademi. As a schoolboy, he was inspired by a fellow student who could draw the figure of Krishna on the class blackboard, with the help of a chalk. Excited about this new discovery, Broota went back home and tried to create the same figure on the walls of his house. After failing miserably at getting the forms right, he drew his human figures with the help of a bowl that he placed on the wall. Soon, he began drawing and using watercolours on his own. His early gravitation towards developing and honing the perfect form continues to shape his practice even today. It predates his graduate studies in fine arts, which began in the 1960s at the Delhi College of Art, and where the training in anatomy cemented his career-long engagement with the human form. It is an engagement that is deeply tied to his own understanding of beauty, even though his visual language does not adhere to conventional ideas of beauty. “My sense of beauty is more about the structure, and not about it being smooth, lyrical, or beautiful. Instead of being beautiful, aesthetics are a must in the painting,” he said in the Lalit Kala Akademi interview. [caption id=“attachment_8635711” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Rameshwar Broota, Metamorphosis VI, 1986, Oil on canvas, Collection KNMA[/caption] In Broota, who has been painting for the last five to six decades, the body acquires many forms, primarily as the man and the ape. One of his earliest works in the exhibition, from 1963, is an oil-on-canvas portrait of himself, which is rendered in a realist style taught in art schools. Staring at no one in particular, the image of a contemplative and lost young man anticipates the mood of his later works, such as the paintings showing emaciated labourers and migrant workers. Later, these melancholic sights would metamorphose into the form of the omnipresent image of a bald, naked, solitary man, who looks increasingly dehumanised. It is a form that has been a defining feature of Broota’s practice. This primal looking predatory man, whose body and face are bereft of human characteristics and features, could be capable of gory violence, Broota suggests in his paintings. And yet, in all the canvases, he appears to be the victim of his own making, lost in a self-created trap. [caption id=“attachment_8635721” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Rameshwar Broota, His Silence Keeps a Vigil, 2004, Oil on canvas, Collection Private[/caption] In his other paintings, Broota introduces elements from the urban and automated life, by showing the invasion of technologies and architectural forms in our life, as if they are slowly attacking the very core of our being. Metal scaffoldings, sharp objects, robotic masks either surround or pierce Broota’s men. From showing the so-called civilised looking man in his 1963 painting to an increasingly distorted being, with a few paintings only showing some of the body parts, the painter’s theme is that of man’s fall from grace. The dramatic luminous effect in his monochromatic paintings is achieved through a simple technique, which is both laborious and time-consuming. It involves scraping away at the canvas with a knife or blade, after applying multiple layers of paint over it. The result is two-fold. His forms appear sculptural, where the bones or veins stand out sharply, with a distinct tactile feel. The powerful textural nature of some of these paintings loosely recalls the art of etching, a printmaking technique in which lines are etched onto a metal plate, using a sharp tool. There is no respite or escape from Broota’s grim world, not least when he depicts, in vibrant colours, the caricaturised images of bloated apes as a corrupt class of politicians and bureaucrats. The artist’s satirical lens shows them in multiple avatars: huddled up on a garish sofa as if scheming against a competitor; or wearing sunglasses, and carrying files under their arms, beaming with mock self-importance. In the latter, they wear only pyjamas and a set of polka-dot bras. [caption id=“attachment_8635691” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Rameshwar Broota, Untold Story, 1976, Oil on canvas. Collection Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi[/caption] Women or children are conspicuous by their absence in Broota’s paintings, which depict a cloyingly monolithic world, where even the animals appear extremely masculine. It is a question that has often been posed to Broota in interviews. To this, he said: “I didn’t make a female figure because I wasn’t sure if I would have been able to make it or not. And I didn’t want to move towards beauty. Being a man, I have gone through so much struggle, maybe I am closer to the male figure.” But a key takeaway from this retrospective is not the omnipresence of man, but his gradual disappearance. The paintings from the 1980s onwards show the man in traces, with a faint outline of his face and body. In some other works, such as the Traces of Man series, he has been removed completely from the picture plane. Where the man is obliterated, different forms of nature, like a tree or a mountain, betray a sense of ferocity, while creating an atmosphere of an incoming cataclysmic event. In others, indecipherable lettering, reminiscent of an ancient hieroglyph, and fossilised forms replace the man, suggesting a bygone era. Is Broota imagining a world without humans? Are we going to start our history all over again? He makes us ponder over these imaginary possibilities at a time when we face our own moment of reckoning with a world that is already looking very different from what we have known until now. All images courtesy of Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

The tormented men, along with a butchered body, reflect the paranoias and struggles of our times, when the body needs constant attention, care and protection from the deadly coronavirus

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)