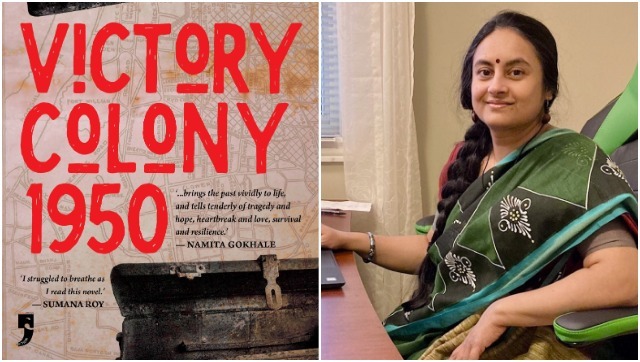

Bhaswati Ghosh’s debut novel Victory Colony 1950, published by Yoda Press, is an absorbing book about the lives of refugees from East Pakistan who learn to trust their own instincts and the camaraderie of friendly strangers when the Partition of India in 1947 forces them to show up in Calcutta. Ghosh refuses to let her characters drown in their grief. Amidst squalor, malnutrition and poverty, they begin to repair and rebuild. They do not want to live off government handouts. Ghosh’s story centers the experience of Amala Manna, a woman who is not only displaced from home but also separated from her younger brother. At the refugee camp, she makes new friends and also finds love. Manas Dutta, a volunteer who assists in relief and rehabilitation efforts, surprises her with a marriage proposal. While he is intensely committed, his mother disapproves of their relationship. The novel explores how they deal with this challenge together. Edited excerpts from an interview with the author, who lives in Ontario, Canada. How did you work on keeping your novel free of the clichés that haunt Partition writing? While the Partition as a historical event does form the backdrop of the story, my main concern was what happens to Amala, the central female character after the fact. I wanted to step into her world to see what all someone who has just experienced extreme trauma must go through — first to survive and then, to redeem hope off an essentially hopeless situation. In doing so, I found her world expanding, with the inclusion of other ill-fated people like her, and strangely enough, the story that emerged out of this association wasn’t all bleak and hopeless but one of new families being formed and love springing in the most unexpected of ways. Would you tell us about your personal connection with the subject of Partition, since your own grandparents were also refugees from East Pakistan? What were their lives like? In what way did their stories help you craft this novel? I grew up in Delhi in the late 1970s and 1980s and, for a long time, the history of my family’s loss in Partition didn’t come upon the screen of my consciousness in any direct way. Ours was a joint family — my mother came to live with her parents after her divorce, on the heels of my birth. My maternal grandmother, Amiya Sen, who was also a published author in Bengali, piqued my childhood imagination with stories of her village in East Bengal — of its verdant lushness and riverine beauty, of its fruit orchards and freshwater ponds full of fish, of an abundance that seemed to be in striking dissonance with our lower-middle-class reality. It was only as I grew up that the apparition of Partition — invisible yet ever present in those stories — became apparent to me. So, growing up I saw how the displacement had affected not only my grandparents — the direct victims of it — emotionally and financially, but how it continued to leave its stamp on the successive generations — my mother’s and uncle’s, and then my brother’s and mine. My family story didn’t directly aid me in writing this novel, but it had a huge indirect, subconscious impact. That influence, coupled with my reading of my grandmother’s short stories, many of them dealing with this inalienable part of her personal and family history, prepared me to write Amala’s story. Incidentally, Amala happens to belong to Barisal in East Bengal (now Bangladesh), the district my grandparents came from, and one that saw widespread communal violence in 1949-50, the period of this novel. “It had become clear to Manas that the state administration didn’t have a solid plan to tackle the worsening refugee situation. Nor did the central government for that matter.” When I read this sentence in the book, I wondered if it might be as relevant today as it was right after the Partition. What do you think about the treatment of refugees by the West Bengal administration and the Government of India? Across the world, human displacement remains as pressing a concern today as it was in the years following the Indian Partition. It may not always grab the headlines, but that doesn’t discount its presence. Whether it is about Rohingyas in the Indian subcontinent, African refugees desperately looking to enter Europe, or refugees from war-ravaged countries like Syria, the stories of people like Amala continue to come to us through different news mediums. Given the frequency of these news items and the sheer volume of people involved, these stories barely register in our consciousness before we’re benumbed to them again. To answer the second part of your question, when it came to refugees from the East, both the West Bengal state government and the central government in India were found wanting in dealing with the situation. This became evident to me during my research, through both anecdotal as well as documented records. I felt it was important to include in my narrative. Language plays an important role in shaping public perception about refugees in India where you grew up, and in Canada where you live now. Could you please describe the thought process that went into your representation of refugees, the depiction of the refugee camp, and the police brutality experienced by refugees? It is unfortunate how tragedy, when it strikes a large number of people at once, renders them into a nameless mass with generic labels such as refugees or migrants. It’s almost as if they are instantly coalesced into a monolith and no longer remain individual lives in distress. Along with this comes the stripping of their dignity. Through Amala and the other refugee characters in the novel, I wanted to bring the focus back on how such mass tragedies affect the life of one person or one family. What does it mean to them on a day to day basis? How deep are the scars over the long term? I hoped to do this in their own voices, using their language — sparse and utilitarian perhaps, but not lacking in warmth or affection. On the other end of the novel’s character spectrum are the government officials and people like Manas’s mother who represent the mindset with which such destitute groups of people are often viewed by the majority of the populace — condescension and disgust, sometimes to the point of intolerance. Again, such a mindset of majoritarian entitlement wasn’t limited to that time period; we can see it manifest even in our current world. Amala seems to have the inner resources to look after herself. She is creative, enterprising, and resilient. What made you give her a happily ever after with Manas, a man who is physically and emotionally drawn to her but also appears to fancy himself in the role of a benefactor and caretaker? I will answer the second part of your question first — the part where you talk about Manas being a benefactor/caretaker of the refugees, and by extension, of Amala’s. This question was crucial to me in writing this story. In the novel, Manas confronts this very topic in a long discussion with Chitra Sen, his senior co-volunteer. While Manas does come from a well-off family, he’s conscious of that privilege and its concomitant weight or burden. It was important to me to know that he wasn’t drawn to Amala impelled by a messiah/saviour impulse. But that rather he felt attracted to her because of the sheer force of her personality and her inner spirit, regardless of her circumstances. Remember, he might have been affluent and an activist, but he was also a young man with a beating heart. As for Amala, you’re correct in assessing that she had no real need of a happily-ever-after with Manas or with anyone for that matter. And she was certainly not looking for anything like that. But as it turned out, not unlike many other random happenings in her young life, love burst forth and she found herself pulled into its current. This might sound cloying, but this lack of personal control over a lot that happens in our lives — good or ugly — informed my storytelling. I do not mean to say that the love story appears forced. There are some beautiful moments in their rather unusual courtship but getting married imposes new shackles on Amala, whose mother-in-law Mrinmoyee views her as ‘shudra’ and ‘Bangaal’ rather than her son’s beloved. Could you please unpack the caste and language politics at play here, given the period this novel is set in? I wanted to explore what happens when a woman like Amala steps inside the world of someone like Manas whose stature is entirely different in terms of class and caste. Mrinmoyee’s attitude towards her isn’t atypical; in fact, such attitudes continue to prevail even now as is evident from the tragic outcomes many inter-caste marriages conclude in. For Manas’ Bhadralok (elite, upper caste) mother, the scandal of her son marrying a Bangaal (a term used to refer to the people of East Bengal, as opposed to the Ghotis of West Bengal) girl was exacerbated by the fact of her being a shudra, the lowest rung of the Hindu varna system. At the time the story is set in, the word Bangaal was used almost as an invective to deride Bengalis from the East, many of them refugees. Caste and class were important to me, particularly because of how entrenched these were in people’s minds during the period the story is set in, but also because of how forceful they continue to be in determining the course of relationships even in the 21st century. Focusing on these aspects was also a way to allow the reader to test Manas’ love for Amala. Early in the novel, he claims to remain steadfast in his commitment to her, even if that means going against his family. In the time following their wedding, while he does try his best to change his mother’s outlook, he also makes it clear to her that he wouldn’t be one to cower down in submission or worse, become indifferent and passive to the situation. Since the book is about Hindu refugees from East Pakistan, which is now Bangladesh, do you wonder how it might be received by people who stand for and against India’s Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2019? How do you grapple with the need to memorialise the brutalities of the past without playing into the agenda of those who want to create divides today? Human history moves in cyclical patterns, and what has happened before has every chance of recurring again, even if some of the visible elements acquire a different appearance. This is crucial to note, for the differences are mostly surface level, whereas the underlying pattern remains as sinister as ever. As Amala’s story shows, while those in power, and I don’t mean political power alone, make sweeping decisions on behalf of large sections of the population, the impact — sometimes devastating — is borne by those who wield little power. In this context, markers like religion or ethnicity have scant significance as the overarching determinant is power and who has it at any given point in time in history. Amala and folks like her suffered because they were on the wrong side of this power divide and worse still, minorities. The need to remember the brutalities of the past is important, even necessary, precisely because of this reason — so that we can draw lessons from them and avoid repeating such violent histories. The novel took me back to your essay Bhasha, Basha, Bari published in 2011. Towards the end, you mull over the definition of home and ask, “Is it a place? Or is it more likely a language?” If the novel is anything to go by, home is food, home is sisterhood, and home is generosity when it is least expected. Any concluding thoughts? You’ve summed it up so well. Home is all of those ideas and more. As I understand it, the very definition of home is dependent on the past and our memories of a time or place we no longer inhabit. Even in our attempts to “set up” home in newer geographies and time periods, we’re guided by those memorised signposts and the comfort of their familiarity. Hence, the need to recreate mother’s food, establish sisterhood anew or paying forward the kindness your neighbour of the majority community had once shown to protect you from the wrath of their own. Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, educator and researcher. He tweets @chintan_connect

Bhaswati Ghosh’s debut novel Victory Colony 1950 is based on the lives of refugees from East Pakistan.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)