Below are edited excerpts from an interview with Nishad Avari, Christie’s [New York] Specialist, Head of Sale and Associate Vice President, South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, on famed painter Jehangir Sabavala.

Can you give a detailed insight into the period from when Christie’s began auctioning the works of Jehangir Sabavala?

Christie’s first sold Sabavala’s work in 1995 as part of one of the first dedicated international auctions of Contemporary Indian Art in London. Since then, Christie’s has offered his work for sale regularly in our auctions of South Asian Modern and Contemporary art. Jehangir Sabavala is one of the modern Indian artists whose work has been regularly featured in our auctions since the category was established.

You mentioned that Sabavala has achieved record prices at your previous two auctions. When were these two auctions staged, what were the estimate prices at the two auctions, and how much did the prices finally climb to?

In 2021, Sabavala’s painting titled The Embarkation sold for $1,590,000, significantly surpassing its estimate of $300,000 – 500,000, and eclipsing the previous global auction record for the artist’s work also set at Christie’s in 2020. The earlier record was set by his painting titled The Peasants, which sold for $966,000 in September 2020. The estimate for that work was $450,000 – 600,000. Prior to the sale of these two paintings, Christie’s achieved a record for the artist in 2015 in Mumbai, where Sabavala’s The Casuarina Line sold for Rs 48,225,000 [approximately $721,630]. This painting held the record for six years, until it was surpassed by The Peasants.

Can you describe these paintings in some detail?

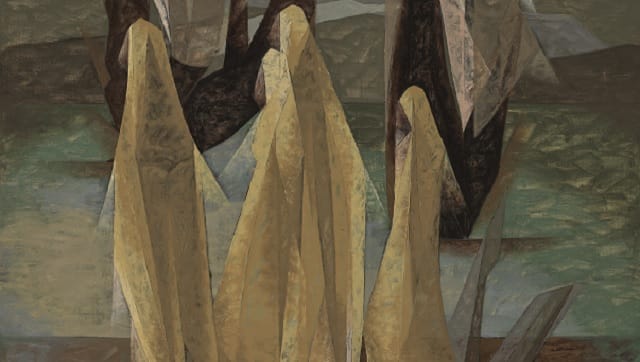

Both The Embarkation and The Peasants epitomise a key moment in Sabavala’s career – his middle period, from the 1960s to the 1980s, when his work was characterised by the quintessential Neo-Cubist style he developed, a muted color palette, and imagery related to both physical and spiritual journeys. These paintings contrast with the saturated, bold colours of his early paintings, and are also notable for their heavy emphasis on the figure, unlike the largely unpopulated landscapes that characterised much of Sabavala’s oeuvre.

In The Embarkation, painted in 1965, Sabavala portrays a captivating scene where four wraith-like figures clad in long yellow robes prepare to board two ships anchored in the waters beyond them. The figures lack the heaviness and solidity of the figures in his earlier paintings. Instead, they are rendered subtle and ethereal, detail eluded in favour of the fluttering of fabric that implies the outline of a body.

[caption id=“attachment_10373731” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The Peasants[/caption]

The title of the painting evokes the sense of anticipation before these wanderers board their ships, as they turn towards unknown lands. The ships resemble Viking long ships, evoking Norse myths related to passage into the after life. Indeed, Sabavala himself has talked about the spiritual qualities of his wanderers, as they perennially struggle towards the promise of heaven. The background of the composition consists of the murky, choppy sea and dark, subtly gradated mountains that loom above the central figures.

Though The Peasants was painted 16 years later, it contains similar themes to The Embarkation, in its depiction of itinerant subjects in the midst of a spiritual journey. This painting also features a group of itinerants, and similarly explores the artist’s fascination with cloaking, veiling, and other forms of wrapping the body. While in earlier paintings, Sabavala’s figures are small and distant, lost in his great landscapes, in these two works, the compositions are anchored around the figures, who take up most of the frame, suggesting perhaps their agency as they set out on their journey.

In The Peasants, Sabavala synthesises his unique visual language with a favoured subject matter from his early period – everyday Indian people, particularly those he encountered while travelling throughout the country in the 1950s. Sabavala has described the subjects of The Peasants as rugged Maharashtrians, a tough group ready to weather any challenges their environment presents. They are well-prepared as they hold walking sticks, and wear thick brown shawls, clearly about to set out on a difficult journey. Far ahead of them, at the foothills of the hazy blue mountains in the distance, lies a group of houses, either a rest stop for the night or their elusive destination.

What do you feel are the various factors which are triggering Sabavala’s prices to record levels?

There are several factors that have contributed to an increasing demand for Sabavala’s work. The most important is the growing scarcity of paintings by the artist. As museums and institutions acquire his work, fewer return for sale to the secondary market. Additionally, the Indian art market as a whole has been growing from strength to strength, as more collectors develop an interest in modern Indian art and enter the market, and as more institutions begin to acquire works in this genre. Significant works by several modern Indian artists now draw a great deal of interest from collectors around the world, which in turn leads to higher prices at auctions.

Furthermore, Sabavala was one of the few modern Indian artists to extensively document his oeuvre, and several books on his work have been published over the years. This has made his work more accessible to collectors around the world, who are eager to learn about modern art from South Asia.

Additionally, as a very articulate and social artist, Sabavala was always willing to discuss his paintings and creative process, building up interest in his work and a dedicated network of collectors around the world during his lifetime.

Were Sabavala’s prices going below expectations at earlier Christie’s auctions? If so, what would you identify are the major reasons for them going below anticipated levels? Were his paintings underestimated by bidders?

Works by Sabavala have consistently exceeded their estimated auction values at Christie’s, dating back to the 1990s, when they were first offered for sale. In recent years, his paintings frequently soar above their high estimates. For example, at Christie’s auction in Mumbai in 2015, a painting by Sabavala was sold for over Rs 4.8 crore, and another work on paper achieved Rs 27.5 lakhs, far exceeding their estimates of Rs 1.2 to 1.8 crores, and Rs 8 to 12 lakhs respectively.

Do you see Sabavala’s prices climbing further in future Christie’s auctions? If so, what will be the critical reasons for his paintings to escalate further and create waves?

As great works by modern Indian artists become harder to source, prices at auction will likely continue to climb. We hope that the collector base for Sabavala’s work will continue to grow as the modern Indian art market expands.

How would you view Sabavala’s paintings against the Progressive Group of artists?

It is difficult to compare an individual with the Progressive Artists’ Group, given the short-lived and somewhat fluid nature of the collective, which was not defined by any singular style or aim. The participating members did not have a singular vision for modern Indian art, but instead explored Indian art in a variety of ways. Sabavala was a perennial outsider, never belonging to a group or collective, though his approach to the questions of modern Indian art has certain parallels to the experiments of his peers.

It is important, however, to note that Sabavala experienced a decidedly different Bombay [now Mumbai] than many of his artist peers. Most of the members of the Progressive Artists’ Group came from very modest backgrounds, and had little money when they started off on their careers. All of them struggled in their early days, identifying with the working class and urban poor, something reflected in the Groups’ early association with the Communist Party of India, and often in the content of their paintings.

In contrast, Sabavala’s background allowed him to study art in multiple countries, and cultivate a global collector base. He was less interested in the political dimensions of modernism, instead retaining a fascination with the aesthetic and technical aspects of making art. Though he felt closely connected to the Indian landscape and culture, he continuously re-evaluated and advanced his craft, ignoring groups and trends that rose and fell through the course of his career.

[caption id=“attachment_10373711” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The Casuarina Line II[/caption]

Will Christie’s focus more Sabavala’s paintings at future auctions, and field more of his works?

We would be very happy to feature more paintings by Sabavala at auction, but it does depend on the availability of his work, which is increasingly rare. Sometimes, we do discover paintings that were previously unknown or unseen. The Embarkation was a thrilling discovery that became a highlight of the4 2021 Asian Art Week auctions in New York.

Can you please delineate a detailed background of Sabavala’s life and work?

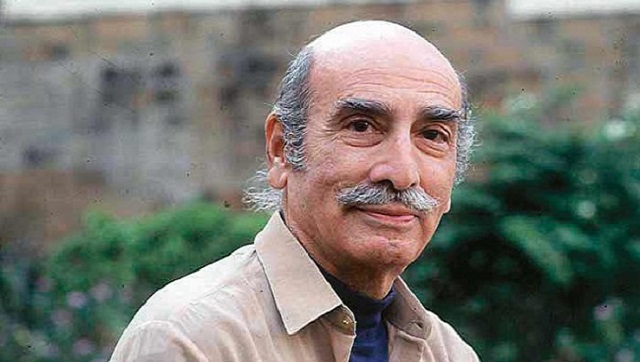

Jehangir Sabavala was born in 1922 into an aristocratic Parsi family. Throughout his childhood, his family travelled frequently, exploring India, Europe, Asia, North America, and Australia. His mother was a great lover of theatre and the arts, and took him to museums and galleries around the world, exposing him to a multitude of influences from a young age.

While Sabavala initially sought to attend Oxford, he was forced to return home in 1941 at the outset of World War II, and instead attended college in India. In Bombay, he studied at Elphinstone College, though he did take some classes at the Sir JJ School of Art. When the war ended in 1945, he decided to return to Britain, with the intention to study acting.

However, soon after arriving in Britain, he decided to continue his visual art studies instead. He studied at the Heatherly School of Art in London from 1945 to 1947, where he met his wife Shirin Dastur, whom he married in 1948. After London, Sabavala moved to Paris, where he studied for four more years, like other Indian artists of his generation, including Syed Haider Raza, Akbar Padamsee, and Ram Kumar. Here, he studied Cubism under Andre Lhote, a key influence on his work. The artist returned to India in 1951, though he would continue to travel back and forth between Europe and India for another decade, before finally settling in Bombay in 1959.

[caption id=“attachment_10373811” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The Embarkation[/caption]

Throughout the 1950s, Sabavala advocated for the burgeoning contemporary art scene in Bombay, lending his support to local critics and galleries. He also continued to experiment, transitioning away from his early work to a decidedly unique Cubist style, characterised by rich, eye-catching colours, bold lines, and a mix of spiritual imagery and quotidian scenes of life in India. In the late 1950s, Sabavala started to move away from the overt influence of Cubism, instead creating softer, more contemplative paintings. This change was solidified by the death of Andre Lhote, and his introduction to art critic Charles Fabri, who challenged him to develop his own style rather than continue to emulate Cubism.

In this period, Sabavala began anchoring his paintings around small groups of figures in vast landscapes, with a relatively muted palette. The distance between subject and viewer, combined with increasingly somber palette, created a sense of mystery that Sabavala would strive for in the next few decades.

Sabavala also started painting his famed wanderers – the hooded figures, peasants, monks, and nuns – against unidentifiable landscapes, forever in transit to an elusive destination. Sabavala has often been compared to a monk himself, due to his disciplined, solitary career, and careful, methodical style of painting. He would spend extensive amounts of time preparing, investigating the subtleties of light and colour in his natural subjects to determine the dozens of hues he might use in a painting. His fascination with wanderers also may reflect his cultural background as a member of the Parsi community, who left Persia to live as a minority in India.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Sabavala continued to build on these advances in his development of a distinct style, turning his focus primarily towards landscapes. His landscapes became increasingly abstract and , taking on a hazy, dreamlike quality. Sabavala also turned upward and began creating views of the sky, his clusters of wanderers replaced by clusters of birds mid-flight. In this era, Sabavala sought to express the vastness of nature, and create a grandiose sense of scale within the confines of a canvas.

Throughout his career, Sabavala steadfastly refused to cater to any particular ideology or political concern, though he always cared deeply about the opinions of those who viewed his work. The artist continued to paint until the last year of his life, endlessly re-evaluating and improving upon his craft. His last solo exhibition was held at Sakshi Gallery, Mumbai, in 2008, and his archive and last paintings are now part of the collection of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalay in Mumbai.

Throughout his life, Sabavala received considerable acclaim for his work. In addition to exhibiting around the world, he was a recipient of the Padma Shri from the Government of India, the Lalit Kala Ratna from the President of India, and is the subject of two documentary films. He passed away in 2011.

Ashoke Nag is a veteran writer on art and culture with a special interest in legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)