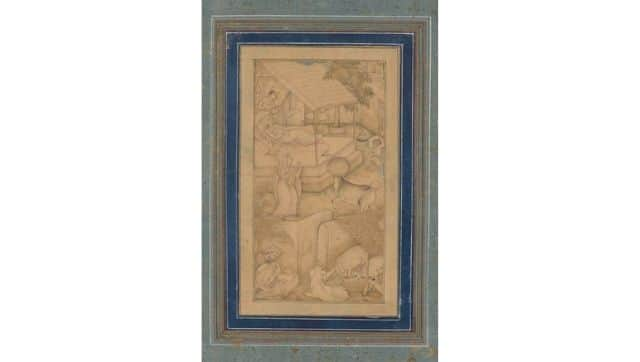

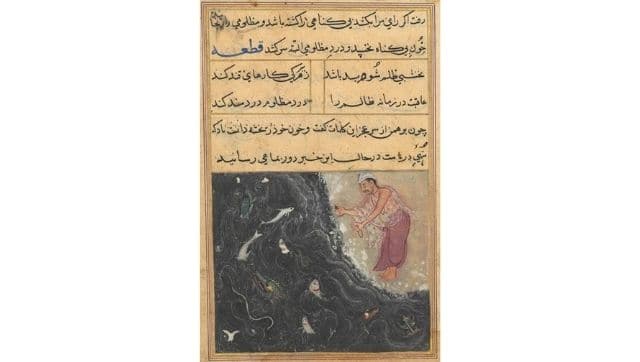

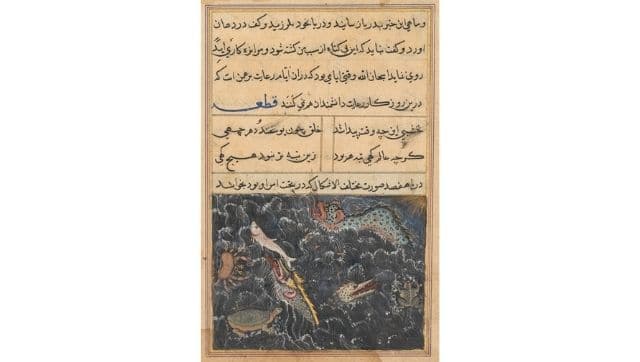

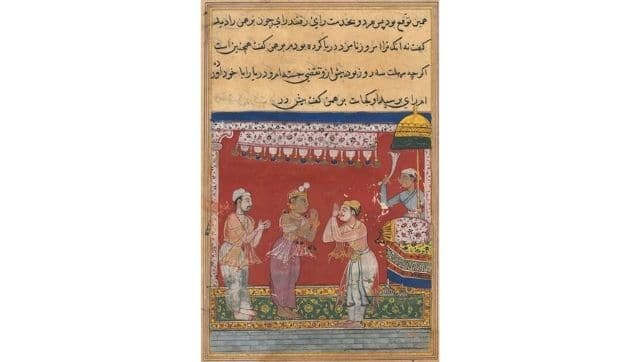

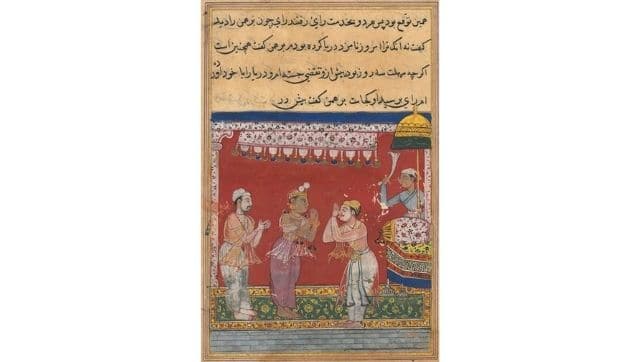

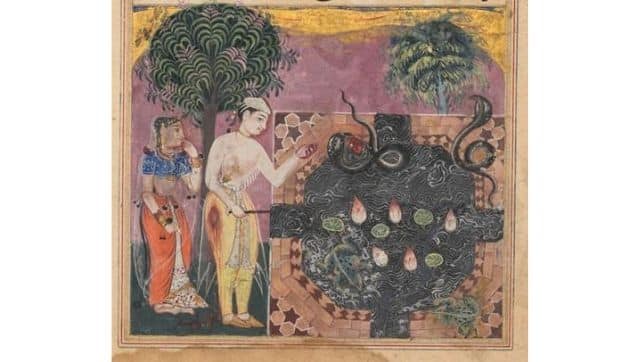

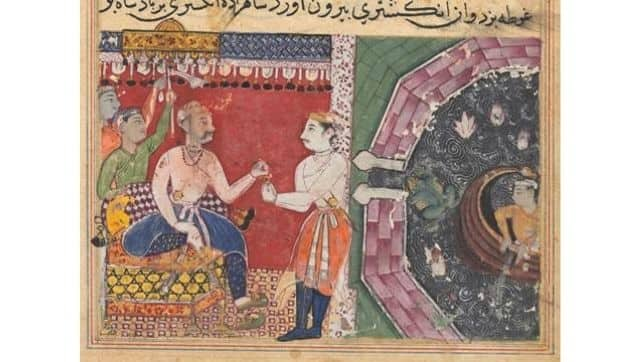

Moralistic and entertaining, animal fables have been popular in India for thousands of years. Particularly during the 700s to 1400s, Indian tales travelled with merchants and scholars to the Arabian Peninsula and Iran, and made their way back again, sometimes slightly altered or organised into a different weave. Tuti-nama or Tales of a Parrot has fascinated storytellers, historians and researchers for centuries owing to its rich history and artistic style. Firstpost speaks to the Cleveland Museum of Art in whose collection survives an early manuscript of the Tuti-nama and decodes the stories this rich collection has to offer. Animal fables of India The Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot) is a literary work written in 1329–30 in Persian by the learned Sufi author Ziya’ al-Din Nakhshabi (d. 1350). The paintings of the Tuti-nama depict scenes from the 52 stories told on successive nights by a pet parrot to beguile Khujasta, the wife of his owner, through the night so that she would be too enthralled to leave home to meet her lover and succumb to an adulterous affair. [caption id=“attachment_9816311” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  A woman mistakes a cow for the Angel of Death, from a Lights of Canopus (Anwar-i Suhaili) of Kashifi (Iranian, d. 1504), c. 1610. Mughal India, reign of Jahangir. Gum tempera on paper; painting: 19.7 x 10.2 cm (7 3/4 x 4 in.); framed: 38.1 x 26.7 cm (15 x 10 1/2 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Michael Silver and Deborah Lader in memory of Rabbi Daniel Jeremy Silver 2019.81[/caption] Many of the paintings depict the parrot addressing Khujasta, as well as a scene from the story in which Khujasta kills the mynah bird who beseeches her to stay home and remain faithful to her husband. The stories include animal fables and tales of clever women who accomplish their goals by means of their wits or their virtue. A rare copy of the Tuti-nama survives in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art that was calligraphed and painted in the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar (r.1556-1605). One of the most important manuscripts in the history of Indian painting, it appears to have been commissioned by the young Akbar shortly after his accession to the throne at the age of 13. The richly detailed images are accompanied with calligraphy written in the Arabic script known as naskh. It is also an exemplary instance of the fascination Mughal emperors had with art, calligraphy and their interest in the world around them. [caption id=“attachment_9816331” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The Brahman’s predicament is conveyed by the wind to the fish who carries the news to the king of the Ocean, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eleventh Night, c. 1560. India, Mughal, Reign of Akbar, 16th century. Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 x 14 cm (8 x 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 8.3 x 10.2 cm (3 1/4 x 4 in.) The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.89.a[/caption] The provenance of the manuscript Sonya Rhie Mace, the Cleveland Museum of Art’s George P Bickford Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art explains that the Cleveland Tuti-nama appears to have been painted by at least 45 different Indian artists in the imperial Mughal workshop (kitab khana) headed by the Persian artists Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd-al Samad. She states, “Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd-al Samad were two of seven Persian artists Akbar’s father Humayun invited to India from Tabriz in Iran. Only 10 or 12 of the artists are identified by name; there seem to be two different artists named Banavari and two named Tara.” Over the course of his rulership, Akbar hired hundreds of artists from across northern India to join his atelier under the direction of the Persian artists and create a copious output of paintings. The paintings in the Cleveland Tuti-nama are among the earliest surviving works by Indian artists in Akbar’s atelier. [caption id=“attachment_9816341” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The creatures of the sea are asked by the king of the Ocean to take a message to the Brahman, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eleventh Night, c. 1560. India, Mughal, Reign of Akbar, 16th century. Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 x 14 cm (8 x 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 7.3 x 10.1 cm (2 7/8 x 4 in.) The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.89.b[/caption] The Cleveland Museum of Art purchased a nearly complete, illustrated, 16th-century manuscript of the Tuti-nama in 1962 from the Bernard Brown Agency in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The manuscript once consisted of 341 folios; 13 are either missing or in other collections. It had been unbound and the pages separated by Bernard Brown, who was selling the paintings individually, until Sherman Lee, director of the Cleveland Museum of Art from 1958–1983, purchased the entire manuscript and bought back as many pages as possible. Written and painted on a thin paper of a light ivory colour, the pages in the manuscript have been re-margined, probably during the 19th century when it was rebound. A second version of the Tuti-nama was made for Akbar during the early 1580s, a large segment of which is in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin; the remaining pages are dispersed among numerous collections. The Cleveland Tuti-nama appears to be earlier in date, as the paintings reveal the pre-Mughal styles of the various artists and the process of formation and assimilation into what would become the early Mughal painting style. The Chester Beatty Library Tuti-nama is illustrated with paintings that are much more consistent and confident in their fully Mughal style. [caption id=“attachment_9816351” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The king of the Ocean, having assumed human form, arrives at the court of the Raja, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eleventh Night, c. 1560. Ghulam ‘Ali (Indian, active 1550s-1590s). Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20 x 14.7 cm (7 7/8 x 5 13/16 in.); painting only: 11.5 x 10.3 cm (4 1/2 x 4 1/16 in.) The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.92.a[/caption] The styles and themes of the Tuti-nama The style of the paintings has been thoroughly analysed by Pramod Chandra in his Tuti-nama of the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Origins of Mughal Painting in 1976. He showed that artists coming from three main styles prevalent in northern India before the reign of Akbar contributed to the creation of the Tuti-nama, while working to assimilate Persian features that Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd-al Samad encouraged. The colours are lavish and wide ranging, with many layers of expensive, mainly mineral pigments used for most of its 224 paintings. Four different white pigments, two different blues, two different greens, mercury-based red, arsenic-based yellow, and abundant use of gold and silver are present. Frequent instances of overpainting and reworking can be discerned on close inspection of many of the works. As Pramod Chandra wrote: “These constant struggles and attempts…make the study of the Tuti-nama an extremely fascinating and human one, placing us in a position from where we can, as it were, watch the creation of the Mughal style over the shoulders of the artists themselves.” (Chandra 1976, pp. 165–66) Apart from the style, these folios give us a peek into the India of the time: its jewellery costumes and traditions. Mace adds, “The paintings depict the figures in both Indian and Mughal dress, often with a full complement of jewellery. They depict a range of Hindu and Islamic religious practices, settings, ceremonies, and holy men and women, being a true amalgam of Indian religious life.” [caption id=“attachment_9816361” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  From Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eleventh Night, c. 1560. India, Mughal, Reign of Akbar, 16th century Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 x 14 cm (8 x 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 10.4 x 10.1 cm (4 1/8 x 4 in.) The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.93.b[/caption] They also reveal a wide geographical range of international awareness, with protagonists from far-flung regions such as eastern Africa, Afghanistan, Iraq, and China; the stories are set as far east as the borderlands with Burma and as far west as the “land of the Israelites.” Style of painting Some of the artists of the Cleveland Tuti-nama worked in a style seen in many Indian manuscripts produced throughout northern, western, eastern, and central India of the 15th to early 16th century, which favoured primary colours, bold black outlining, pert gestures, strict profile, and a relentless two dimensionality of space relegated into horizontal registers. Mace states, “Other artists were working in one of several hybrid styles inspired in part by Persian paintings in their pastel hues and delicate decorative sensibilities. The tastes of Akbar himself, judging from his other commissions, was for dynamic action, spatial depth, and lifelike forms.” All of these stylistic elements are to be found in a range of combinations and concentrations throughout this manuscript that resolve, with the addition of some inspiration from European paintings and prints, into a new painting style that comes to be known as the Mughal style. [caption id=“attachment_9816371” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The prince, having deprived the snake of its natural food, a frog, feeds it with a piece of his own flesh, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eighteenth Night, c. 1560. India, Mughal, Reign of Akbar, 16th century. Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.132.b[/caption] Relevance today The paintings were commissioned by one of India’s most celebrated rulers whose ecumenical ideals can be seen in this work made during his adolescence. Even during the 14th century, when the text was written, Hindu and Muslim, Indian and Persian cultural elements merge seamlessly throughout the tales, and this cultural merging would have appealed to Akbar. In his own court, Islamic Mughals from Central Asia intermarried with Hindu Rajputs from Rajasthan, and multiple languages of Turkic Chagatai were spoken alongside Hindi, Arabic, and Persian. [caption id=“attachment_9816381” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The prince, with the help of Mukhlis who changes into a frog, recovers the ring lost in the sea, and returns it to the king, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eighteenth Night, c. 1560. India, Mughal, Reign of Akbar, 16th century. Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.135.b[/caption] Mace adds, “Also, it appears that Akbar had a learning disability; he was unable to read or write with ease, but he loved pictures and recitations. He was able to participate in the erudite literary court culture of the Persianate world by asking Indian and Persian artists to paint thousands of narrative scenes, histories, and portraits throughout his reign.”

The paintings of the Tuti-nama depict scenes from the 52 stories told on successive nights by a pet parrot to beguile Khujasta, the wife of his owner, through the night so that she would be too enthralled to leave home to meet her lover and succumb to an adulterous affair.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)