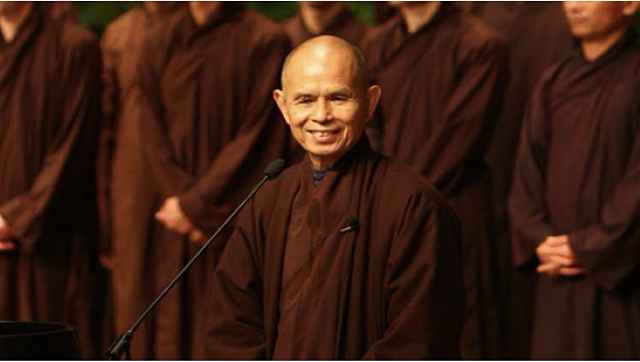

Thich Nhat Hanh, the poet-monk-activist who passed away on 22 January, led a life so rich in compassion that every book of his feels less like a sermon, more like a piece of his heart. He is widely acknowledged as the founder of “Engaged Buddhism,” a term that he coined during the war in Vietnam in the 1960s to bring home the understanding that meditation ought to be motivated by a strong desire to do something to relieve suffering – in you, and around you. Two months before his passing, a team of disciples from Plum Village – the monastery that he established in France – published a book called Zen and The Art of Saving the Planet with Rider Books. They put together selections from his teachings, interspersed with commentary. It is a marvellous piece of work, introducing readers to a lifetime of the Zen master’s teachings on mindfulness, interbeing, love, resistance, non-violence, ethics, and courage. Thay, as he is fondly addressed by people from all over the world, speaks about the origins of Engaged Buddhism in this book. He shows that spiritual practice is not about disengaging from others; on the contrary, it is about being fully present in a way that is most beneficial. He says, “To meditate is to be aware of what is going on, and what was going on at that time was suffering and the destruction of life… We had to find a way to practise mindful breathing and do walking meditation while helping those wounded by the bombs – because if you don’t maintain a spiritual practice during the time you serve, you will lose yourself and you will burn out… We learned to breathe, to walk, to release the tension so we could keep going.” What he describes here is the path of the Bodhisattva, one who practises on behalf of all sentient beings. The one who has woken up from ignorance and delusion is filled with boundless compassion. The Bodhisattva sees only sentient beings – not allies and enemies –and uses skillful means to connect with people regardless of the ideology they identify with. People who are unfamiliar with Thay’s life might dismiss these teachings as hot air since taking sides is much easier than finding common ground, and self-righteousness certainly brings instant gratification. Thay points out the irony of peace movements being led by people whose minds are filled with anger, hatred, and vengefulness. He says, “If you are an activist, and you’re eager to do something, you should begin with yourself and your own mind.” In this book, he recalls the fear, anger, and fanaticism that were widespread during the Vietnam War. Brothers were killing brothers because their minds were clouded by enmity. Communists wanted to destroy anti-communists, and vice-versa. He says, “The two blocs were being supported by international armies, money, and weapons. Each side was convinced that their view was the best kind of view, and they were ready to die for their view.” [caption id=“attachment_10323781” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Thich Nhat Hanh[/caption] Advocating for peace was a risky enterprise for people like Thay who did not want a war. He wrote anti-war poetry, and distributed peace literature. Such activities were officially banned at that time, and these people could be arrested. They had to carry on their work secretly. He says, “When you take a side, at least you’re protected by one side. But if you don’t take sides, you’re exposed to destruction by both, and so it’s very difficult. And in those conditions, we struggled for peace, and engaged in social work in the spirit of non-violence and non-discrimination.” Both sides saw him as a threat. He was forced to live in exile.

This book presents glimpses of how painful it was for Thay to be away from Vietnam. In doing so, it humanises a spiritual figure who might otherwise seem far removed from the concerns of ordinary folks caught up in the drama of life and its unceasing ups and downs.

When he left Vietnam in 1966 to call for peace, he planned to be away for only three months. However, things turned out differently. He says, “All my friends were in Vietnam; my work was there. Everything I wanted to do, and everyone I wanted to be with, were in Vietnam. But I was exiled for daring to call for peace. And it was very difficult.” He longed to go home. Back then, he identified home with a physical place. This changed dramatically over time. He says, “I tried to train myself to see that Europe was beautiful too; the trees, the rivers, and the sky there were all also beautiful… Over time, the sorrow and longing deep in my consciousness had been embraced by concentration and insight.” The desire to be in Vietnam was still there but he did not experience it as suffering. He made peace with being okay if he could never go back. Eventually, he returned to this homeland, and spent his last days there. It took him several years to arrive at this understanding: “The Vietnam War was a bad thing, and being in exile for 30 years was a bad thing, but because of that, I have been able to share the practice of mindfulness in the West. Because of that, we have Plum Village Practice Center in southwest France, and many other practice centers and communities of mindful living in Europe and the US.” He uses the analogy of mud that produces lotus blooms. At the same time, he does not fetishise suffering for he knows that too much mud can be harmful. It can overwhelm and destroy. The takeaway here is that nirvana is not to be sought outside of samsara. It is samsara, in fact, that provides a fertile ground, for awakening. We have a chance to use all our experiences as the field of spiritual practice. Mindfulness is not to be reserved only for the meditation cushion. We can be mindful wherever we are. This book reiterates the idea that happiness cannot be found by creating walls between ourselves and others, hoping that we can practice in peace by keeping all annoyance at bay. We must look into ourselves deeply to understand why we are so agitated, and what we can do to gift ourselves the peace and calm that we deserve. It will not come from outside. I love how he articulates the idea of interbeing or dependent arising, which is central to Buddhist philosophy. He says, “The notion of a separate self is like a tunnel that you keep going into. When you practice meditation, you can see that there is the breathing but no breather can be found anywhere; there is the sitting but no sitter can be found anywhere. When you see that, the tunnel will vanish, and there will be a lot of space, a lot of freedom.” Thay wants us to notice how this flawed sense of separateness that makes us harm not only human beings but also other species. We think of the earth in terms of natural resources that can be used to our advantage, rather than thinking of how deeply we are connected to it. [caption id=“attachment_10323811” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Thich Nhat Hanh[/caption] Buddhist teachers often emphasise how precious human life is, and how rare it is to get a human birth. I appreciate Thay for deflating the human ego bloating with this perceived superiority. He compels us to see that human beings cannot exist without non-human elements such as minerals, plants, animals, water, wind, fire, soil, sunlight, and the sky. He says, “We arrived very late, yet we behave as if we’re the boss here. We believe ourselves to be exceptional. We think we have a right over everything else and every other species, as though they have been created for us. With this view, we have done a lot of damage to the Earth. We want safety, prosperity, and happiness only for humans, at the expense of everything else.” We are because of others. We inter-are. This is his core teaching. According to him, non-violence is not a strategy, skill or tactic. It is way of life for people who cultivate compassion for all. He believes that being dogmatic about non-violence is not an intelligent approach. We should try to be as non-violent as we can but we should not impose absolutes on others. His approach to vegetarianism is grounded in this belief. He urges people to follow a vegetarian diet if they can without judging those who do not. He says, “You should not talk too much about it but simply invite others to enjoy delicious vegetarian dishes with you. There will always be people who continue to eat meat or drink a lot of alcohol, but we need 50 percent of humanity to volunteer to create balance… As others see your peace, joy, and tolerance, they will begin to appreciate a non-violent way of eating.” This is a great example of what it means for a spiritual practitioner to use skillful means while dealing with matters that are charged with emotion and opinion. The ease and the acceptance that Thay embodied through his teachings will continue to inspire me in the years to come. Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist, and book reviewer.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)