Heisnam Sabitri is a stalwart of Manipuri theatre with an impressive body of work that includes acting credits in plays like Nupi Thiba (1966), Tamna Lai (1972), Pebet (1975), Laigi Machasinga (1978), Memoirs of Africa (1986), Rashomon (1987), Migi Sharang (1991), Karna (1997), Draupadi (2000), Dakghar (2006), and Shadowing the Wild Woman (2011), among others. All of these were directed by her husband and creative collaborator Heisnam Kanhailal. Together, they founded the theatre group Kalakshetra Manipur in 1969. Sabitri has played a variety of roles in plays based on poems, folk tales, essays, and film scripts. She has also conducted theatre workshops with Kanhailal in India and elsewhere. Apart from this, Sabitri has acted in a Madhusree Dutta’s film titled Scribbles on Akka (1999), which revolves around the 12th-century Kannada saint poet Akka Mahadevi.

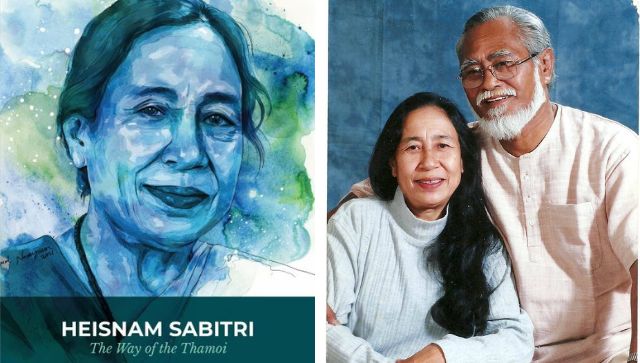

If you are keen to familiarise yourself with Sabitri’s contributions and achievements, read HS Shivaprakash and Usham Rojio’s book Heisnam Sabitri: The Way of the Thamoi. It will help you appreciate why this “critically acclaimed stage actor” was awarded the Padma Shri in 2008.

The most informative and insightful part of this book is a long interview with Sabitri conducted by the authors. It will give you an opportunity to encounter Sabitri in all her spontaneity and complexity but in translation from her mother tongue Meiteilon into English. Sabitri recalls that Kanhailal used to tell her, “If you want to be an actor, open all the doors of your heart. There are many layers which block our heart. You must open it all. Don’t speak from your throat, speak from your heart. Only then, you can communicate effectively with the audience.” His “creative manifesto” was “thamoi hangdoklaga angang oina sannou (open your heart and play like a child)”. Kanhailal, who passed away in 2016, was the one who urged Shivaprakash and Rojio to write this book but he did not live long enough to see it. Shivaprakash, a playwright, poet, novelist and critic, does not speak Meiteilon. Rojio does. He has known Shivaprakash and Sabitri for many years. In fact, Rojio was Shivaprakash’s student at the Jawaharlal Nehru University’s School of Arts and Aesthetics. Rojio is now a playwright, theatre director, and teacher. The book has been published by Niyogi Books. Sabitri, who is 76 as of today, married Kanhailal in 1962. Her journey in the theatre did not begin with him but with her aunt – theatre actor Gouramani Devi. Sabitri started working as a child artiste when she was seven or eight years old. She dropped out of school during “fifth class” after she began touring with her aunt’s theatre group that was rooted in the Vaishnava tradition. In the book, she says, “We would go from mandap to mandap, performing Gourangga Mahaprabhu during the kang festival (rath yatra). I played the role of Prabhu Nimai Sanyas. My aunt, my first guru, gave me the basic training on how to play the role.” Why did Sabitri transition from religious to political themes in her work? Was it a complete break, or merely a shift in emphasis? What role did Kanhailal play in her growth as an actor? How did Sabitri benefit from opportunities to perform in Malaysia, Japan, Egypt, and Indonesia? To what extent does she draw on rituals, mythology, and martial arts in her performances? The book engages thoughtfully with these questions, and provides answers. Shivaprakash and Rojio write, “In Sabitri-Kanhailal’s theatre praxis, the body is only one of the links in the chain of the body-breath-spirit continuum, which is the bedrock of the pantheistic worldview of tribal societies, including the Meitei tradition.” The authors believe that Sabitri and Kanhailal’s “theatre of the earth” cannot be fully understood without looking at its “philosophical ramifications”. It stands out for “arousing rasa in the hearts of the spectator-participants” and has “little to do with the materialist outlook of body-centred performance theories, which many theatre academicians invoke ad nauseam these days”. This book will be useful if you want to learn about Indian theatre beyond what is produced in cities such as Delhi, Bangalore, Pune, Mumbai and Kolkata. Shivaprakash and Rojio approach Sabitri with curiosity and humility, trying to make sense of her art on its own terms but also using their scholarly training to make connections and comparisons with the work of other theatre practitioners such as Ratan Thiyam, Habib Tanvir, Badal Sircar, Utpal Dutt, B.V. Karanth, Tadashi Suzuki, Bertolt Brecht, Jacques Copeau, and Antonin Artaud. They also discuss the influence of Mahasweta Devi and Akira Kurosawa on Sabitri’s work. The book points out that Kanhailal and Sabitri’s theatre emerged as a rejection of the Eurocentric theatre that came to India “under the misnomer of international modernism”. When they were offered a travel fellowship and asked to choose between Asia and America, they opted for Asia. They noted “striking resemblances” between Meitei and Indonesian rituals and theatre traditions. They also travelled extensively in Tripura, Meghalaya, and Assam “to discover continuities among Northeastern cultures without erasing particularisms”. Has Sabitri’s relationship to her theatre practice changed after Kanhailal passed away? How does she look back at everything that they created together? What gave her the courage and confidence to act in nude scenes? How did she navigate the discrimination that she faced as a woman? Read this book to find out. Shivaprakash and Rojio have done an excellent job in documenting the work of a person who deserves to be known more widely in Indian society. Chintan Girish Modi is a journalist, commentator, and book reviewer.

)