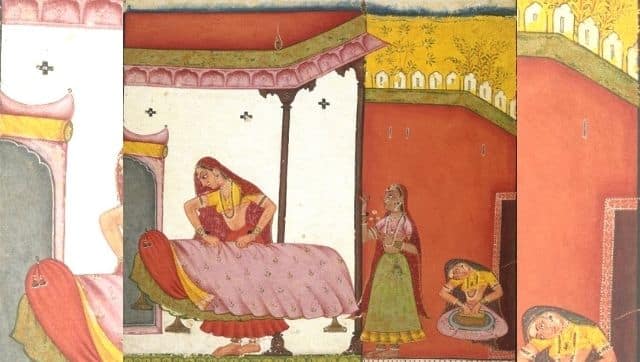

A nayika delights, saddens, bewitches, angers. In many ways, she provides catharsis, because her unabashed narration of her story – her woes, apprehensions and joys – evokes those emotions of love and desire within ourselves, whose existence we perhaps knew not of. In his Natyashastra_, written circa 200 BC, Bharat Muni expounded his theories on the practice and performance of theatre and dance in 36 chapters. It was within these verses that he crafted the ashtanayika, or the eight heroines based on eight different episodes from a woman’s life. The ashtanayika give voice to the thoughts of a woman caught in myriad situations concerning her lover, and are considered to be among the most beautiful and enduring forms of abhinaya in the study of Indian classical dance._ For centuries, each one of these instances has signified much more than the depiction of a woman’s conundrums and perils: they have come to denote her liberty to express herself, and her love — physical and spiritual — for her beloved. This is perhaps one of the reasons the concept of the nayikas has been nurtured through time, evolving with the world around it, while staying rooted to its essence. For a nayika is one woman, she is every woman, at some point, in some place. In this Firstpost series, we explore the ashtanayika, their representation in Indian classical dance and the place they find in contemporary times and practice. Read more from the series here . *** Desire — that fickle fiend, that contested feeling, that endless conundrum — has earned a notorious reputation in contemporary socio-cultural practice, so much so that talks of love and pleasure spark consternation: these are inappropriate subjects, meant to be discussed only in hushed whispers and as murmured gossip. To love is to present oneself to scrutiny, to be consumed by desire is frowned upon, and to talk about it, forbidden still. In utter contrast, the practice of Indian performing art celebrates sambhoga (union) vividly, interpreting desire not as a bodily function alone, but rather as a quest. It is a journey towards union, not only with the body, but also with the soul and very being of the beloved. So, when a vasakasajja | वसकसज्जा — a woman yearning for physical love — awaits the arrival of her beloved, with her eyes flitting constantly towards the entrance of the house, she longs for union with a companion whose affection is going to direct her towards a more fulfilling path. Within the traditional repertoire, desire is to be explored and savoured, and performing a vasakasajja becomes an exercise in portraying this agony of a woman pining for love. Often, such a recital depicts a frenzy bubbling within the nayika’s innermost self even as on the surface she appears to prepare herself sedately, in an almost leisurely fashion, to receive her lover. Sometimes, common tropes might involve depicting a sakhi – a close friend and confidante, in whom the nayika confides her increasing yearning. Mohiniyattam exponent Sujatha Nair recounts another interpretation in which her mother and guru, Jayashree Nair, flips the vasakasajja’s narrative. Instead of depicting the nayika, in this ashtapadi (a couplet with eight verses), the sakhi assumes the central role and becomes a messenger who describes the heroine’s condition to her lover, oftentimes Lord Krishna. The sakhi tells Krishna that the nayika has dressed herself up and is overwhelmed with desire; she is slipping into madness. She says, ‘When she doesn’t see you, she laughs, she cries, she laments and just sits there waiting for you.’ Portraying a vasakasajja through abhinaya becomes an exercise in balance and aesthetic: she is alluring but not overtly so, she is incomplete but instead of going to her lover, waits for him to come to her. And as she waits, she readies herself, knowing that her beloved will not stay away for long. Her movements are slow, seductive and deliberate as she tries to reign in the fluttering of her heart, lest it thrust her into that uncontrollable heady state. Such a nayika demands that a danseuse exult in her passion and sensuality, and often she is the sole character a performer plays on stage. First, the nayika steps out into her garden to gather sweet-smelling blossoms, and on returning indoors, sits with the flowers in her lap to weave a fragrant garland. One by one, she inserts the stalks of the little buds into the needle pushing them further along the thread, ties its two ends into a knot and gently places it down. From her wardrobe, she selects a bright saree or a colourful dupatta and drapes the fabric snugly around her body. Then, she loosens the knots in her hair, letting them trickle down her back. Picking up her comb, she gently brushes her tresses before braiding them and putting the fresh flowers in her plait. From her jewellery box she picks out many jingling bangles, earrings, a bindi and a long necklace that rests on her chest. Then, she picks up a mirror, and gazing at her reflection, she takes in this vision of herself. The verses of a lyric or thumri composed by the noted poet Binda Din Maharaj contain a beautiful description of the nayika going about this ritual: Malati gundhaye kesh pyare ghungarale (She weaves malati flowers into her beautiful curls) Maang motina sajayi, choti pith par kari (She adorns her forehead with pearls, and a long braid rests on her back) Sab ban than aayi shyam pyari re. (She dresses herself up as this lovely evening approaches) This refrain is the poet’s play on the word shyam, which stands for evening but is also one of the many names of Krishna. So the nayika awaits the pleasure of evening as much as she awaits her lord. He goes on to say: Mukh damini si damakata chal matavari (Her face shines like the lightning and she walks in an arousing way) In drawing a parallel between the heroine’s face and the blazing lightning, the poet describes a brilliance exuded by the vasakasajja that is brighter than her pearls. An inner radiance lends a warm glow to her face as she revels in anticipation. To locate a similar yearning in the contemporary context is to understand the simplest acts of a woman that symbolise love and attraction. This expression of desire is perhaps not as transparent, but Nair points out, it prevails. “Maybe we will not be standing in front of a tree making garlands, but on a personal level I know somebody who has actually said, ‘Oh my husband is coming back from work and I’d better put mogre ka haar (a garland of jasmines) and wait for him.’” [caption id=“attachment_9754501” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  A vasakasajja makes the bed while waiting for her beloved. Image via Wikimedia Commons[/caption] For a vasakasajja, enhancing her inherent beauty with such accessories fills the interminable hours of anticipation. This is her effort to appear desirable, the way she interprets it, because no matter how the idea of attractiveness changes and evolves across eras, the pursuit of physical love continues to be inextricably tied to being beautiful to oneself and one’s partner, in body and mind. A sanitised expression or celebration of such passion could well be an import of Western education, Nair remarks, when in fact, “it is part of our culture.” She supplements this point by invoking the Khajurao temples in Madhya Pradesh, known for their erotic sculptures. Despite the debate around it, sexual yearning as a manifestation of love continues to be experienced as a longing, or a feeling of incompleteness, or even lust that a woman enjoys as she navigates her own bodily desires. Kathak, a classical dance form with roots in storytelling, allows for a depiction of this desire which is at once subtle and emotive. The abhinaya of this dance form closely resembles everyday expressions of human interactions, perhaps more so than any other Indian classical dance, thus becoming a meaningful vehicle to express desire as a complex set of feelings. In depicting a vasakasajja putting her boudoir in order, arranging her pillows, making her bed, decorating it with rose petals and burning incense to flood her room with an intoxicating perfume, the movement vocabulary highlights every part of her body and of the physical space she inhabits, emanating a strong desire for sensual pleasures. The 12th century poet Jayadeva’s verses resonate with this eagerness and anticipation when he writes in his text Geet Govinda (a collection of ashtapadi that celebrate the relationship between Radha and Krishna): Patton ki aahat se aane ki jab shanka hoti, Saja aang mridushaiyyasakpar, utsukh hai aati hoti (The rustling of leaves indicates the arrival of her beloved, and she longs for him to reach her as she lies on her bed.) It is her longing, her anticipation and her preparation that is at the centre of this heroine’s narrative, perhaps making her the only ashtanayika to be immersed so thoroughly in physical conquests and bodily desires where no other predicament influences her responses, except this all-consuming yearning.

This series is an exploration of the ashtanayika of classical dance — the eight types of heroines which depict a woman’s many thoughts and emotional states. In part 3, a look at the vasakasajja.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)