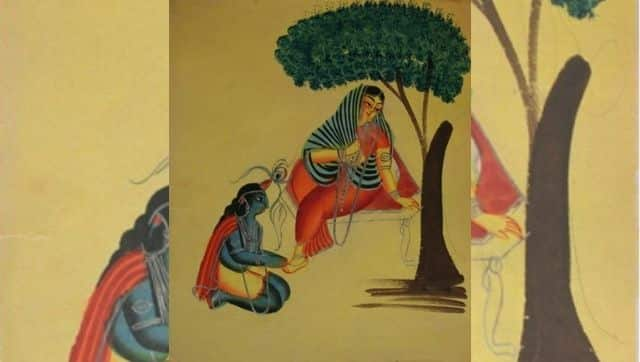

A nayika delights, saddens, bewitches, angers. In many ways, she provides catharsis, because her unabashed narration of her story – her woes, apprehensions and joys – evokes those emotions of love and desire within ourselves, whose existence we perhaps knew not of. In his Natyashastra_, written circa 200 BC, Bharat Muni expounded his theories on the practice and performance of theatre and dance in 36 chapters. It was within these verses that he crafted the ashtanayika, or the eight heroines based on eight different episodes from a woman’s life. The ashtanayika give voice to the thoughts of a woman caught in myriad situations concerning her lover, and are considered to be among the most beautiful and enduring forms of abhinaya in the study of Indian classical dance._ For centuries, each one of these instances has signified much more than the depiction of a woman’s conundrums and perils: they have come to denote her liberty to express herself, and her love — physical and spiritual — for her beloved. This is perhaps one of the reasons the concept of the nayikas has been nurtured through time, evolving with the world around it, while staying rooted to its essence. For a nayika is one woman, she is every woman, at some point, in some place. Read more from the series here . *** “He makes me happy.” For a swadhinapatika | स्वाधीनपतिका, happiness lies in sweet union, joy is found in the company of the lover, and childlike innocence is cast aside in favour of the newly discovered delights of love. A swadhinapatika knows what it means to experience pleasure, assumes an elevated status in the heart and soul of her beloved, and is confident of his unflinching loyalty and love towards herself. She positively radiates joy because of this explicit and vocalised trust between the two lovers. It is not enough that the beloved is attracted to the nayika intellectually and physically; that she knows and trusts his feelings is what makes this relationship special. As do the multiple meaningful gestures he employs to express his love. That this heroine and her beloved are immersed in the bliss of affection and togetherness is evident in the nayika’s coy smile, her teasing glances, her halting breath and the importance she gives herself. As her story unfurls on stage, so too is the audience reminded of their moments of love: of being the centre of a lover’s attention. The swadhinapatika enjoys this indulgence, since her beloved is driven by the singular motive of making her happy. In an Indian classical dance like Kuchipudi, which is embedded in dance-drama, this sambhoga shringara (love in union) makes for a mesmerising depiction of the nayika through an exploration of lokdharmi abhinaya, a medium of expression that borrows gestures from the folk vocabulary. Coupled with a traditionally emotive movement vocabulary, the abhinaya produces an overpowering, even theatrical effect. The Telugu padams composed by the prolific 17th century poet Kshetrayya form an extensive part of the Kuchipudi repertoire, and in these verses, the beloved or ‘lord’ is invariably the Muvva Gopala, or Krishna. Kuchipudi danseuse Prateeksha Kashi explains that in the swadhinapatika handed down to her by her mother and guru Vyjayanthi Kashi, Kshetrayya imagines himself to be the consort of the Muvva Gopala, simultaneously addressing his composition to and describing the love of, the lord himself. The nayika says to her sakhi — a close friend: Enta chakkani vade na sami veedenta chakkani vade (What a handsome Lord, What a charming Lord!) She confides in her sakhi about those aspects of an intimate romance that “a person would share only with a very close friend,” Kashi says. In the sanchari (episode) that precedes the verses, Kashi establishes this imperative detail by setting the stage for a conversation between two bosom friends. Then as the verses follow, she goes on to talk about the beauty of her lord: Chiruta prayamu vade chelu, vonda vidiya chan Duru geru nosala che merayu vade Cheraku vittuni ganna doravale nunnade Merugu chamana chaya menamaruvade (He is young and brilliant. His eyebrows are like the crescent moon. He is the father of Manmadha who is holding a sugarcane as a bow. His sky-blue body glistens and is attractive.) While the infatuated heroine describes these physical and intellectual attributes of her beloved, she recalls from memory his efforts to shower his love upon her. She attributes her happiness to her beloved. Filled with praise for her Muvva Gopala, she asserts: “Oh my sakhi, this Muvva Gopala of mine makes my heart very happy.” At the same time, she teases her beloved just as much. For instance, Kashi points out that when the poet compares the beloved’s strong hands to ‘the trunk of an elephant,’ she portrays the nayika with her back to him as he wraps his arms around her waist. She enjoys the embrace but turns to him and suggests through abhinaya, ‘Your arms are as strong as an elephant’s trunk, when you hold my waist which is so delicate, won’t it break?’ What’s notable in this little exchange is a mutual respect, because when the nayika complains that her beloved’s touch is too firm, he turns “very, very gentle. He understands what she needs.” Kashi notes that Kshetrayya’s verse is perhaps his way of “suggesting what a good relationship needs to have.” However, the popular perception of attraction of this sort is that it is servility; the beloved (read: man) is wrongly thought to be a slave to the woman’s needs. Popular culture also considers it emasculating for a man to paint his wife’s toenails or brush his girlfriend’s hair — acts that are rooted in care — especially when the knowledge of such actions become public. [caption id=“attachment_9794881” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  A swadhinapatika with her beloved, who, in the traditional repertoire is most often than not, Krishna. Image via Wikimedia Commons[/caption] In stark contrast, in an age-old ashtapadi (a poem with eight verses), Radha unhesitatingly asks Krishna to braid her hair. “She even specifies how she wants it. She demands things from a man,” Kashi explains. This is a request she makes not simply out of love, but out of faith in the lover’s unequivocal devotion to her, and she simply enjoys it. The swadhinapatika continues to be interpreted in different ways within the classical repertoire itself, and one such definition describes her as a woman whose beloved is very dependent on her for his happiness. Historically, Kashi explains, the act of making a partner happy would lie in simple things like playing kavade (akin to a board game), but today, because the pace of life has accelerated manifold and the exposure of both urban men and women to the world is so much greater, there are a lot of different attitudes and ideas that shape the happiness of a woman. In the contemporary urban context, “there are many couples who like to play a sport together, like tennis,” Kashi suggests, “I also see many couples travel together.” Sometimes just having a heartfelt conversation at the end of an exhausting day of work is enough to make a woman happy. Another component that holds relationships together is a sense of personal space for either partner — a notion that has been discussed more frequently in recent years. Sometimes a married couple may feel that being together all the time is not conducive for their relationship. Or, in the case of the unmarried ones, regular chats and video calls may suffice for a contemporary swadhinapatika, for whom the condition of seeing each other every day is not necessary for the relationship to sustain. A swadhinapatika beams with the excitement of young love, but her nature evolves with age and lived experience. As a young woman, she may dress up in vibrant colours and desire the same sense of spirit from her beloved. There will be a shift in expectations when the couple is newly married, perhaps in the form of consistent emotional support in an unfamiliar setting. And as they grow old together, the swadhinapatika will mature further, desiring simple things like the husband looking after the house when she steps out for an evening. By her very nature, however, the swadhinapatika remains a woman swept off her feet by her lover, making her the most fulfilled of all the ashtanayika. In effect, she is the only heroine whose beloved is a constant presence in her story, symbolising the ‘happily ever after’ of her own fairy tale.

This series is an exploration of the ashtanayika of classical dance — the eight types of heroines which depict a woman’s many thoughts and emotional states. In part 5, a look at the swadhinapatika.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)