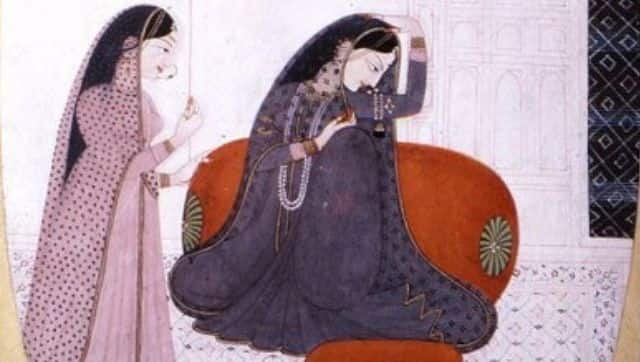

A nayika delights, saddens, bewitches, angers. In many ways, she provides catharsis, because her unabashed narration of her story – her woes, apprehensions and joys – evokes those emotions of love and desire within ourselves, whose existence we perhaps knew not of. In his Natyashastra_, written circa 200 BC, Bharat Muni expounded his theories on the practice and performance of theatre and dance in 36 chapters. It was within these verses that he crafted the ashtanayika, or the eight heroines based on eight different episodes from a woman’s life. The ashtanayika give voice to the thoughts of a woman caught in myriad situations concerning her lover, and are considered to be among the most beautiful and enduring forms of abhinaya in the study of Indian classical dance._ For centuries, each one of these instances has signified much more than the depiction of a woman’s conundrums and perils: they have come to denote her liberty to express herself, and her love — physical and spiritual — for her beloved. This is perhaps one of the reasons the concept of the nayikas has been nurtured through time, evolving with the world around it, while staying rooted to its essence. For a nayika is one woman, she is every woman, at some point, in some place. Read more from the series here . *** In the Ramayana, when Laxman followed his brother Ram and sister-in-law Sita to the forest on a fourteen-year-long exile, he left behind his wife Urmila to do her duty towards their family, as he would do his. As she prepared to bid him goodbye, Urmila appealed again and again to Laxman, imploring him to rethink his decision; when the moment of departure approached, she pleaded with him to take her along, and when he left at last, she let an insurmountable grief take over her being. Urmila is the archetypical proshitapatika | प्रोशितपतिका, a nayika whose husband or beloved has travelled to a faraway land. Much like Urmila, this heroine’s affliction is preceded by two stages of anguish before she fully transforms into a proshitapatika. She is first a pravatsyatpatika, overwhelmed with grief at the knowledge of her beloved’s impending journey, and then a pravasatpatika, one who is in the process of bidding him a final farewell. When his footsteps recede and she closes the door, when days turn into weeks and her beloved remains away, it is only then that she becomes the proshitapatika or the proshitabhartrika, a heroine suffering great sorrow because of this separation. Most often, within the traditional repertoire, it is this third phase which a performer seeks to unravel, as a culmination of anxiety and melancholy that completely overwhelms the nayika. Worried about her lover’s well-being, a grey cloud of misery constantly hangs over her head, and weakened in spirit, she spends hours lost in the thoughts of her beloved. A proshitapatika is a nayika whose sorrow engulfs her so completely that she loses interest in all worldly pleasures, ceases to look after herself, barely touches her food, casts away her finery, takes off her jewels and shrouds herself in gloom. Kuchipudi exponent Prateeksha Kashi notes that this nayika represents a sharp and bitter taste of the vipralamba shringara (love in separation) that follows the saccharine quality of sambhoga shiringara (love in union). More often than not, a proshitapatika evolves from a swadhinapatika – a nayika who enjoys the complete attention of her lover and spends many moments of togetherness with him. When he is compelled to go away from her and travel to distant lands, her pain is that much greater. But contrary to a virahotkanthita, this separation is seldom a punishment or a tragedy; it is simply a function of responsibility and obligation. A proshitapatika is one whose lover journeys owing to a sense of duty towards his family or his nation. So there exists a continued trust and deep feelings of love despite the distance between the two lovers. Kashi notes, “There is not even the slightest hint of infidelity.” Knowing that her beloved is willing to stay apart to fulfil his duty towards his family reaffirms her belief in his commitment towards their shared responsibilities. Drawing on a padam composed by the noted Telugu poet Kshetrayya, Kashi says that contrary to popular depictions of situations where the male lover must depart, this nayika commands the deepest respect in her beloved’s heart. In Kshetrayya’s verses, the nayika extols the many virtues of her ‘Varada of Kanchi’ who gives her both dignity and significance in his life; she is both his inspiration and strength. She tells her sakhi – a close friend – that when her beloved was leaving, bound by his duty, “He touched my feet and said that what he is now, is because of me.” And when the first onslaught of grief ebbs away, a proshitapatika reflects upon this admiration and love, thinking about the intimate moments she spent with her lover. In the padam, Kshetrayya captures the sorrow of Rukhmini who once stayed back in the town of Muvva, while her beloved journeyed to Kanchi. He wrote about the memories that she would recount to her sakhi and lament: ‘Ennitalacukondu namma! Yetlaamarapu vaccunamma…’ (How many times do I ruminate, O dear, how can I forget at all!) Speaking to her friend about the last conversation they had, she confesses, “With an assumed smile to cover his discomfort, having kissed me on my eyes, ears, neck and cheeks, the way he looked at me before going on tour, O dear, how can I forget it all!” Usually, a proshitapatika is a sweeya – one faithful to her lover or partner, who understands that the obligations he undertakes are for the greater good of the household. If there was ever a nayika who would become near obsolete owing to the advancements that science has made in the last few years, that would be the proshitapatika. [caption id=“attachment_9773711” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  A proshitapatika laments about her suffering to her sakhi. Image via Wikimedia Commons[/caption] In the contemporary urban age, as travel became faster, cheaper and safer, it led to immigration becoming a viable alternative, and most couples or families choose to journey together to try their fortunes in a foreign land. But until a few decades ago, Kashi points out, the father of a household would leave for another country and send money home for the family, unable to take his wife or children abroad due to multiple logistical constraints. Circumventing these constraints, the channels made available by technology in the form of video calls, emails and text messages have allowed lovers divided by distance to still enjoy proximity and intimacy, albeit of a virtual kind. “So, even if the beloved goes out on a journey, you are constantly in touch,” Kashi remarks, “you may probably not miss him as you would in those days because you never had any of these things to constantly keep you in touch with each other.” For a proshitapatika, there is comfort in the simple knowledge that her beloved is faring well. According to Kashi, the essence of this heroine lies in the communication she enjoys with him, so being able to gauge his well-being is enough to soothe her nerves. In spite of her distress, she is reassured when her lover acknowledges her sacrifice and her sorrow. As Kashi opines, “Most times, it becomes very important to deliberately say that out loud to your partner.” Yet, just as lovers were separated in the past when men were sent off to war, so too in the contemporary context there exist many proshitapatikas, Kashi suggests, who bid their partners in the armed forces adieu each time a posting to a vulnerable location has them leaving their families behind. And there exists this nayika in every home today, she adds, where a frontline worker steps out of the house each morning in the middle of a pandemic, into the thick of a war raging in hospitals, nursing homes and clinics, and the person left behind is continually afraid, even though the beloved isn’t on a journey, strictly speaking. To understand the predicament of a proshitapatika is to explore those emotional conundrums experienced by two lovers when one of them must perform a duty far superior than their personal desires. In a dance form like Kuchipudi, immersed in lokdharmi abhinaya, Kashi explores this quandary in a production on Urmila. In it, in a juvenile and tearful state, she wonders why Queen Kaikeyi who demands Ram’s dethroning couldn’t have uttered 14 days, rather than 14 years of exile. Wrestling with a madness threatening to burst out of her, she asks her husband, “If Ram is bringing Sita, why can’t I come with you?” To her question, Laxman replies simply, “If you stand in front of me, Urmila, I can’t see Sita, and if you stand behind me, I can’t see you at all.” Instead, he promises, “I will come back, and we will be together again,” and as Urmila becomes a proshitapatika, as she comes to grips with her sorrow, she derives solace from this declaration: words that could act as a balm to sooth a gaping wound, perhaps over time.

This series is an exploration of the ashtanayika of classical dance — the eight types of heroines which depict a woman’s many thoughts and emotional states. In part 4, a look at the proshitapatika.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)