the priest (foaming against custom) condemned

the condemned soul to a second hanging, his epitaph, a palimpsest And to the officer prepared to free the almost-hung: it’s holier than silence, this ignoring a lord who absolves thick-necked vermin *** Dated 1748 and set in the French colony of Pondicherry, Arjun Rajendran writes about the second hanging of a convict in the titular poem of his latest collection, One man: Two executions. When the noose breaks during the unfortunate incident, the priest orders the executioner to disregard this holy sign and hang the man whom divinity had spared. Such and many other incidences of bizarre nature are to be found in the Pondicherry of Rajendran’s musings, conjured against the backdrop of a province embroiled in the Carnatic wars. The Private Diaries of Ananda Ranga Pillai which chronicle the events of 18th century Pondicherry, form the historical influences that drive much of the setting in Rajendran’s poems; still others, like the minute interiority of the town and its people can be attributed to the realm of the poet’s imagination. Pillai’s diaries can be traced back to the time before he was appointed the dûbash (interpreter) to the French governor of the time, Joseph François Dupleix. These records, the poet says, were discovered and published posthumously, and contained “details of maritime trade, executions, coinage, battles, personal tragedies and rivalries with Dupleix’s wife – the governess.” In 2017, two years after his father introduced him to the sheer volume of historical texts that Pillai had left behind, Rajendran began his research by navigating his way through the tomes of literature, and noting down every snippet that carried an interesting detail. With each volume spread across 600 pages and more, eventually the poet settled on a method of “historical confabulation”, which meant “imagining narratives to prolong the usually dry facts offered by the diarist.” [caption id=“attachment_9061911” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Arjun Rajendran’s One man: Two executions[/caption] Pillai was recording a tumultuous period in Indian history. Rajendran calls to mind the decades that witnessed the decline of the Mughal Empire and the mounting conflicts between numerous factions, including the Marathas, the colonial powers like the Dutch, French, Portuguese and the English. It is no surprise then that many of Rajendran’s verses re-imagine the politics, betrayals and dramas of this era. But what his poetry invokes beautifully is almost a haunting maritime imagery – of massive vessels anchoring at Pondicherry’s harbour and the treasures, thieves, smugglers and pillaging pirates they brought ashore. A passionate description involves Rajendran talking about “ships, magnificent and imperial that were crowning the horizon and lending their rum-stained vocabulary to the shores of the Mascarene Islands, Tenasserim, Bencoolen, Mocha and of course, Pondichéry.” “Each time a significant vessel pulled into harbour,” he continues, “seventeen gun salutes would be fired from the fort’s ramparts to welcome it. Oh, and they had the most gorgeous names: Jupitre, Marie Gertrude, Aimable, Chandernagor, Quatre Soeurs, Duc D’Orleans…” To Marie Gertrude he dedicates a verse, describing the frigate in conflict. When it was a work in progress, the poet’s attempt was to

structure

the poem in such a manner that “the stanzas resemble the bow and stern of a ship.” In 2018, Rajendran was awarded the Charles Wallace Fellowship for Creative Writing and spent months composing poetry at the University of Stirling in Scotland. The highlight of the fellowship, according to him, was this very poem being “published on a glass wall of the Department of Literature and Humanities” at the university. In other works like Pirate, he makes poetry out of someone’s personal recollection of a romance novel and gives it a historical context. All the while, the feeling of being carried away by the tides on a majestic vessel is constant: when I heard you mutter pirate, pirate in sweet kidnap, sadism your breath ripping away the topmast, its skull and crossbones burying us under savagery… On the other hand, he bases The Storm “around the time the celebrated French admiral, La Bourdonnais, betrayed Dupleix and fled to France after looting Fort St George in Madras.” He writes: Anchored in his disbelief is the ship, Subterfuge; its supercargo, betrayal The governess – her ear to his heart – Perceives the eye of the storm, christens it La Bourdonnais … It was a most remarkable period in the age of sail, the poet concedes, and to resurrect the extinct he explains: “I had to invoke the ghosts of lascars, boatswains, cafres, admirals and pirates.” “I had to turn my inner demons into a kraken and calculate my voyage using astrolabes, spyglasses and sextants.” *** Complete with a host of themes that range from history to love to science fiction and at times even sarcastic jocularity as is the case with Why Aliens Shun India, Rajendran’s latest collection was a project three years in the making. His process of writing poetry involves an extensive gestation period in which an idea is stored in his mind for months before it is poured on to a page. Of the process that goes into crafting the verses, he had remarked in

an interview

that “the first and last lines are usually the ones I edit the most, and these are often the poem’s most persuasive critics…” This collection, however, is markedly different from his earlier works like The Cosmonaut in Hergé’s Rocket or Snake Wine, because it involved simultaneously representing and inventing a historical period. With the creative liberties, he also saw risks, “and to sustain the ambiance and to unmoor myself from established patterns was quite the challenge,” he confesses. “Also, this is the first book where I have incorporated strikeouts extensively — to suggest the fragility of memory, of civilisation itself.” Of the powerful connotations in his poems that highlight the politics and hypocrisy inherent in society, he admits that his “starkly political poems come with a heavy dose of speculation, in that, I have incorporated science fiction and fantasy tropes that have to be negotiated before reaching the crux, if there is a crux to be reached at all.” Following the coronavirus outbreak, the poet has embarked on another poetry initiative, The Quarantine Train, which began with his desire to conduct a workshop. Over the months that followed the lockdown, the project has grown and now comprises a core team of writers who host critiquing and appreciation sessions and guest lectures by poets and scholars from across the world. With the collective, it was the poet’s aim to bring together a consortium of writers and members who are seriously interested in literature, and to create a virtual space for interaction with literary aficionados during this rather isolated time of quarantine and social distancing. *** Rajendran’s 2020 collection, One man: Two executions is divided into three parts: Pondichéry, The Girl in the Peapod and Were It Not For. A series of love poems, it is in the second section that the inter-linguistic element of Rajendran’s poetry becomes prominent through a harmonious fusion of English and French that renders a musical quality to his verses. [caption id=“attachment_9061921” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Arjun Rajendran’s One man: Two executions[/caption] Pillai was recording a tumultuous period in Indian history. Rajendran calls to mind the decades that witnessed the decline of the Mughal Empire and the mounting conflicts between numerous factions, including the Marathas, the colonial powers like the Dutch, French, Portuguese and the English. It is no surprise then that many of Rajendran’s verses re-imagine the politics, betrayals and dramas of this era. But what his poetry invokes beautifully is almost a haunting maritime imagery – of massive vessels anchoring at Pondicherry’s harbour and the treasures, thieves, smugglers and pillaging pirates they brought ashore. A passionate description involves Rajendran talking about “ships, magnificent and imperial that were crowning the horizon and lending their rum-stained vocabulary to the shores of the Mascarene Islands, Tenasserim, Bencoolen, Mocha and of course, Pondichéry.” “Each time a significant vessel pulled into harbour,” he continues, “seventeen gun salutes would be fired from the fort’s ramparts to welcome it. Oh, and they had the most gorgeous names: Jupitre, Marie Gertrude, Aimable, Chandernagor, Quatre Soeurs, Duc D’Orleans…” To Marie Gertrude he dedicates a verse, describing the frigate in conflict. When it was a work in progress, the poet’s attempt was to

structure

the poem in such a manner that “the stanzas resemble the bow and stern of a ship.” In 2018, Rajendran was awarded the Charles Wallace Fellowship for Creative Writing and spent months composing poetry at the University of Stirling in Scotland. The highlight of the fellowship, according to him, was this very poem being “published on a glass wall of the Department of Literature and Humanities” at the university. In other works like Pirate, he makes poetry out of someone’s personal recollection of a romance novel and gives it a historical context. All the while, the feeling of being carried away by the tides on a majestic vessel is constant: when I heard you mutter pirate, pirate in sweet kidnap, sadism your breath ripping away the topmast, its skull and crossbones burying us under savagery… On the other hand, he bases The Storm “around the time the celebrated French admiral, La Bourdonnais, betrayed Dupleix and fled to France after looting Fort St George in Madras.” He writes: Anchored in his disbelief is the ship, Subterfuge; its supercargo, betrayal The governess – her ear to his heart – Perceives the eye of the storm, christens it La Bourdonnais … It was a most remarkable period in the age of sail, the poet concedes, and to resurrect the extinct he explains: “I had to invoke the ghosts of lascars, boatswains, cafres, admirals and pirates.” “I had to turn my inner demons into a kraken and calculate my voyage using astrolabes, spyglasses and sextants.” *** Complete with a host of themes that range from history to love to science fiction and at times even sarcastic jocularity as is the case with Why Aliens Shun India, Rajendran’s latest collection was a project three years in the making. His process of writing poetry involves an extensive gestation period in which an idea is stored in his mind for months before it is poured on to a page. Of the process that goes into crafting the verses, he had remarked in

an interview

that “the first and last lines are usually the ones I edit the most, and these are often the poem’s most persuasive critics…” This collection, however, is markedly different from his earlier works like The Cosmonaut in Hergé’s Rocket or Snake Wine, because it involved simultaneously representing and inventing a historical period. With the creative liberties, he also saw risks, “and to sustain the ambiance and to unmoor myself from established patterns was quite the challenge,” he confesses. “Also, this is the first book where I have incorporated strikeouts extensively — to suggest the fragility of memory, of civilisation itself.” Of the powerful connotations in his poems that highlight the politics and hypocrisy inherent in society, he admits that his “starkly political poems come with a heavy dose of speculation, in that, I have incorporated science fiction and fantasy tropes that have to be negotiated before reaching the crux, if there is a crux to be reached at all.” Following the coronavirus outbreak, the poet has embarked on another poetry initiative, The Quarantine Train, which began with his desire to conduct a workshop. Over the months that followed the lockdown, the project has grown and now comprises a core team of writers who host critiquing and appreciation sessions and guest lectures by poets and scholars from across the world. With the collective, it was the poet’s aim to bring together a consortium of writers and members who are seriously interested in literature, and to create a virtual space for interaction with literary aficionados during this rather isolated time of quarantine and social distancing. *** Rajendran’s 2020 collection, One man: Two executions is divided into three parts: Pondichéry, The Girl in the Peapod and Were It Not For. A series of love poems, it is in the second section that the inter-linguistic element of Rajendran’s poetry becomes prominent through a harmonious fusion of English and French that renders a musical quality to his verses. [caption id=“attachment_9061921” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

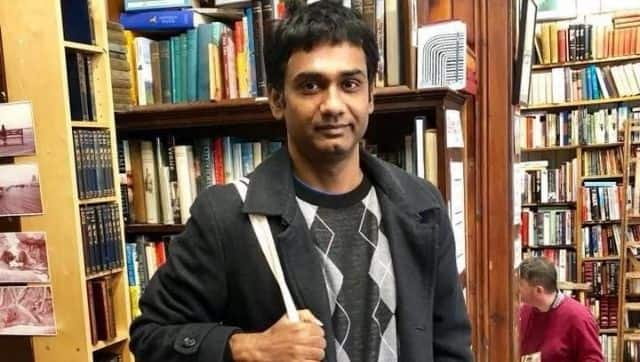

The inter-linguistic element in Rajendran’s verses gives an almost elegant and musical quality to his work. Image via Facebook[/caption] As editor of The Bombay Literary Magazine, a platform that publishes fiction and poetry, the poet says he often comes across poems that are inter-linguistic, “Marvellous pieces, really, that blend seamlessly into another tongue.” For Rajendran, it was pursuing his advanced levels in French through Alliance Française that led him, like a regular linguist, to think and switch between the two languages. In the dystopian Movie Date, he writes about a couple going to the theatre in an ‘antiquated pod’: …We park our pod in the most inconspicuous spot. Ce n’est pas assez caché, you grumble. He continues: “One poem in fact, Of an Alien Moon, was originally written by me in French and then translated into English – the first time I have ever done that.” When this writer breaks into French to find out if the poet has embarked on ‘un nouveau projet de la poésie,’ or a new poetry project, the delighted Francophile responds, “J’ai quelques pensées mais je crois que je devrais lire beaucoup de livres avant de commencer un nouveau projet. D’ailleurs, je n’ai aucun idée si je choisirai de suivre un chemin thématique ou mélangé en ce moment.” (I have thought about something, but I believe I must read a lot before starting a new project. Besides, I have no idea at the moment if I will choose to follow a theme or mix it up.) Arjun Rajendran’s ‘One Man Two Executions’ has been published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications.

The inter-linguistic element in Rajendran’s verses gives an almost elegant and musical quality to his work. Image via Facebook[/caption] As editor of The Bombay Literary Magazine, a platform that publishes fiction and poetry, the poet says he often comes across poems that are inter-linguistic, “Marvellous pieces, really, that blend seamlessly into another tongue.” For Rajendran, it was pursuing his advanced levels in French through Alliance Française that led him, like a regular linguist, to think and switch between the two languages. In the dystopian Movie Date, he writes about a couple going to the theatre in an ‘antiquated pod’: …We park our pod in the most inconspicuous spot. Ce n’est pas assez caché, you grumble. He continues: “One poem in fact, Of an Alien Moon, was originally written by me in French and then translated into English – the first time I have ever done that.” When this writer breaks into French to find out if the poet has embarked on ‘un nouveau projet de la poésie,’ or a new poetry project, the delighted Francophile responds, “J’ai quelques pensées mais je crois que je devrais lire beaucoup de livres avant de commencer un nouveau projet. D’ailleurs, je n’ai aucun idée si je choisirai de suivre un chemin thématique ou mélangé en ce moment.” (I have thought about something, but I believe I must read a lot before starting a new project. Besides, I have no idea at the moment if I will choose to follow a theme or mix it up.) Arjun Rajendran’s ‘One Man Two Executions’ has been published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications.

)