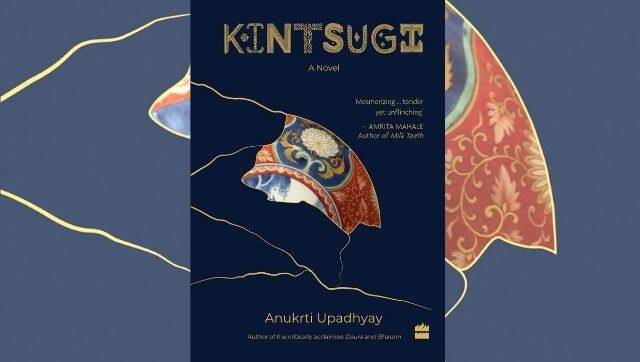

Kintsugi, the Japanese art of mending broken objects with gold, finds its way into Anukrti Upadhyay’s latest novel — a blend of different stories, of broken characters spread across the jauhari bazaar of Jaipur to the cityscape of Tokyo. Through her characters — Meena’s rebellion in escaping to Japan and Haruko’s discipline as she learns the craft of jewellery making, in Prakash’s cowardice and Yuri’s insecurities — Upadhyay’s Kintsugi weaves two seemingly contradictory worlds together, exploring sexuality, immigrant complexes and brilliant craftsmen hiding their art from the women of the family. Her novel dwells on the coveted art of jewellery making, breathing life into beautiful traditions such as kundan, meenakari and thewa which have largely remained absent from the Indian literary canon, while offering a glimpse of the age-old gaddis in Jaipur which carry forward the business of intricately crafted artisanal jewellery. In a conversation with Firstpost, the author of the companion novels Daura and Bhaunri, shares what draws her to Japanese culture and literature, her love for the artisanal jewellery of Rajasthan and what it means to be a bilingual author, juggling Hindi and English to write compelling novels and short stories. Edited excerpts: Could you elaborate on how you were inspired to write this story, particularly how each character symbolises the art of kintsugi that your book is named after? I wrote Kintsugi, the original draft, some four years ago. I write in pencil in a notebook and then I type it out, which means a complete rewriting. So the form in which the book is now must be the seventh or eighth version. But it started out as one story which I began writing in Hakone. That was my first visit to a Japanese onsen, a hot water spring. The sensory stimulation of that place was such that I wanted to capture it in words. So the first bit of Kintsugi that I wrote was of Meena, the part where Meena and Yuri are in Hakone. When I wrote it I realised that there is more to be said and then various pieces came together. However, the title Kintsugi was suggested by my editor, Rahul [Soni] and I knew that it would be right because that’s how I had conceived it, as pieces that were broken but would still remain parts of a whole. [caption id=“attachment_8754381” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Anukrti Upadhyay’s Kintsugi brings to the fore the artisanal craft of jewellery making prevalent in Rajasthan through characters dedicated to taking this legacy forward.[/caption] How did you go about writing this cross-cultural narrative, reconciling the two beautiful cultural spaces, Japanese and Rajasthani, where the stories unfold? I was born and raised in Jaipur, so back in 2016 when I started writing seriously – up until then I used to write poetry or a lot of legal documents as I am a lawyer – I realised that Rajasthan came organically into my writing though I had not lived there now for over 20 years. I didn’t realise how deeply I felt connected to this place, perhaps in many ways nostalgic for what used to be. I also wanted to capture the various facets which I feel are bit under-explored in fiction. Nobody writes about how glorious the jewellery craft is. It was also a metaphor I employed, because to create anything of beauty requires patience and it takes patience to build lives, to build relationships, to express and find yourself. I first visited Japan in the winter of 2005 and I was smitten. It offered so many contradictions that the place felt almost unreal because of their starkness. I also found Japanese literature endlessly fascinating. Both fascinations came together – my need to talk about my own heritage and an aesthetic society which completely intrigued me. Could you tell us about some of the Japanese literature you have been reading and works which have particularly stood out for you? I have read old Japanese masters like Natsume Sōseki to Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, to the modern writers from Haruki Murakami to Hiromi Kawakami to Minako, to every new Japanese work coming out in English. I think my favourite however is Jun’ichirō Tanizaki who wrote at the cusp of change coming into Japanese society. At the time, Japan became an aggressor during World War II and then they realised that they had lost. In the process of losing the war, in many ways they lost a sense of identity. It is strange because Japan has such a pronounced cultural heritage, nurtured through isolation and yet that defeat created a crisis of identity for Japan as a nation and that’s the period Tanizaki sensei writes about. Could you share with us your experiences of interacting with the local sunars while researching for Kintsugi? What are some of your favourite ornaments crafted in their artisanal styles? Rajasthani women are very fond of their jewellery and I am no exception. All my life I have seen my mother, grandmother, sisters, buying jewellery, talking about jewellery but when I started writing Kintsugi, I realised I wanted to know more, so I actually went into the jauhari bazaar lane. Our family jeweller introduced me to some of the artisans there and I spent days sitting there observing what they were doing. I also saw how the presence of a woman in the artisans’ room, a hole in the wall tucked somewhere in a haveli in Jaipur, was very unusual for them. When I started asking questions about the sunar tradition, I learnt that women are not allowed to learn jewellery craft. My favourites are works which are a combination of meenakari and kundan because this embodies all kinds of contradictions. The enamel work requires firing while kundan requires very delicate handling and even a lick of a flame could ruin it. So the two things balanced in one piece of ornament is an aesthetic that attracts me and also that the hidden parts of the ornament are sometimes more beautiful than the exposed part.

To me it’s the ultimate artistic arrogance: you create beauty that is for nobody else’s eyes except the eyes of the wearer.

My best loved pieces are a set of kundan and meena bracelets. It is white meena which is not very common, and difficult to craft because the colour of the other enamel work may leak into the meena and spoil it. In so many ways, Yuri, a child abandoned by her mother, symbolises a co-dependency arising out of insecurity. How did you shape her story, her desperation and in the end, the resignation which leads her to take an extreme step? To me in many ways, Yuri symbolises Japan because on the outside she is so calm, gentle and composed, you feel she has got all the strength in her head. To me Japan is like that, on the surface so calm and composed but go one or two layers deeper, you realise what a complex, contradictory social and psychological structure there is. Walk into any Japanese drug store, for instance, and you can see extreme graphic images of hyper-sexuality, violent orientations. For a women raised in Rajasthan, this is a shock because under the layer of this gentle, super-civilised, cultured and aesthetically aware society, there is this. Inside of Yuri, there is so much suffering, so much pain and co-dependence that she needed someone to hang on to, to just be. That comes from internal suppression. [caption id=“attachment_8754431” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  A bilingual writer, Upadhyay has to her name a collection of Hindi short stories, Japani Sarai which explores the crisis of contemporary life, of the new world we inhabit. Image courtesy: Yashodhar Sharma[/caption] In your book, you talk about fusing ‘the pure with the frail without melting or breaking the other.’ How do you strike that balance in writing stories which at once highlight the prevalent rigid conformity to traditions while appreciating age-old indigenous arts? Artisanal traditions which are such an important part of Kintsugi symbolise things we mustn’t throw away. Look at Prakash, what a wasted life he led, completely unexamined. He can’t even dare to face the truth, except in a dream. He just is not able to confront his own self and his own life. So that’s what the traditional crafts symbolise. And Meena’s rebellion: you know it’s the character I most wrote about but liked the least. She is a chaotic personality. She has no idea of herself. She knows what she doesn’t want however she does not very clearly know what she wants. So she tries to break away from her family without really breaking away. Women are raised a certain way, society has conditioned them. So if women hide things about their own self, they are just playing the cards they are dealt with. But if you are like Meena, there is something beyond it that you are not courageous enough to embrace wholly and therefore you wreck havoc in everybody’s lives. You have been writing in two languages, Hindi and English. Do you ever quarrel with yourself about the language in which you want to tell a story? I wrote poetry for the longest time and I wrote it all in Hindi. So in many ways, the language for the more spontaneous, emotional expression has remained Hindi. But interestingly when I started writing fiction, I wrote it all in English and there was never a dilemma. Even the stories of Japani Sarai … the first draft was written in English and then I transformed it in Hindi. It’s an interesting feature of bilingual writing that I am forever exploring both languages. Anukrti Upadhyay’s Kintsugi has been published by HarperCollins

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)