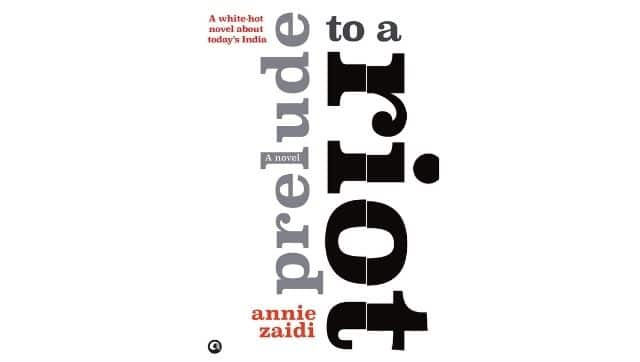

Annie Zaidi has an unusual metaphor for fiction: she likens its value in her life to veggies. Vegetables don’t just give proteins or nutrients; their existence also enables one to “describe what it means to eat vegetables, and to understand a world in which vegetables exist for only some people,” she tells Firstpost. Fiction, which she can’t delineate from other pursuits like poetry, film, plays, history, and journalism, does multiple things simultaneously that enable her to live a healthy life. “I could also say that it is the reading of fiction that enables me to understand, and articulate, the multiple, parallel meaning of vegetables.” As a writer, fiction is also her way of “dealing with most troubling things,” helping her cope, at least in the short term, with the unease she’s feeling. “In the long term, of course, nothing helps if one is surrounded by relentless hate.” Coping with troubling, bigoted conversations she’d heard is also what led to her debut novel, the JCB Prize-shortlisted Prelude to a Riot. Told from the perspective of multiple characters, it is set in an unnamed town in South India and details the growing communal tensions and religious intolerance that signal oncoming violence. The soliloquies that make up the chapters are a result of the notes Zaidi had from a research trip for a non-fiction article about labour rights on plantations. These included not just interview transcripts but also conversations she’d heard and documented. “There were ‘voices’ of a sort and when I began to sort my notes, I found that each of these voices was expressing something outwardly but also hinted at an internal conversation that the individual must inevitably have, especially when faced with domestic or platonic friction,” she says. It is to fully explore the inner world of these ‘voices’ that Zaidi turned to fiction. “Non-fiction doesn’t allow me to extrapolate or even to describe the associations between ideas that are absolutely clear to me, but which have not been expressed verbally by someone else,” she says. As an observer, for instance, it might be clear to Zaidi that the anger a bigot is expressing at an ‘other’ stems from jealousy or fear. “I may ‘see’ it as if it were a tangible object sitting on the table between us, but I cannot write it as non-fiction,” she explains. It is such nuances that each of Prelude’s characters exemplifies. [caption id=“attachment_8940401” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

All photos courtesy the publisher, Aleph Book Company[/caption] Through the character Majju, for instance, Zaidi’s work is reflecting the ruthlessness with which those in power go about retaining it. A 17-year-old migrant worker, Majju is found dead in a ditch two days after being seen with Yashika, an upper-class school student. “The transgression he is punished for is not his own. However, he is utterly powerless and is punished as a way to set an example to his community, which is a group of homeless migrant workers,” says Zaidi. In the book, Yashika’s history teacher Garuda also provides sharp commentary about her privilege: Dalliance with a plantation hand, a bad memory. Or maybe a nice memory after all. Like tasting wild honey in the forest. A boy who never went to school. Smooth brown limbs, busy hands, steady eyes. You wanted a taste, didn’t you? Steadiness, strength. A boy who had nothing. You found a way to extract something even from him. Through another character, Saju, Zaidi shows how power structures affect one’s identity and sense of belonging. In the beginning, hated by his wife Devaki’s family because he belongs to a different caste, Saju understands that power is preserved through upholding dominant narratives and wants to dismantle discriminatory social structures. However, once married, he realises that resisting Devaki’s family means facing the wrath of powerful, dangerous men. “Humiliation and sustained rage are so unattractive. Who wants to be at the receiving end of it?” So slowly, he starts aligning himself with them through focusing on a common ‘other’, which also translates into a higher social status for him. “This is how power works in society. Dominant groups hold out the carrot of acceptance, if not equality, with one hand and with their other hand, they hold out the risk of violence,” Zaidi says. Through Saju, Zaidi highlights how the temptation of crossing barriers and moving a few notches up in the power structure can be incentive enough to surrender one’s individual identity and group affiliations. “Wanting to align with power is a natural impulse. It is understandable because the gains are manifold. Resisting power – especially power structures that deliberately shut you or a specific set of communities out – is also a natural impulse.”

All photos courtesy the publisher, Aleph Book Company[/caption] Through the character Majju, for instance, Zaidi’s work is reflecting the ruthlessness with which those in power go about retaining it. A 17-year-old migrant worker, Majju is found dead in a ditch two days after being seen with Yashika, an upper-class school student. “The transgression he is punished for is not his own. However, he is utterly powerless and is punished as a way to set an example to his community, which is a group of homeless migrant workers,” says Zaidi. In the book, Yashika’s history teacher Garuda also provides sharp commentary about her privilege: Dalliance with a plantation hand, a bad memory. Or maybe a nice memory after all. Like tasting wild honey in the forest. A boy who never went to school. Smooth brown limbs, busy hands, steady eyes. You wanted a taste, didn’t you? Steadiness, strength. A boy who had nothing. You found a way to extract something even from him. Through another character, Saju, Zaidi shows how power structures affect one’s identity and sense of belonging. In the beginning, hated by his wife Devaki’s family because he belongs to a different caste, Saju understands that power is preserved through upholding dominant narratives and wants to dismantle discriminatory social structures. However, once married, he realises that resisting Devaki’s family means facing the wrath of powerful, dangerous men. “Humiliation and sustained rage are so unattractive. Who wants to be at the receiving end of it?” So slowly, he starts aligning himself with them through focusing on a common ‘other’, which also translates into a higher social status for him. “This is how power works in society. Dominant groups hold out the carrot of acceptance, if not equality, with one hand and with their other hand, they hold out the risk of violence,” Zaidi says. Through Saju, Zaidi highlights how the temptation of crossing barriers and moving a few notches up in the power structure can be incentive enough to surrender one’s individual identity and group affiliations. “Wanting to align with power is a natural impulse. It is understandable because the gains are manifold. Resisting power – especially power structures that deliberately shut you or a specific set of communities out – is also a natural impulse.”

Annie Zaidi reflects on roots of her JCB Prize-shortlisted Prelude to a Riot, how power structures manifest in society

Aarushi Agrawal

• October 31, 2020, 16:28:49 IST

Readers who are willing to accept the stress and grief of being unpopular in their families and who continue to rail at discriminatory behaviour – they would make me happiest, says Annie Zaidi.

Advertisement

)

So while a sense of foreboding dominates the pages of Prelude, there are also characters resisting power. Hope in the fictive world comes from Garuda, reluctantly trying to encourage critical thinking in his uninterested students, and the liberal newspaper editor who refuses to sway in the face of moral policing. Both represent the set of individuals in society who drive positive change. “Many such individuals may add up to a particular political culture of reason and civilised debate.” Such a culture of respectful debate where one can speak without interruption, and is allowed to raise questions and rebuttals, is key to responsibly shaping public opinion. It also stands in sharp contrast to the way social and political debate is currently carried out on television screens or in Parliament. “The prerequisite for a healthy public debate is equity between participants, and a healthy country is one where everyone gets to participate,” Zaidi says. It is also such responsible individuals that Zaidi is most focused on sharing Prelude to a Riot with. “Readers who recognise that each of us play a role in shaping conversations in private and public domains, readers who can find the courage to challenge drawing room conversations, café conversations, WhatsApp conversations, readers who are willing to accept the stress and grief of being unpopular in their families and who continue to rail at discriminatory behaviour – they would make me happiest.” Prelude to a Riot is published by Aleph Book Company

End of Article