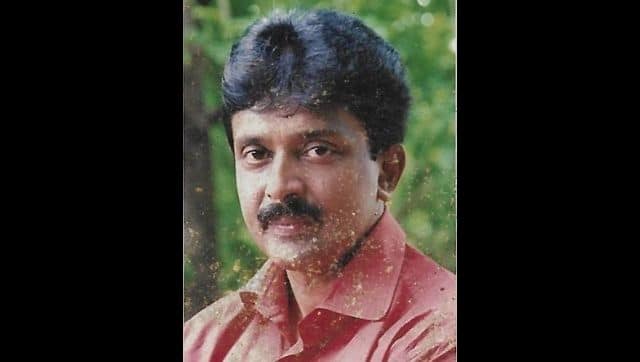

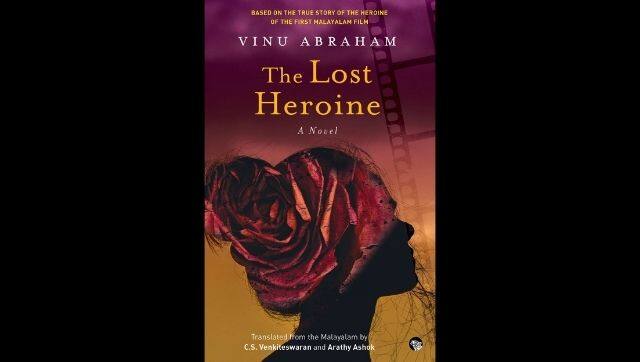

“When I first heard about the tragic plight of Rosy and Daniel back in 2005, the pioneering heroine and filmmaker in Kerala, I was really in shock. The uppermost thought in my mind was how could such an important chapter in Kerala history as a whole and of cultural realm in particular remain largely hidden for about 75 years. I felt that this is a story that should be reaching a wide audience.” With these ideas racing through his mind, screenwriter and author Vinu Abraham set off on a quest to dig into the life of the first-ever heroine of Malayalam cinema, PK Rosy and the first Malayalam movie ever made, Vigathakumaran (The Lost Child). Nashtanayika, the 2008 Malayali novel, was thus born, chronicling the creation of Vigathakumaran and interspersing real-life incidences with the writer’s imagination to fill in the gaps created by unrecorded history. The award-winning scriptwriter and novelist’s work recently merited an English translation with essayist CS Venkiteswaran and the English professor Arathy Ashok working in collaboration to produce The Lost Heroine. At the outset, Abraham was inclined towards writing a long feature, an article. “However very soon, I realised that hard core facts, particularly about Rosy, were very scarce,” he explains, “It was then that the creative writer in me took over,” and it was decided that the story would be written in a way which combined facts with fiction. [caption id=“attachment_8854051” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  In his book, the award-winning scriptwriter and author, Vinu Abraham sheds light on Rosy’s plight as a Dalit girl portraying an upper-caste woman.[/caption] Undoubtedly, there are several episodes in the book which the writer has plucked from his imagination of early 20th century Travancore. For instance, Abraham notes, in the story Rosy meets Ayyankali, a Dalit leader of that era. “While it is a fact that both lived in Thiruvananthapuram at the same time, there is no record to show that they ever met.” The book also describes an episode when Sethu Laxmi Bayi, whose reign prevailed in Travancore at the time, passes by the heroine of this story in a carriage on the street. So also the incident where one day while shooting in the studio, Rosy realises she has got her period and is scared stiff as she does not have any extra clothing. “All around it is only males and feeling helpless, she hides herself in the lavatory. Only when Janet, the wife of Daniel, comes to the studio she finds someone to share her predicament.” It was in 1928 that director-producer JC Daniel’s friend, Johnson, called on Rosy to audition for a film they would be making. With apparent disbelief and eyes full of dreams, this young Pulaya girl agreed. A fortnight later, she was standing in front of the camera, about to become ‘The first film heroine in this land of Malayalam.’ Thus begins the story of The Lost Heroine, whose aspiration of achieving recognition for her art was put to test time and again and whose identity was obliterated in its entirety except from within the few movie clips that survived. Abraham’s writing captures this anguish, whilst also providing a descriptive account of the making of the silent film more than ninety years ago. The film production process of that period was so different, the author says, that it meant doing a lot of research to accurately depict the shooting and release of the film in the novel along with the lives of its actors. “However, while in the case of Daniel, there were many materials available and there were two of his children I could meet, regarding Rosy, none of her own immediate family members were alive,” he recalls. Nashtanayika is then a product of three years of extensive research, a story which was also adapted by the veteran director Kamal into the 2013 Malayalam film Celluloid. This was a biopic on Daniel featuring the popular actor Prithviraj as the director and Chandini as Rosy. In the film within the novel, Vigathakumaran, Daniel essays the role of the hero, Jayachandran, but the star of the screen is Rosy – a poor girl living in a thatched hut with her Amma, Appan and siblings – who portrays, Sarojini, a lady belonging to a Nair tharavad. The book amply suggests to the reader that Rosy is a great actor, it is in fact her performance in the Kakkarissi folk plays that catch Johnson’s eye leading him to seek her out. But Rosy is by no means oblivious to her social station. As excellent an actor as she is, in the early phase of the shoot, Rosy is awkward, even scared because she is a Dalit girl acting on screen as an upper-caste woman. However, Abraham points out that while the caste system and the resultant discrimination were prevalent in Kerala at the time, the nascent film movement was far from casteist. The film’s shooting took place in Thiruvananthapuram and featured Daniel and Rosy, both of whom belonged “to underprivileged sections of the society in varying ways.” So while the making of the film garnered the ire of the upper-caste locals, the film itself was in fact “a subversion of the casteist system.” In Abraham’s narrative, Vigathakumaran becomes a smashing hit immediately after its release in 1930, but Rosy is threatened and abused to the peril of her life and is forced to make heartbreaking choices to save her family from the violence perpetrated by the upper caste goons who attack her home. [caption id=“attachment_8854071” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The English translation of the original Malayalam renders an engrossing narrative of Rosy and Daniel’s journey of creating the first-ever Malayalam movie in history.[/caption] Through the English translation, Arathy and Venkiteswaran poignantly capture Rosy’s predicament, blending in seamlessly the cultural milieu of Kerala in the early 1900s with the first filmmaking experiences of the Malayalam cinematic community. For her part, Arathy opines that considering the socio-political circumstances of the time, Rosy’s decision to work in the film was a revolutionary act. Rosy hailed from a small community of grass cutters but “she moved beyond lines set for her by society by the sheer power of the artistic grace inside her.” And the price she had to pay for that was a steep one.

“She had to run away from her hometown, change her name and live the ordinary life, away from the world of art. Till her death, she never acted again.”

The translator remarks that it was Venkiteswaran who roped her into the process of writing an English translation of Nashtanayika and this was the first time that she read the fictionalised account of Rosy’s story. Before that, she had simply heard about “PK Rosy as one of the women pioneers in cinema.” The book, however, “cut the road into Rosy’s life, in more ways than one,” she continues, it highlighted “the socio-political economic conditions of the time, and thus also set off how brave was the action initiated by Rosy.” Venkiteswaran and Arathy worked separately on different chapters of The Lost Heroine, but Arathy notes, “I often called up Venkity to speak to him on the regional references in the story, for example, the Kakkarassi plays. It was important to know the various art forms and about how Rosy got initiated to the world of cinema.” Speaking about taking Abraham’s narrative effectively into English, Venkiteswaran notes, “I think it is all about the process of translation; some sort of transmigration takes place as you enter the text prising it open with another language and try to wade through the twists and turns of the writer’s words, and the thoughts and actions of the characters. It generates a flow in and through you that takes you along.” He continues, “It was also an interesting experience of translating with Arathy, as, in some instances, I found certain other kinds of resonances in her journey through the text, so the translation of Lost Heroine was a jugalbandi of sorts.” What is most striking and heartbreaking about the novel is Rosy’s contemplation, after she is no more an actor, after Daniel has moved away from cinema, after the dream they envisioned together is destroyed in the mayhem that follows the film’s release. In these chapters, Rosy is breathes new life, not as a Pulaya girl from Thayyacaud but as a heroine, as the heroine of Vighathakumaran and it is only in the one surviving tape of the film which is in Daniel’s house that she is immortalised. “Rosy. The girl who lives as Sarojini, whom Rosy gave life to, in the movie called Vigathakumaran. The girl who lives in the reels of the cinema called Vigathakumaran that lies drowsily in the green painted square box placed in a corner of this veranda.” Vinu Abraham’s The Lost Heroine, translated by CS Venkiteswaran and Arathy Ashok has been published by Speaking Tiger

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)