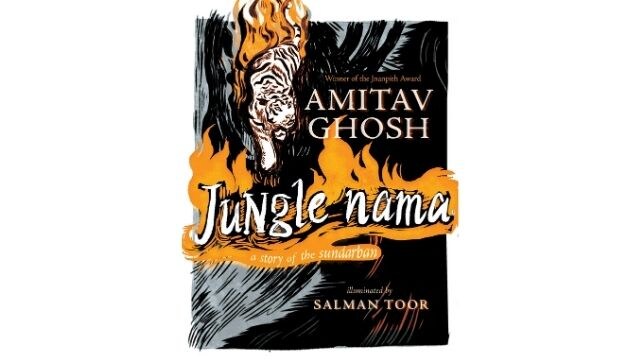

On a Zoom call with Amitav Ghosh who joins me from New York, he seems exceptionally at home talking about the Sundarbans, which is where he finds himself yet again in his new literary venture Jungle Nama, a book of verse in English, adapting the legend of Bon Bibi, the presiding guardian spirit of the wetlands in the east. The term ‘Bon Bibi’, literally translating to “lady of the jungle”, is an unmistakable nod to the syncretic socio-religious structure of her homeland and place of worship, as the honorific “Bibi” stems from Islamic culture — a sobriquet widely adopted by Muslim women. Daughter of a Sufi dervish, Bon Bibi is nominated by Allah as the vanquisher of the evil Dokkhin Rai (literally meaning “lord of the South”), an affluent landowner who haunts the wilderness and shape-shifts to prey on innocent villagers in the guise of a tiger. Bibi, instead, chooses to subordinate Dokkhin Rai and orders him to protect her disciples, failing to do which would lead to harsh punishments. Following this legend, people across the region, irrespective of their religion, have worshipped this unique Bengali goddess for decades and have evoked her to safeguard themselves and their lands against unknown perils lurking in the wild. Ghosh’s unwavering loyalty towards the Sundarbans, therefore, is legitimate, even if unsurprising, as the terrain instinctively commits itself to storytelling. “The Sundarbans is a very powerful landscape, you know. It just works its way into your head, so that you can’t escape it even when you want to,” he tells me, only to immediately draw my attention to the anomaly of the shockingly derisory amount of literature, even in Bangla, that has been written on its terrifying beauty. He can barely fathom the reason behind this obvious discrepancy. “For example, when I started writing my last book Gun Island, initially, I didn’t intend to start it in the Sundarbans. But somehow, it just happened. The Sundarbans itself pulled me back into the landscape, so that I had to engage with it. Clearly, it just keeps pulling you back,” he laughs. His award-winning 2005 novel The Hungry Tide traversed the wide expanse of the mangrove jungles, immersing itself in its culture and ecology through sumptuous prose that has gone on to hold immense sway on urban, English-speaking Bengal’s imagination in the years that followed — a telling assertion of which can be found very close to his South Kolkata home, where a chain of restaurants is named after the book. It also triggered significant curiosity in the Sundarbans itself, as Ghosh testifies by saying that he continues to meet people who have confessed to “visiting the Sundarbans after reading the book”. With Jungle Nama, he hopes to accomplish this feat again. This time, Ghosh goes a step further and engages with Sundarbans’ popular folk cultures that allegorise man-animal relationships and conflicts, which form the crux of the landscape’s very existence. He, however, does not strictly adhere to either of the two printed iterations of the legend — both written in Bangla and titled Bon Bibi Johuranama (‘The Narrative of Bon Bibi’s Glory’), by Abdur Rahim Sahib and Munshi Mohammad Khatir — composed in the 19th century. “The curious thing about the texts is that their first half is actually on Bon Bibi’s life in Saudi Arabia — about her life in Medina, about her parents, the father who is a fakir, her stepmother and mother. Those are long sections in the story which are interesting, but not as interesting to me as the story of Dhona, Mona and Dukhey [three of the human protagonists in the lore whose episode Ghosh captures in Jungle Nama],” he says, adding that he decided to focus on this particular segment because it is an environmental story. “It is a story about finding balance with the world. In most stories told by indigenous peoples or Adivasis or forest peoples everywhere, not just in India but also in the United States — they focus a great deal on this concept of ecological balance, and how do you not take everything away from the earth. But, if you look closely, stories like this in English hardly exist. I felt that there is a great moral urgency at this particular moment in time (for such stories), when we really are facing an ecological catastrophe, as we saw with this Uttarakhand disaster,” Ghosh says. As a writer — and not an activist or politician — the only thing he believes he can do is “produce stories which actually sensitise people, if you like, in some way”. [caption id=“attachment_9296941” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Jungle Nama has been published by Fourth Estate, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.[/caption] While the moral lesson underlining the tale cautions readers against unbridled avarice, the focus is unequivocally on the environment and its pressing concerns. “If you think, there are so few stories that parents can actually read to their children that are about this idea of finding balance with the world. So I felt it was very necessary, in that sense, to have a story like this that could be introduced to them,” he says. Jungle Nama, in that regard, could prove to be an intellectual treat for the bookworm across age groups, as the verses almost caper through the pages with a spring in their steps. Ghosh employs the Bengali verse meter dwipodi poyar (loosely translated as ’two-footed line’) which is unique to literature written in the language — comprising rhyming couplets — along with hybrid words, in an earnest attempt to reproduce the accurate essence of the originals, which had generous helpings of words with Persian and Quranic Arabic influence, as the writer mentions in the afterword. This, in turn, inspires community reading and collective interaction with the text, which happens to be an inherent part of lore culture and evolution. According to the writer, it might even be the need of the hour. “I feel it is very important that stories like this be created in a way that they are not books that are only read by individuals. So the Bon Bibi Johuranama, or if you take our Mangalkabyo — they are all written in chhondo (rhythm or prosody) and poyar. If you read the Mangalkabyo, you will see that any long stretch of the poyar is actually accompanied by a raga. They were always meant to be performed; they were meant to be heard, read aloud and that too collectively. This is another very important aspect of the reading experience that we have to reclaim,” Ghosh says. “This whole idea of reading in the silence of our own heads — we have to move away from that. We have to try and find ways in which reading itself is collaborative. So, it was very important for me right from the beginning that this book be written in verse and chhondo. The poyar meter, in my mind, is perfect for narration,” he says — and justifiably so, as is evident from the great volumes of lyrical work composed in poyar in Bangla that read almost like novels, despite being purely in verse. Ghosh, however, has a bone to pick with Indian writers and publishers of mythology, who are snubbing the verse and reiterating and retelling epics in prose — an uninspiring, even lazy disservice done to their rich poetic legacies that inherently lend themselves to performance. In Jungle Nama, the meter-rhyme scheme constitutes the magic in the tale, both literally and figuratively, as the characters (rather meta-narratively) refer to and use it while beseeching the jungle goddess for help. The poyar itself is an important character in the story. But in a pandemic-ridden world in 2021, how does the author imagine a society transcending their screens to engage collectively in storytelling and reading? “I wrote in my book The Great Derangement that the crisis that we are facing today really calls for collective responses. A lot was happening at the start of 2020 — there were these youth movements led by Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion (UK) that were really getting underway. And then the pandemic happened, and suddenly we are all hyper-individuated, stuck in our rooms with our devices,” he tells me. However, Jungle Nama’s very foundation is based on collaborative effort on multiple levels. “As soon as you have the book in your hand, you are already looking at a collaboration because of the marvellous artwork done by Salman Toor. I think Salman is really one of the most talented artists of this generation; the ways in which he was able to translate the imagery into these magnificent icons is incredible. The moment you have that book in your hand, you are not in a space of words — you are in a space of images, which take you to another place.” The striking artwork by Toor in black, white and hints of grey leaps off the sheets and catches one off guard; the deep shadows and spectral shapes animate the images, lending them a peculiar flickering quality that allows the reader to get transported into the depths of the marshes they depict. As a result, the places and characters not only come alive, but acquire a frightening tactility despite being elusive — like optical illusions birthed by the forest’s tenebrosity. The artist, undoubtedly, packs quite a punch with this one, as the visuals independently claim and establish their space in the book, telling their own story while buttressing the verses they interact with. No wonder Amitav chooses to refer to them as “illuminations” as opposed to ‘illustrations’, as the latter often tends to convey that images are merely ancillary to the printed word. [caption id=“attachment_9296951” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Salman Toor. Facebook/yael.drazninblumberger[/caption] “One of the things that modern culture has done since a few years now is that it has created this completely logocentric approach to the world, where the text dominates everything, and where slowly iconography and imagery are treated as secondary. That is why this word ‘illustration’ is so often used. It implies that you’ve taken a bit of text and put a picture on it. I didn’t want to do that at all,” he tells me. Traditionally, as the writer points out, Indian texts like the Bhagavata Purana, Razmnama (Persian translation of the Mahabharata, commissioned by Akbar), Shahnama, or even the palm-leaf manuscripts are all “illuminated” texts. Ghosh, however, knew right at the outset that ‘illuminating’ the tiger would prove to be a challenge, but Salman’s “uncanny talent” left him “bewitched” more often than not. “One day, he just sent me this image, and it was so arresting. The way that he has visualised the tiger and has it spread out on the page…it’s just so arresting! It arrived one night, and I just caught myself staring at it for hours. And this happened repeatedly. Salman’s is no ordinary talent.” This exquisite collaboration has been followed by another delightful liaison with Pakistani writer and singer Ali Sethi — a former student of Ghosh’s at Harvard University — who is the narrator of the Jungle Nama audiobook. “He is a rigorously trained classical singer, but he also knows how to translate the classical idiom into contemporary sound. So he was absolutely perfect for this project. It’s like a ragamala — he is going through certain ragas right now like Ahir and Bhairav. I am sure it’ll be a very successful audiobook,” Ghosh says, visibly excited at the thought. [caption id=“attachment_9296981” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Ali Sethi. Facebook/ali.sethi.98[/caption] In a bid to uphold and celebrate indigenous storytelling traditions, Ghosh wishes to diversify and explore mediums like the graphic novel and even video-gaming for Jungle Nama in the days to come. “I want this to exist in multiple iterations like it happens in folklore, which exists as jatra, as dance, as puppetry; I want all of that,” he says. While the graphic novel is still at a very nascent stage, his son — a gaming enthusiast — has already developed a visual language for the video game. “It would be the opposite of the standard game, because the idea in this game would be that he who is not greedy, wins. So it would have to be structured on opposite principles, where co-operation is rewarded, as opposed to the usual game where the individual winner is rewarded. So maybe it would have to be structured as a counter-game,” Ghosh thinks aloud. Clearly, the writer revelled in verse-writing, which he considers an “exercise of the brain muscles” as it involves using intellectual tools that lie mostly unused and forgotten. “I think humans are born with the capacity to versify, but since verse is so undervalued in contemporary life, that aptitude is completely neglected. That’s why rap music is so popular, because it’s a way of versifying. Once you versify, you literally realise that you use a dimension of language that is practically dormant.”

At the end of the day, however, Jungle Nama is really about sustaining folk traditions that are devised to empower and give a voice to the non-human. “The non-human voice is the one that modern literature has completely suppressed. In every culture, everywhere, the non-human used to have a very powerful voice which has now disappeared. Our literature has become completely human-centred and increasingly urban,” Ghosh says. Wistfully, he reminisces of a time when Bengali writers, even a generation ago — like Mahasweta Devi and Adwaita Mallabarman — would extensively write about country life. “But if you look at contemporary Bangla literature, it is so very centred on cities and city life. It’s the same, whether it is in English or in Bangla. But stories earlier would be about storms, floods, famines, tidal waves — all the things that people have had to deal with in the Indian past, especially in the past of the Bengal delta, which is so very tied in with rivers and flooding, and so on.” His words remind me of a conversation during a particularly dire period in recent Bengal history — as recent as last year — when Cyclone Amphan barrelled through the state in the middle of the pandemic in May 2020, leaving the Sundarbans to cushion its heaviest blows, as has been tradition. While visiting one of the worst-hit pockets of the delta only days after the calamity had struck, I had chanced upon an octogenarian who told me that they often wear masks with Dokkhin Rai’s face on it at the back of their heads, as a talisman, to ward off predators in the dark when they venture close to the tiger reserve. “But even Dokkhin Rai’s face couldn’t save us from this murderous cyclone,” he said. Evidently, lore and fables, as Ghosh argues, are more than just stories for the societies they are born into — they hold the ecosystem together by functioning as a crutch for survival on some days, and a way of life on some others. Jungle Nama by Amitav Ghosh has been published by Fourth Estate, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)