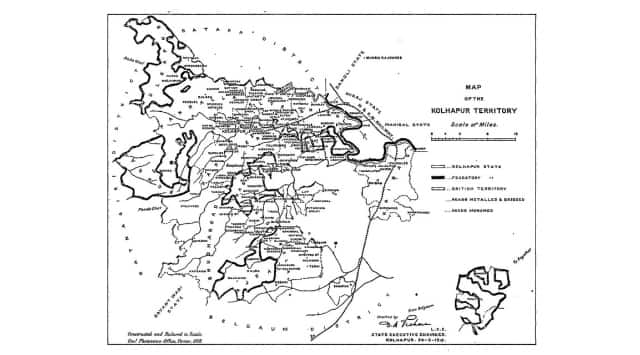

In 1882, political affairs in the present-day state of Maharashtra witnessed an unusual meeting of minds. Mahatma Jotiba Phule, the social reformer and trenchant critic of caste Hindu practices and the caste system, spoke up for ‘Lokmanya’ Bal Gangadhar Tilak and his associate, Gopal Ganesh Agarkar. Tilak wasn’t a fan of Phule’s critiques, as his own beliefs veered towards the orthodox. In that sense, Phule’s views were directly ranged against Tilak’s. So, how had this come about? The occasion was the conviction of Tilak and Agarkar in a defamation case involving the Dewan of the Kolhapur princely state, Mahadev Barve. The issue at hand was the alleged mental illness of the ruler of Kolhapur, Shivaji IV. In the Maratha universe, Kolhapur was not just another princely state. It held a special place owing to its direct connection with Chhatrapati Shivaji. (Satara was the other kingdom that had been founded by another branch of Shivaji’s descendants.) The Kolhapur kingdom had been established in Panhala by Maharani Tarabai, Shivaji’s daughter-in-law, the wife of his younger son, Rajaram in 1710. And so, there was more than a passing interest in its affairs across the region. But a series of complicated adoptions and the extended periods of regency on account of them had resulted in influential nobles and others dominating the rulers. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, attention came to be focused on the then ruler, Shivaji IV and his ‘madness’, as put forward by Barve and backed by the British. Tilak and Agarkar publicly questioned the diagnosis, treatment and mental state of the Chhatrapati. The Kesari, under the editorship of Agarkar, and the Mahratta under Tilak, both argued that Shivaji IV was not ‘mad’ and that his fragile mental state was on account of the maltreatment given to him by the servants and officials appointed to take care of him. They accused Mahadev Barve, the British appointed Karbhari (Chief Administrator) of Kolhapur, of complicity in the conspiracy to make Shivaji IV mad. Mahadev Barve then filed a defamation case against Tilak and Agarkar. Tilak and Agarkar’s comments were in large part motivated by their desire to take on the British. In court, however, the duo were found guilty and sentenced to four months imprisonment. It was at this juncture that Phule now stepped in to speak up for them. He was touched by the fact that two Brahmins (Tilak and Agarkar) had stood up for a non-Brahmin ruler (the Kolhapur royals were Maratha by caste). This triggered off a close relationship between Tilak and the Kolhapur royals, which continued under the next ruler, Shahu, who ascended the throne in 1894. On Tilak’s suggestion, Shahu helped the Shivaji Club, who undertook revolutionary activities, with money and weapons. But in 1899, this relationship came undone. And set the stage for a momentous decision at the beginning of the 20th century. [caption id=“attachment_9824611” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Shahu Chhatrapati seated with palace servants. Image via WikimediaCommons[/caption] The Vedokta Controversy ‘Vedokta’ refers to Vedic religious rites which are supposedly the right of all the twice-born castes (Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaisyas), as opposed to the ‘Puranokta’ (from the Puranas) rites which all Shudras were entitled to perform. The controversy arose on account of the contested Kshatriya status of the Marathas, who formed the bulk of the ruling families in Maharashtra, northern Karnataka and the central India region (the Scindias of Gwalior, the Gaikwads of Baroda, the Holkars of Indore, the Bhosales of Satara and Kolhapur and several other ruling houses were all Marathas). In 1896, the Gaikwad of Baroda had staked his claim to Vedokta. In 1899, Shahu did so as well. His royal priest, however, refused to oblige him since Shahu, in his view, was a Shudra. While Shahu was, of course, incensed, he was not alone in his attempt to contest the ruling of the Brahmins. Other Maratha royal houses backed him and soon, things snowballed into a Brahmin versus non-Brahmin fight, with the Marathas contending that the Brahmins were trying to pit one royal house against the other. On this issue, given his orthodox views, Tilak took the side of the Brahmins, though with a caveat — he was willing to concede Vedokta rights to Shahu not because he was a Kshatriya or because the Marathas were Kshatriyas, but because he was a Chhatrapati. This ‘halfway-house’ was not to Shahu’s liking. And to accept it would have been to let down the other royal families as well. Owing to this and also due to the mood of the time — a number of social reforms to questionable Hindu practices had already been undertaken by then — Shahu took a momentous decision. On 26 July 1902, Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj of Kolhapur issued a historic proclamation. 50 percent of the posts in the state’s services, he decreed, would be reserved for the backward classes. It was the beginning of what came to be called ‘reservation’ or ‘affirmative action’. The Brahmins who dominated the administrative class were severely affected by this move. Tilak, in his editorials in the Kesari termed this move undiplomatic and immature and wondered if Chhatrapati Shahu had lost his mind. Far from it, Shahu’s move was well thought through and influenced heavily by his background and upbringing and the variety of experiences he had undergone by this time. [caption id=“attachment_9824621” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Kolhapur State Map, 1912. Image via WikimediaCommons[/caption] Chhatrapati Shahu Shahu was born in 1874 in the ruling family of Kagal near Kolhapur. Originally named Yashwantrao Ghatge, he was adopted into the Bhonsale dynasty and became the ruler of Kolhapur in 1894. Educated at Rajkot’s Rajkumar College, Shahu travelled extensively in Europe and India, besides interacting with reformers and thinkers like Mahadev Govind Ranade, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Gopal Ganesh Agarkar back home. He was also a trained wrestler, and his legendary strength inspired many anecdotes. It was said that he could take on a bear or a tiger unarmed. In 1898, he had operated a water wheel that was usually pulled by four oxen. Clearly, he was made of sterner stuff than many of the royals of the time, who backed off from confrontation. Having made the first move towards social justice with his reservation notification, Shahu went even further. In 1911, he initiated free education for children from the depressed classes (roughly equivalent to today’s Scheduled Castes). In 1917, he made primary education free and mandatory for every child in Kolhapur state and implemented this law, as the evidence shows, both in letter and spirit. In 1917, when primary education was made free and compulsory, Kolhapur had only 27 schools with 1,296 students. By the time he died in 1922, Shahu Chhatrapati had helped build 420 schools which admitted more than 22,000 students. In 1919, the Legal Sanction to Inter-caste and Inter-religion Marriage Act was passed, as was the Law for Prevention of Cruelty against Women and the Manifesto against Observance of Untouchability. Clearly, Shahu was committed to the welfare of the backward classes and also to the idea of a modern, forward-looking society that was modelled on what he had observed in Europe. And it had all begun with the 1902 reservation ruling, a bold and unusual move which predated British India’s and independent India’s moves in this direction.

On 26 July 1902, Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj of Kolhapur issued a historic proclamation. 50 percent of the posts in the state’s services would be reserved for the backward classes. It was the beginning of what came to be called ‘reservation’ or ‘affirmative action’.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)