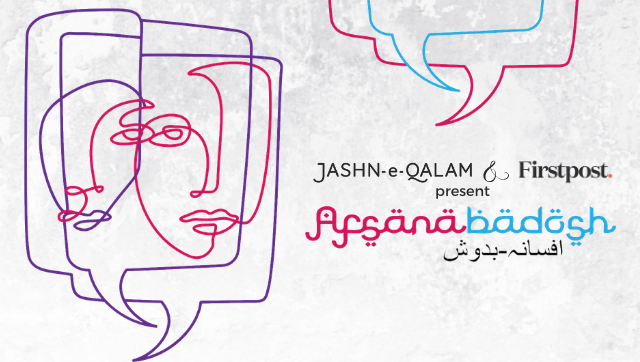

Editorial support, execution and text by Neerja Deodhar | Art by Pinaki De | Episode edited by Varun Patil AFSANABADOSH afsana (story, legend) | khanabadosh (vagabond, gypsy) AfsanaBadosh is the coming-together of stories and a vagabond perspective to traversing the world of fiction. It is embodied by the sort of person whose head is always in a book, or who looks for stories in the places they visit and people they meet. But it is not that cliche of an old man with a long, white beard who trades in legend and cannot rest in one place. AfsanaBadosh is us: ordinary individuals who have experienced the beauty of storytelling in different contexts — as a way to better know the world, to find a sense of solace, and to enrich and entertain. It speaks to an ability to listen to and contend with ideas different from our own; to learn from the past and build a better future. AfsanaBadosh is Firstpost and Jashn-E-Qalam’s celebration of the spirit of storytelling through narrations of fiction written by some of Hindi and Urdu’s greatest writers. These include Rajinder Singh Bedi, Saadat Hasan Manto, Mannu Bhandari, Krishan Chander and Premchand. The stories that are part of this project have been chosen for their continuing social resonance, decades after they were published. The foundation of each story is a sense of truth, whether real or imagined. Episode 6 — Salam Bin Razzaq’s ‘Kamdhenu’, as performed by KC Shankar. Listen to more episodes here . *** SALAM BIN RAZZAQ made his literary debut soon after graduating from school, with a short story in the magazine Shayar. Decades later, he would go on to win the Sahitya Akademi Award for his Urdu short story collection Shikasta Buton Ke Darmiyan. Apart from writing in Hindi and Urdu, he also translates works written in Marathi. He retired as the principal of a school run by Mumbai’s municipal corporation. In 2013, he was the recipient of the prestigious Ghalib Award. Ordinary people and the circumstances they cannot escape are the subjects of Razzaq’s fiction. “The ordinary man cannot be expected to fight like a hero. He must compromise if he has to survive, but his compromise is not surrender," he once said . Many of his stories are also an examination of communalism. At the same time, he draws literary inspiration from religious texts like the Ramayana and Mahabharata. *** The image of the KAMDHENU, rooted in mythology, is associated with plenitude. She is the cow of plenty, the divine bovine-goddess, the very embodiment of sustenance and sacrifice. To venerate any cow in India is to honour the ideal of the Kamdhenu. And cow worship is no joke in our country. Neither is the weaponisation of the cow in the country’s politics — whether in electoral politics, or through bans on beef, or cow vigilantism. This is what makes the image central to Razzaq’s story so powerful — that of a cow belonging to a cowherd, who is milked repeatedly without so much as giving the cowherd notice, let alone asking for his permission.

Razzaq begins this story with a description of the village of Bharatpur: the natural beauty of its fields, the sound and image of dairy animals, cowherds and milkmen who reside there. He describes the many festivals and religious rites that take place within this small village, which has an integrated population of both Hindus and Muslims. What is common to people from both religions is the practice of dairy farming and bovine keeping. Bharatpur is unique in that it has never been witness to communal violence. It is not that the people of this village are closed off to news of riots and tumult outside, but that their own hearts and minds are not moved by such social divides. When fights did take on a communal colour, they were resolved swiftly. The tranquility of the village is disrupted by the jarring presence of jeeps, rallies and political party flags. It is election time in the village, and the air is filled with proclamations from loudspeakers, about worthy political candidates and their agendas. Jeeps carrying these candidates and their many supporters capture the attention of every single Bharatpur resident. Turab Ali is among the first politicians to visit the village, appealing to the villagers’ sentiments as cowherds. He invokes his faith and identity, drawing vague connections to their livelihood, trying to make himself seem like one of them. He completes this charade by declaring that he will milk a cow. The entire village waits with bated breath to know whose cow will be chosen for this purpose. Ultimately, it is the one who stays in the unadorned house of Madhav, a cowherd who lived even beyond the Harijan settlement. Madhav is dumbstruck at first when Turab Ali arrives at his door. When the situation is explained to him, when he is told that his fortunes will change if his cow is milked by Ali, he becomes even more dazed. He wanted to turn down this offer, since he’d milked the cow just that morning. He wanted to shake his head to express this. But he was a man who had spent his whole life nodding along to things said by men more powerful than him. Almost as a reflex, he nodded, instead of saying no. What followed was a spectacle: Turab Ali preparing to milk the cow with great fanfare, a stool and pail appearing out of thin air, and people climbing walls to watch the scene. Ali thanked Madhav for letting him milk the cow, to prove his connection to cowherds. Madhav wanted to object, but there was no opportunity for him to express himself. The events of the morning repeat themselves a few hours later, only the politician and his identity change. Pandit Omkarnath, the son of another pandit who built an ostentatious temple, is the next candidate to campaign in the village. He claims to be the voice of the people, and representative of the culture and traditions of India. He says that he has a true connection to the villagers, and that roots cannot be built only by milking a cow, unlike what his competitor tried to portray. Like Ali, he invokes faith and religion, tracing the identity of cowherds today to Krishna himself. As is typical of the kind of politics we see today, where those who claim to be ’native’ or ‘indigenous’ Indians try to ‘reclaim’ Indianness from ‘outsiders’, Omkarnath decides to milk the same cow as Ali. Reclaiming the cow is synonymous to reclaiming the country; he even ‘purifies’ the cow before getting down to business. A third politician, Baburao, tries to create the same spectacle for a third time, claiming a stronger connection to cowherds because of his socioeconomic status. He turns the milking of Madhav’s cow into an issue about respect and dignity. For the first time, Madhav objects, but no one pays heed to him. The cow gives milk to whoever milks her. She validates the identity of those who claim to be cowherds, or have connection to them. She wordlessly becomes part of whatever political agenda she is framed within. But her wounds and trauma are only for her and the cowherd to deal with. By himself and in conjunction with the cow, Madhav signifies both religion and ordinary Indians — such is the genius of Razzaq’s craft, that his metaphors are multifaceted. In a country where religious strife and discrimination is an everyday affair, employing religion to win votes is an inevitability. People’s faith, arguably a personal matter, is turned into a poll issue, and the ability to ‘protect’ or ’nurture’ or ‘represent’ religion becomes a marker of capable leadership. What is lost in the bargain is social harmony, rational thought and scientific temper. Madhav’s predicament also mirrors that of citizens who are rushed to political rallies, offered promises of development, even non-consensually featured in government ads, to sell the idea of a certain political party — only to be abandoned and forgotten once election results are announced.

)