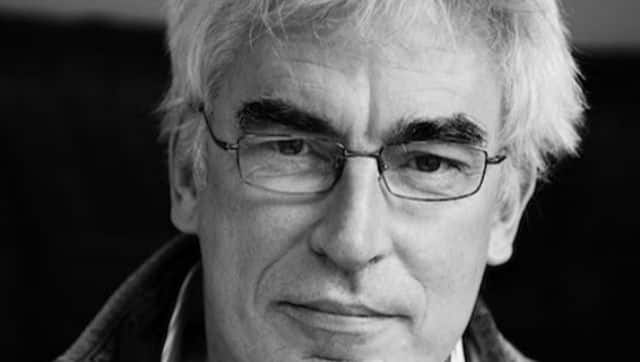

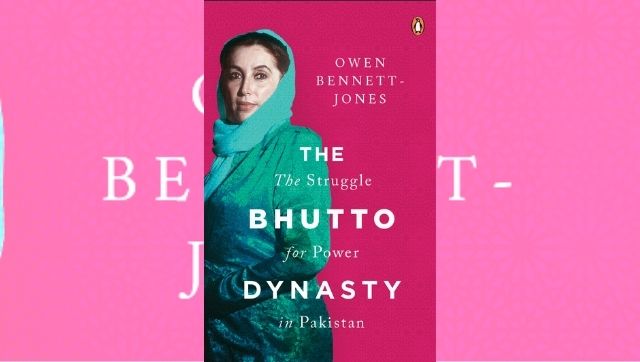

In The Bhutto Dynasty_, author and journalist Owen Bennett-Jones brings forth an investigative narrative that explores the legacy of this influential family from Pakistan and its turbulent political journey. Chronicling the life of the astute politician Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his political rise, along with that of his four children, the book draws from unpublished documents and research accumulated over two decades to tell the story of the family’s complex relationship with British colonialists, the Pakistani armed forces and the United States of America._ The steep political rise of the patriarch Bhutto and the equally dramatic fall which led to his execution in the late 1970s, the assassination of three of his children, most recently that of the two-time Prime Minister of Pakistan, Benazir Bhutto, in 2007 are all recorded in Bennett-Jones’ work, making it a simultaneously compelling and insightful reading of politics in Pakistan and the history of one of its most illustrious families. The excerpt that follows traces this family’s history, its long lineage that goes back 12 centuries to their Rajput ancestors, their mixed heritage and their move to the Pakistani province of Sindh. *** [caption id=“attachment_8988701” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Author and journalist Owen Bennett-Jones chronicles the legacy of the powerful Bhutto family in his latest work, The Bhutto Dynasty. Image via Twitter[/caption] Among the many documents hidden away in the Bhutto family library in 70 Clifton, Karachi, is a family tree commissioned over fifty years ago by the dynasty’s most famous son, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. It traces twelve generations of Bhuttos, but the dynastic story really goes back twelve centuries to a time when the Bhuttos’ ancestors were Rajputs, a warrior caste that became the most important Hindu ally of successive Moghul emperors, providing them with military forces. The Rajputs were composed of tight-knit, disputatious clans, and it is from Rajput culture that the Bhuttos inherited some enduring traits, such as a willingness to embrace confrontation in defence of personal honour, placing a high degree of value on owning land and, until the advent of Benazir Bhutto, the practice of keeping the family women covered and secluded. Occasional references to the Bhuttos’ ancestors in various seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Rajasthani chronicles confirm their Rajput heritage. But details are scarce, and the story is complicated by confusions between Bootas, Bhuttas, Bhuttos and Bhattis, and some inter-marriages between them. The latest research suggests that the Bhattis (and many Punjabis still bear that name) are a distinct genealogical line, while the Bhuttas and Bootas are the ancestors of the Bhuttos of Pakistan: in many cases an ‘a’ at the end of family names changed to ‘o’ as part of the process of colonial anglicisation. Over the centuries, however, many Rajasthani and Western historians, and even family members, have conflated these different groups, making it hard to disentangle who was doing what, where and when. Lieutenant Colonel James Tod in his 1920 Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan described a ninth-century Bhatti prince who ruled an area around Tanot, now an Indian town near the Pakistan border. The prince arranged for his son to marry the daughter of the chief of the Bootas. In the first of many colourful tales about the family’s internecine competitiveness, bold strokes and ambition, Deoraj, the son of the Bhatti/ Boota union, asked the Boota chief for a village in which to settle down. The chief offered some remote desert land, the size of which was described by the area that could be encompassed by thongs cut from a single buffalo’s hide. When Deoraj built not just a home but a castle on the site, the Boota chief sent a force of 120 men to destroy it. However, Deoraj tricked the assailants, inviting them in groups of ten into his castle before murdering them. Deoraj’s action is the first recorded episode of the Bhuttos’ unceasingly dramatic dynastic story, although that’s not to say that a direct line can be traced between him and the Bhuttos of Pakistan. But from time to time Bhutto ancestors appear in various Rajasthani histories, and often in prominent roles. According to the Gazetteer of the Bahawalpur State 1904, for example, the Bahawalpur town of Bhuttavahana was named after the Bhuttos when they won control of it around 900 AD. The earliest known artefacts relating to the family are two stone pillars engraved in Sanskrit which to this day can been seen standing in the open near the Indian city of Jaisalmer in Rajasthan. The oldest, over 2 metres high, was erected in 1148 under the instruction of a queen, Naikadevi, who is described in the carving as having been born a Bhutta and married to a Bhatti. A second pillar dated 1173 also mentions ‘the renowned Naikadevi’, whom it describes as a pious devotee of a Sarva, a belligerent god who killed with arrows. Naikadevi, the inscription says, worshipped the arrow, and, although there is no evidence that he was aware of the precedent, nearly 800 years later Zulfikar Ali Bhutto chose that symbol for his Pakistan People’s Party. That Naikadevimarried a Bhatti indicates that at that time – the twelfth century – the Bhuttos were still Hindu. It’s not clear when they converted, but family folklore suggests it was during the seventeenth century – much the same time as the branch that went on to govern Pakistan moved from Rajasthan to Sindh. According to one of the present-day elders of the Bhutto family, Ashiq Bhutto, some of the Bhutto homes still contain remnants of the family’s Hindu heritage, such as traditional Hindu wedding clothes, although they are now in tatters. ‘Even when I got married some aspects of the ceremony were what the Hindus do, Hindu tradition,’ he said. Why the Bhuttos moved is unclear. One family story talks about a feud between different branches of the family. Another has the Bhuttos’ forebears aligned to Dara Shikoh, the Sufi-minded brother and rival of the Moghul emperor Aurungzeb. According to this version, passed down orally through the Bhutto generations, a branch of the family had picked the wrong side, and when Aurungzeb had Dara Shikoh executed in 1659 they were forced into exile and moved to Sindh. Despite being Hindus, the Bhuttos had started taking an interest in Sufi Islam – which is suggestive of a link to Shikoh – and began visiting shrines, thereby starting a process that led eventually to their conversion. The man who appears to have led these geographic and spiritual shifts was Sehto Bhutto, who settled near the village of Ratodero, close to Larkana in what is now the Pakistani province of Sindh. It was an area in which vast hunting grounds afforded space for newcomers to settle and prosper, and it may be that political disruption in the area meant that the existing occupants had been forced to move. However they got hold of the land, Bhuttos have been there ever since. As he settled in Sindh, Sehto Bhutto would quickly have become aware that there were three groups who mattered in his new home area: the tribes, the religious leaders and the landowners. His most pressing priority was to build good relationships with Sindh’s tribal rulers. At the time, as Moghul power declined, Sindh was undergoing a period of some turbulence, and various groups tried to fill the vacuum. Eventually the Kalhoras, described by an early British colonial historian as ‘a tribe of fighting fanatics’, became dominant but in 1783 they were toppled by another tribe, the Talpurs, who held sway until 1843 when they were defeated by the British. Sehto and his descendants had to pick their way through these significant political changes. The above excerpt from Owen Bennett-Jones’ The Bhutto Dynasty has been reproduced here with permission from Penguin Random House.

Chronicling the life of the astute politician Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his political rise, along with that of his four children, the book draws from unpublished documents and research accumulated over two decades to tell the story of the family’s complex relationship with British colonialists, the Pakistani armed forces and the United States of America.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)