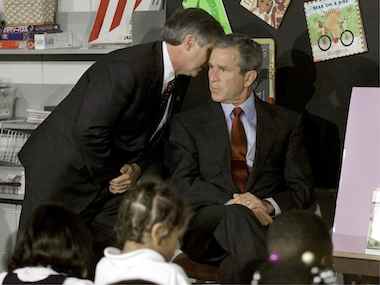

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from Avirook Sen’s Looking For America (Harper Collins 2010), a brilliantly observed travel memoir that paints a witty, insightful portrait without resorting to the usual preconceptions and stereotypes. In this episode, Avirook Sen visits the now famous preschool where President Bush first got the news of the attacks. His experience reveals a nation and its people grappling with 9/11’s bitter legacy: recession, budget cuts, war, and ever-present paranoia. ‘We are what is called a school in need of improvement,’ said Ms Marya Fairchild, assistant principal of Emma E. Booker Elementary in Sarasota, scene of a still famous video featuring George W. Bush. [caption id=“attachment_81142” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“U.S. President George W. Bush listens as White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card informs him of a second plane hitting the World Trade Center REUTERS/Win McNamee”]  [/caption] This is where, on 11 September 2001, the president got the news that commercial planes had been flown into the Twin Towers. He was, as some people might recall, listening to second graders reading ‘My Pet Goat’ at the time. (There is a controversy over whether he had his own copy of the book upside down, but let’s not digress.) In the minutes before he heard the attacks had taken place, President Bush heard the words ‘get ready’ repeated over a dozen times. But it wasn’t Dick Cheney speaking into his earpiece—it was the teacher orchestrating a reading performance by the kids as the president promoted his recent ‘No Child Left Behind’ (NCLB) legislation. Seven years on, it turned out that not just one child, but the whole school had been ‘left behind’. Booker Elementary remained a ‘C’ school, whereas every other school in the county is rated ‘A’. ‘Think of it like a trajectory,’ said Ms Fairchild, ‘we’re not on the path to meet requirements.’ How could Booker Elementary meet requirements? It was a ‘neighbourhood’ school in the town’s roughest neighbourhood. ‘If you were to pull out a demographic report by this zip code, my guess is that this area would have the highest crime rate in Sarasota,’ said the prim assistant principal. The school had 537 kids, 94% of them were from the (mostly black) minorities and 91% lived below the poverty line. To get to it, you passed places that sold ‘soul food’ on the outside and drugs on the inside. You crossed shacks and shanties and bums and cats. And, of course, a railway line. This was where most of Booker Elementary kids lived. Here, you could find every reason why the Republicans flunked Florida. People were wary of four more years of the same. A lot of them blamed the war for everything. For instance, couldn’t the poorly funded NCLB programme have benefited greatly from a fraction of the $10–12 billion monthly war bill? Ms Fairchild had taught history at the Booker Middle School, to which a number of kids from the elementary school ended up going. I asked her whether she taught any of the kids who were there in the classroom when President Bush visited on 11 September 2001. She said she didn’t recall the event having come up with any of her students. And then, quite suddenly, she refused to take any more questions. The interview was over. She told me to get in touch with the school board for more information. I stepped outside into the parking lot and was in the middle of a call to Gary Leatherman at the board’s communications desk, when a police car pulled up next to me. It had been less than five minutes since I left the school building. Deputy Perrin from the sheriff’s department asked me how I was doing—and what I was doing. He then told me the reason why he asked this: ‘Someone called saying a guy was roaming around the campus—with a bag.’ This was true. I was carrying a (rather cool, if I may say so) blue laptop bag. I told him I had just been inside and spoken to the assistant principal. He said he’d better go and check. A few minutes later, he found me again at the head of the road. As he pulled up, another cop car arrived. Deputy Scott had been sent over as well. Perrin asked for my passport and diligently began entering its details into the computer in his car. He told Scott that I was asking about 9/11. For a brief moment I didn’t hear that right and was about to say that I didn’t call 911 (the emergency number) when I realized that someone from the school had. Fantastic. The conversation went as follows. Scott to me: You don’t have any weapons or anything, do you? Me laughing somewhat nervously: Certainly not. Scott to Perrin: You patted him down yet? As Perrin kept working with my passport, Scott started another round of questioning. Knowing that anything I said might be held against me, I told him the whole truth and nothing but the truth. I was there because George W. Bush was in one of the classrooms on the campus on 11 September 2001. Scott’s badge said he’d served the department since 1994. He went on, ‘Oh, I was there that day. Spent anxious hours, traffic blocked all over the city. The president could have been a target. We had to get him out of here.’ I was thinking, well, the president was probably safest around here. The guys who executed 9/11 had been based close by, a few months previous to that day, training at flight schools in Venice, Florida, but they’d reportedly left by August. On 9/11, President Bush was safer at Booker Elementary than he would have been at the White House, which was a definite target. Meanwhile, in Venice, where Ziad Al Jarrah trained in order to hijack Flight 93, which crashed in Pennsylvania, Arne Kruithof was still in business. When I went to Venice and called Kruithof’s school, Florida Flight International, he was unavailable. But a well-spoken lady said he would call back. Fat chance. The man had been at the centre of conspiracy theories ever since the ‘smiling’ and ‘helpful’ Al Jarrah trained under him in 2000. But he still ran his school and, according to reports, still trained people hostile to America for a perfectly sensible reason—these countries also bought aircraft and needed to transport people. Not every Iranian or Saudi was a terrorist. But if you were from the sheriff’s department, it was worth checking. After all, Iran and India would both be in the ‘I’ folder on the database. Deputy Perrin finally completed the data entry and said that his colleague required a photograph of me. I was, of course, the picture of cooperation. So, right below the sign that said Booker Elementary, I posed for the snap. I called a cab after the shoot was over and my passport safely in my bag. Deputy Scott asked me where I was headed next. I told him that I was bound for Orlando, then on to Alexandria, Virginia; Toledo, Ohio; Chicago, Illinois; Madison, Wisconsin; and parts of North Dakota. ‘Man,’ he said, ‘I wish I could travel like that. But I’m stuck here.’ He was. On a patch across the street, till the time my cab arrived. Protecting the kids at Booker Elementary. And I, with depressing visions of now being on a suspects’ database which said ‘must strip-search’ at every airport, headed back to the familial warmth of the Sunshine Motel.

Avirook Sen visits the now famous preschool where President Bush first got the news of the attacks. His experience reveals a nation grappling with 9/11’s bitter legacy: recession, budget cuts, war, and ever-present paranoia.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by FP Archives

see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)