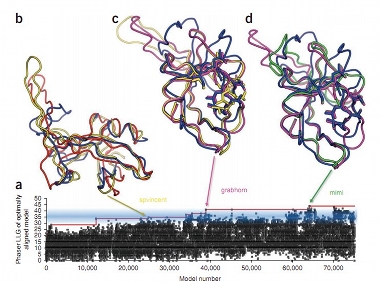

Players of an online game called FoldIt have unravelled the structure of an protein that causes AIDs in rhesus monkeys that has eluded scientists for 15 years. Their discovery, which took teams of players just three weeks, has been confirmed by x-ray crystallography. The virus which causes AIDS in rhesus monkeys is called Mason-Pfizer Monkey Virus and its protease is very similar to that produced by HIV. A fuller understanding of its structure could eventually lead to drugs to treat these diseases: Knowing the structure of the enzyme allows scientists to look for potential drug targets, or areas of the molecule to which a drug could attach and prevent it from working. Once the enzyme has been neutralised, the virus can no longer spread. The protein in question is a ‘monomeric protease enzyme’. In HIV it breaks down viral proteins in order to reassemble them into a new ‘coat’ for the virus. Many HIV drugs work by inhibiting this enzyme, preventing the virus from getting a new coat, maturing and replicating. Whilst enzymes can be viewed through a microscope, that only gives a 2D representation of its structure. In order to find possible targets, researchers need a 3D model which can be unfolded and rotated. This is where FoldIt comes in. [caption id=“attachment_87365” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“Models from three users, SPVincent, Grabhorn and Mimi, evolve from left to right.”]  [/caption] Teams of players collaborate to tweak a molecule’s model by folding it up in different ways. The result looks somewhat tangled, but each one is scored on criteria such as how tightly folded it is and whether the fold avoids atoms clashing. The structure with the highest score wins. Anyone can play and most of the gamers have little or no background in biochemistry. Although there are computer programs which try to model protein structures, humans are far better at it, as Seth Cooper, one of Foldit’s creators, explained:

“People have spatial reasoning skills, something computers are not yet good at. Games provide a framework for bringing together the strengths of computers and humans. The results in this week’s paper show that gaming, science and computation can be combined to make advances that were not possible before.”

The paper was published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology yesterday and is also available online from the University of Washington (PDF). The figure above shows how the starting model, the red squiggle in (b), was developed by user SPVincent (yellow). It was then further refined by Grabhorn (magenta) and Mimi (green) over a period of 16 days. This isn’t the first time that citizen scientists have helped make discoveries. In 2007, Dutch school teacher Hanny van Arkel discovered a strange green object in the constellation of Leo Minor while she was participating in astronomy project Galaxy Zoo. And a 2009 paper by the Galaxy Zoo team included the name of Rob Proctor, a volunteer who worked on their merging galaxies project. As the number of citizen science projects continues to grow, so do the opportunities for non-scientists to engage in serious scientific work. This latest discovery could play a key role in the development of treatments for AIDS, but as citizen science projects show more success, this is likely the first of many discoveries that ordinary people like you will make.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)