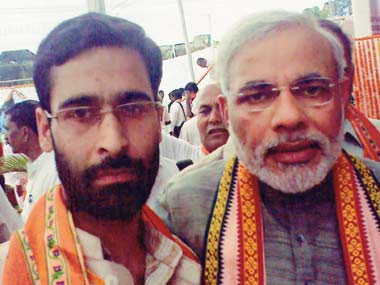

by Sameer Yasir On a bright Sunday morning in early May, more than one hundred BJP workers gathered in the courtyard of a palatial maroon-coloured house in the Mominabad locality of Anantnag in south Kashmir. Ashiq Hussain Dar, 29, the tall, bespectacled vice-president of BJP’s youth wing in Kashmir silently watched his colleagues speak from the podium. The BJP workers had gathered to assess their preparation for the 2014 Assembly Elections in Jammu and Kashmir. As Ashiq rose from his seat to address the gathering, there was thunderous applause - a sign of his popularity among the workers. But then he did something unusual for a Kashmiri politician, even one from the BJP. He began his speech by heaping praises on Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi and made a case for adopting his economic policies in the state. Suddenly there was pin drop silence. [caption id=“attachment_804911” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Modi with Ashiq Hussain[/caption] Ashiq told his colleagues that the media was only portraying a negative image of Modi and that no one talked about his style of “visible development”. “Modi is the man who changed the economic status of common Gujaratis,” Ashiq said. “Be it Hindus or Muslims, he will change this country when he becomes the Prime Minister.” The gathering gave him a patient hearing and eventually, a loud applause. Despite the cheering crowd of BJP workers however, Anantnag is no longstanding bastion for the party. The town was once the hotbed of separatist militant fighting forces in Kashmir valley. In those years, forget Modi, no one dared to take even the BJP’s name openly here. In his carefully worded speech, Ashiq avoided talking about the controversy of 2002 Gujarat riots which still hangs over Modi. Ashiq says it is a big issue but the CBI and courts have exonerated Modi. Ashiq has been publicly praising Modi ever since he met him at a BJP party meeting in Mumbai. “He hugged me and told me about the development which has happened in Gujarat. He told me that with better economy, every conflict washes away,” Ashiq remembers. Ashiq’s political journey started from the extreme end of the political spectrum in the Kashmir valley after the 1989 armed conflict. He joined the Muslim Conference in 2005, a Hurriyat breakaway faction led by Ghulam Nabi Sumjhi who is an executive member of Syed Ali Geelani-led Hurriyat Conference. Around that time Anantnag was still a haven for insurgents. To quell the militancy, the government renegades “used to do whatever they liked” recalls Ashiq. “They would take the daily earnings of people. That is what forced me to join politics.” Ashiq says he joined the Muslim Conference to fight daylight extortion by government renegades, but felt he could not do much to bring about change. He soon left the party and joined Mulayam Singh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party (SP) instead as District President Rural in 2006. But he was disappointed there as well. “For them Kashmir was not a priority,” he says. In October 2006 he met Narendra Modi in Mumbai which was when he decided to join the BJP. He says he was convinced by then that regional parties were not powerful enough to motivate the powers in Delhi to engage in real political dialogue. Ashiq believes having the same national party in power in both Delhi and Kashmir at the same time could work wonders for Kashmir. “The Kashmir problem can only be solved by BJP. It needs a Narendra Modi style of governance. If he becomes the Prime Minister, he would definitely change the situation in valley, like Atal Bihari Vajpayee had almost managed to do,” he says. But not everyone in his own party has the same faith in Modi. A senior BJP leader told a rally that Modi’s election to the top post would send a bad massage to the common people. “Although he is a very popular leader of our party I think there are better leaders like Sushma Swaraj and Arun Jaitley who can become good Prime Ministers. Making Modi the PM would be an unpopular decision,” says one senior leader who did not wish to be named. Aftab Ahmad, a third year BA student of Amar Singh College in Srinagar, says if Modi becomes the prime minister, it would send the wrong message in a democratic country like India. Ahmad recently traveled to different cities in Gujarat as part of a student exchange program organized by an NGO. He admits the reality is complicated. “Although, as the head of the state, Modi is responsible for the massacre of Muslims in 2002, the reality today is Gujarati Muslims vote for Modi too,” he says. But Ahmad also feels that the question of who gets the top gaddi in Delhi doesn’t matter that much to Kashmiris, because the national issues that preoccupy Delhi “hardly matter here”. However Ashiq is not alone in his support for Modi. At a recent rally against spurious drugs carried out by the BJP’s state unit in Srinagar’s historic Lal Chowk, many party workers carried pictures of Narendra Modi. Although no regional political party in Kashmir, including the BJP’s former ally, supports Modi openly for the post of Prime Minister, no one wants to come on the record with their own prime ministerial wish list either. In many ways, Ashiq’s open support for the three-time Gujarat chief minister symbolizes a political shift in Jammu and Kashmir. “People think that with the kind of development-dream Modi was able to realize in Gujarat, he might manage a similar miracle everywhere after becoming Prime Minister. But running a state is something and managing a country is something else,” says economist Nassir Ahmad. The rise of the BJP in Jammu and Kashmir is interesting. Kashmir has been ruled mostly by National Conference since the conflict broke out in early nineties. The only exception to its rule was when PDP and Congress cobbled together a coalition government, but that didn’t complete its six-year term. Before the 2008 Assembly elections the BJP was represented by a lone member in the state legislature. During the 2008 Kashmir unrest the party blocked the supply of essential commodities to Kashmir by erecting barricades on the National Highway after the controversial decision by the then Congress government to transfer a piece of land to the Amarnath Shrine Board. The move earned them the sympathy of voters in Jammu who had felt sidelined during the crisis. The party won 11 seats. In Kashmir valley, more than 25,000 votes were polled in favour of the BJP. Going by the aggressive campaign it has launched, the party clearly hopes to also open its account in Kashmir valley in the coming assembly elections. That’s where Modi becomes a gamble. Fielding him as a prime ministerial candidates could mean the risk of losing some of the ground the BJP has gained in the Valley. On the other hand, Modi at the helm could actually galvanize voters in Jammu. Either way one thing is clear. Politics is changing in Kashmir says Gull Mohammad Wani, director of Kashmir Studies Institute. “It is also possible that people are fed up with the regional parties. But it is not only BJP but many other national parties like Samajwadi Party who have fielded as many candidates as regional players,” says Wani. Last year when Rahul Gandhi visited the University of Kashmir, he was surrounded by hundreds of admirers including young students of the university. So one thing is clear – the two stalwarts of Kashmir politics, the National Conference and the PDP have competition these days from the national parties. “As the situation improves in the Valley, it won’t be a cakewalk for the two regional parties (National Conference and PDP),” says Wani.

Ashiq Hussain Dar is an oddity, even for a BJP leader, in Kashmir. He openly embraces Narendra Modi saying only he can bring change in the state. But his own colleagues are more reticent.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by FP Archives

see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)