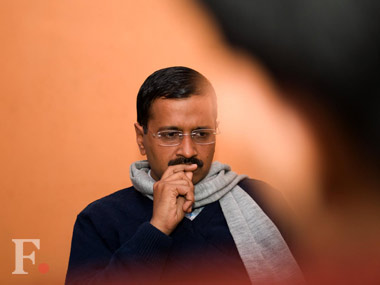

In December 2012, members of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), met at the Indian Social Institute, New Delhi. Among other subjects on the agenda, they wanted to discuss the issue of leadership: who will spearhead this newly formed party?Three months had passed since India Against Corruption – the group which conducted the Jan Lokpal crusade – announced its decision to enter politics. Anna Hazare, the social activist who led the movement, declared his opposition to the move and refused to be associated with the Aam Aadmi party. AAP needed a new leader. [caption id=“attachment_1170495” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  AAP Convenor Arvind Kejriwal. Naresh Sharma/Firstpost[/caption] “We decided to give the party a face people could relate with. Since Arvind Kejriwal was the second most recognisable personality of Jan Lokpal movement after Anna Hazare, he was the obvious choice of all the members,” says Prithvi Reddy, member of AAP’s national executive council who was present at the meeting. When Kejriwal was consulted, he initially resisted the move, claims Reddy, “When forced, he said he was OK with it if that was the unanimous decision.” Almost a year later, however, AAP has become synonymous with Kejriwal. In the nation’s capital, AAP has consistently projected the former Indian Revenue Services officer as the panacea to all the ills faced by the city including corruption, inflation and crime. The party has many prominent figures – former TV journalist and RTI activist Manish Sisodia, senior lawyer Prashant Bhushan and psephologist Yogendra Yadav – who contribute equally as Kejriwal to the party leadership in their own capacities. But it is Kejriwal who monopolises the limelight, as when he went on a hunger strike in a resettlement colony in North East Delhi to protest inflated water and power tariffs; led street gherao of the chief minister’s residence; leveled corruption charges against political leaders and corporate houses. In the run up to the assembly election, it is the face of an angry Kejriwal, representing the frustration of the aam aadmi, which dominates party banners across the city and on the back of the omnipresent auto rickshaws. And it is Kejriwal who is positioned as a potential giant-killer, poised to take on the reigning three-term chief minister Sheila Dikshit in her constituency of choice. The focus on Kejriwal has drawn criticism from observers who argue that AAP is turning into a personality based party. “The campaign is increasingly centered around Kejriwal, and the AAP sometimes seems to be less a mass movement than a cult around an individual,” noted Santosh Desai in The Times of India. Thus, despite the presence of an array of leaders, it is difficult to imagine AAP minus Kejriwal. According to Arvind Kejriwal, such perception is less an outcome of party efforts than media focus. “This is the way media has projected it,” he told _Firstpost. “_The party has many spokespersons, but reporters continue to approach me for quotes and sound bytes. At times, I have refused to comment. On those occasions, they simply don’t carry any comment.” Big personalities have always dominated electoral politics in India. The Congress party’s leadership is defined by the Gandhi family – and thrown up strong oppositional figures who rebelled against their hegemony. Jayaprakash Narayan, for example, galvanized the youth in challenging the Congress regime when Indira Gandhi imposed emergency in the country in 1975, birthing the ‘J P movement’. Despite its relatively democratic structure, BJP too has been defined by singular leaders, be it Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Lal Krishna Advani, and now Narendra Modi. And regional parties are inevitably one-man or one-woman shows, be it the Bahujan Samaj Party (Mayawati), Janata Dal United (Nitish Kumar) and AIADMK (J Jayalalitha).“All over the world, personalities have come to play an important role,” says Yogendra Yadav. But aren’t such personality politics contrary to a party that challenges the high command culture and presents itself as a democratic alternative? No, says Yadav, as long as a leader is selected on merit and he remains accountable to party members. “If the person becomes accountable only to himself or herself, then that can be a problem. Also, the proportion one is given outside need not necessarily be the proportion one gets inside the organization,” he said. Abhay Kumar Dubey, political scientist and faculty member at Centre for Study of Developing Societies, Delhi agrees: “Projecting someone as a leader is not undemocratic in itself. How do you function without a leader? What is important is that how the leader emerges and what happens to other voices in the party after his emergence.“Rise of Narendra Modi within the BJP, according to Dubey, is a classic case where one personality suddenly rises over others and is able to silence other voices in the organisation. “This does not hold true for AAP,” he argues. “People mobilize around a symbol and they vote for leader. This is no contradiction or oxymoron,” says fellow political scientist Jai Mrug. So far, the AAP is riding high on brand Kejriwal. It is trying to cash in on his clean image and popularity in the national capital. But the party will have to search for a new face if it wants to expand beyond Delhi. “In rural Karnataka, for example, the party would have to identify someone local who people could relate to. Many of them might not know Arvind,” said Prithvi Reddy.

The focus on Kejriwal has drawn criticism from observers who argue that AAP is turning into a personality based party.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)