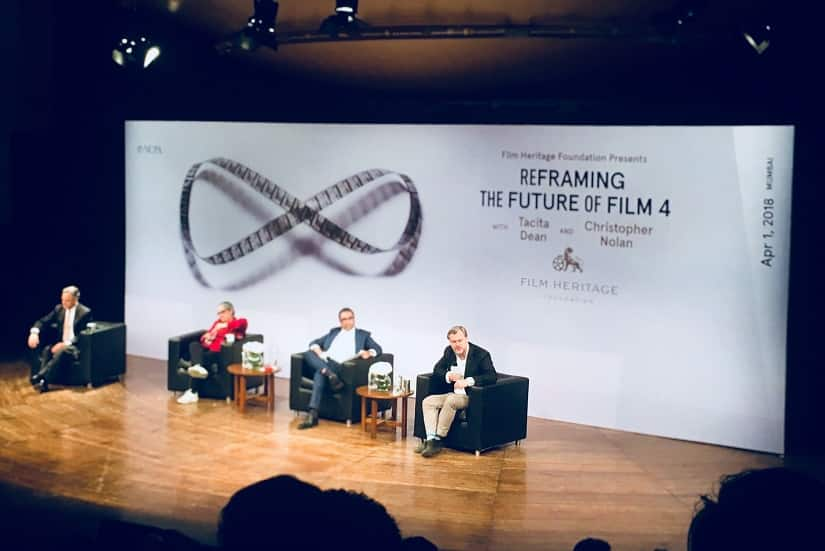

For a man whose time seems so precious, Christopher Nolan doesn’t give the impression of being in a hurry. There’s a measured elegance to his response to every question — ones that range from the deep to the absurd. Yet, every time he speaks, what you unequivocally take away from his words and his demeanour (once you’re accustomed to his quite-British wryness) is his unbridled passion for the art and craft of film and cinema; yes, the two mean different things. Speaking at the National Centre for Performing Arts (NCPA), at the closing event for the ‘Reframing the Future of Film’ series held by Film Heritage Foundation, Nolan minced no words when quizzed by moderator Shivendra Singh Dungarpur about whether his insistence for shooting on film (when most filmmakers the world over have moved to the digital format) was a matter of nostalgia. “Nostalgia is the term they use to dismiss someone’s passion,” was Nolan’s instant reply. [caption id=“attachment_4414939” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Christopher Nolan in Mumbai. Firstpost Photo/Sachin Gokhale[/caption] Through the event, Nolan helped shed light on how the digital medium may be more popular today, but it can never match up to the imaging quality of photochemical film, be it in terms of the image-capturing process or in the projection of those images. This, he says, is one of the key reasons why he shoots on celluloid, and prefers it when his films are consumed by the audience through film projection itself. Read on Firstpost: What Bollywood filmmakers can learn from Christopher Nolan during Dunkirk director's India visit Film, of course, has almost completely been phased out as a medium for cinema, because of the purported advantages that supporters of the digital format claim the latter has. One of these is convenience, in terms of the size and nature of the cameras. Intuitively, you’d think that this would apply in particular to the large-format cameras that Nolan used extensively in Dunkirk and Interstellar. These cameras are large, cumbersome and are loud during operation, because of the spinning film reel. While there are those who feel that such cameras are intrusive and distracting to actors, particularly while shooting close-up scenes, Nolan has a different take on it. “I find that film cameras help the actors focus, because they can literally hear the money spinning away,” he quipped, his answer amusing the audience, because of how it slyly took on another criticism that the film format draws — the cost of film itself. Yet, Nolan did indicate that the cost of shooting on film shouldn’t be a factor for filmmakers, because of the many advantages that shooting and projecting on film has over digital. Even in terms of storage and archiving, while digital has many proponents, Nolan pointed out that digital isn’t the most cost effective way of storing cinema. (Indeed, digital technologies tend towards obsolescence quite soon, and often without warning. There is no one reliable format in which files can be stored — hard disks tend to crash, and high quality film footage needs large storage space, which can be quite expensive. Film, on the other hand, can last for hundreds of years if it is stored in appropriate conditions.) Nolan also made pertinent points about how film and digital are, in fact, two different media, which means that filmmakers who shoot on digital should be exploring the format to innovate and do things that you can’t do when shooting on film. [caption id=“attachment_4414913” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Christopher Nolan at the Reframing the Future of Film event in Mumbai on Sunday, 1 April. Photo courtesy Firstpost/Pradeep Menon[/caption] When asked by an audience member on how young independent filmmakers can shoot on film, Nolan gave the example of American filmmaker Sean Baker, who made the world’s first feature-length film to be shot completely on the iPhone. While the film, Tangerine, saw a theatrical release in the US in 2015, Sean Baker went on to direct 2017’s acclaimed The Florida Project, which he primarily shot on 35mm film. From our archives — Dunkirk: Why India can't watch Christopher Nolan's IMAX war epic the way he intended This, Nolan said, is a prime example of how the digital format can be used by young filmmakers to establish their credentials as storytellers, before they graduate to using film as a richer medium to tell their stories cinematically. Visual artist Tacita Dean, who was on the panel for the group discussion, agreed with Nolan on how film, by sheer virtue of it being a physical medium upon which an image is imprinted, instantly becomes a more real and valuable form of capturing an image, as opposed to the abstract, intangible pixels and binary code that comprise a digitally captured image. Undoubtedly, his unwavering belief in the superiority of film puts Christopher Nolan in a very small minority, even if others of his ilk include the likes of Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson. With prolific filmmakers like Steven Soderbergh and David Fincher (both of whom are older and have a larger body of work than Nolan) swearing by digital, Nolan’s stance on film might be seen by many as being antiquated. Yet, what he brings to the argument with his love, passion and understanding of the film medium, combined with the proof of the pudding — the sheer joy of experiencing his films in his preferred format — are perhaps the reason why Nolan stands apart as a beacon for those enamoured by the magic of film.

“Nostalgia is the term they use to dismiss someone’s passion,” was Christopher Nolan’s reply when asked if his insistence for shooting on film (when most filmmakers the world over have moved to the digital format) was a matter of nostalgia

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)