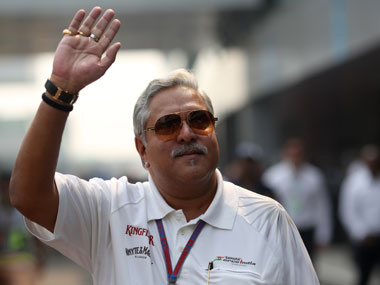

The courts seem to be coming to the aid of crony capitalists as much as politicians and other vested interests. For the third time in as many months, court orders have come in the way of banks recovering dues from some of their major defaulters. It is precisely the ability of the legal system to delay action against defaulters that helps crony capitalism alive – where loans are repaid only if a project is profitable, but if it is not, they may remain un-repaid forever. The wayward borrower pays no penalty for leaving behind bad loans for the taxpayer to clean up. Last week, the Calcutta High Court struck down United Bank of India’s (UBI’s) order of May 2014 declaring Vijay Mallya, and three of his former directors on Kingfisher Airlines, as ‘wilful defaulters’ – a tag which effectively debars them and all the company boards they hold positions on from accessing further bank loans. While UBI can remedy its process and seek a modification of this order, the fact is there will now be further delays. To be sure, it is possible that UBI did not get all parts of its legal spadework in order. But the court order, delivered by Judge Debangsu Basak, gives what seems like lightweight reasons for striking down the wilful defaulter tag. [caption id=“attachment_2020447” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Reuters image[/caption] According to Business Standard, the court struck the UBI decision down because the panel declaring Mallya a wilful defaulter had four members instead of three! This is what order said, according to the newspaper: “The (UBI) identification committee held a meeting on May 22, 2014, to identify constituents as wilful defaulters. It was constituted by four members - one executive chairman, a chief general manager and two general managers. This is in excess of the number of three personnel prescribed in regulation 3(i) of the master circular on wilful defaulters issued by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). In such circumstances, the decision arrived at by the identification committee is a nullity. Consequently, all steps taken by United Bank of India subsequent to such so-called identification are also a nullity. Significantly, the grievance redressal committee also comprised four members. This is also in violation of regulation 3(iii) of the master circular issued by RBI.” Sure, UBI seems to have tripped over a minor aspect of the regulations, and the bank's bosses will surely remedy these faults . But, surely, having four members decide on identifying who is a wilful defaulter means more care was taken before the declaration was made than if only three members did so? If a technicality is going to delay a lawful action, should courts be a party to such delays? Where it suits them, the courts have, in fact, gone out of their way to interpret laws in favour on some party or the other – but in this case they have allowed a mere technicality to delay things. In October, a Supreme Court bench rejected the State Bank of India’s first right to collateral on Rs 3,000 crore of loans to sugar mills, saying the money must first be used to pay cane growers. Chief Justice HL Dattu effectively junked the State Bank of India's legally valid collateral on the principle that the right to life (of growers) supersedes the right to business. But was it the banks who were denying growers the right to life? The State Bank merely lent money to sugar mills. It was the inability (or unwillingness) of the mills to pay growers the state government-fixed prices for cane which was the cause of any denial of dues to farmers. The blame for endangering the farmers’ right to life either lies with mills or the state government. And yet, it was the bank that got penalised. Any sugar mill owner will thus know that he can delay payments to cane growers, and expect banks to pick up the tab. Then, when it comes to repayment, the banks will willy-nilly have to reschedule their loans to avoid having to declare them as bad. If this is not an unintended benefit to crony businesses, what is? In another judgment, the Supreme Court decided that when it comes to loan recoveries, the provisions of the Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985 (SICA), will be given priority over the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 (RDDB). As we noted before , under a key SICA section (section 22) a company gets protection from all creditors while a revival plan is in the works. However, under the RDDB, which is also a special act intended to aid debt recoveries, section 34 allows lenders to recover their dues from defaulters even if other laws gave some succour to the borrowers. By deciding that SICA will prevail over RDDB, the court has effectively encouraged attempts by businessmen who won’t want to repay loans to seek the protection of SICA to ward off their creditors. In the Arihant Threads case, which is where the Supreme Court held that SICA provisions will be given priority over RDDB, the debt recovery was not stayed due to a technical delay by the management. But the implications of the judgment are that managements can rush to the Board for Industrial and Financial Restructuring IBIFR) under SICA to avoid repayments. The only way to get over this problem is to correct the intentions of the law. It is worth mentioning that the Arihant loan was given in the early 1990s, and an order of the Debt Recovery Tribunal in favour of the bank was obtained in 2003. It has taken 11 more years to get the courts to say the money can be recovered. Court-induced delays, despite the existence of laws to expedite recoveries, will effectively warm the cockles of crony capitalists who never intend to repay bad loans. It is time the courts woke up to their larger responsibilities to ensure that taxpayer money invested in public sector banks is not used to come to the aid of cronies.

The Calcutta High Court rejected the UBI’s decision to call Vijay Mallya a wilful defaulter on a technicality. If courts are going to go by mere technicalities to delay banks from recovering their dues, only crony capitalists will celebrate

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by R Jagannathan

R Jagannathan is the Editor-in-Chief of Firstpost. see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)