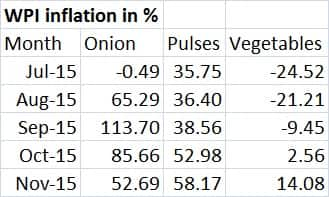

The inflation picture until March is getting clearer. And it certainly does not look good for the rate cut- lobby. The sharp spike in inflation numbers released on Monday — both the consumer price index inflation (CPI) and Wholesale Price Index inflation (WPI) — had one common factor — a worrying spike in food inflation, mainly in the prices of pulses. It has to be remembered that pulses are probably the only source of protein intake for India’s rural households, which cannot afford costlier egg and milk products. [caption id=“attachment_2504922” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Representational image. Reuters[/caption] The CPI inflation, the key price indicator of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for policy purpose, rose to 5.41 percent in November, from 5 percent in the preceding month. The food inflation rose to 6.07 percent from 5.25 percent, vegetables rose by 4 percent compared with 2 percent and that of the pulses zoomed by 46 percent compared with 42.8 percent. The food inflation is likely to stay high through the March-quarter on account of two reasons. One, the benefit of base effect has clearly vanished (On a lower base last year, inflation will show a higher jump in the corresponding period this year even though the quantum of increase remains the same). Two, the unseasonal rains is feared to impact the rabi sowing.  The picture portrayed by November WPI numbers was not too different. The overall food inflation in WPI basket rose to 5.20 percent in November from 2.44 percent in October. Of this, prices of pulses, onions and vegetables showed the biggest spike with pulse prices shooting up by 58.17 percent in November on year, while onion prices rose by 53 percent and that of vegetables 14 percent. The spike in rural inflation has outpaced urban inflation citing rural price pressures, points out Radhika Rao, economist at Singapore-based DBS Bank. Rural inflation in November quickened to 5.95 percent compared with 5.5 percent in October, outpacing urban at 4.7 percent (vs October’s 4.3 percent). “The sub-components also revealed a stronger run-rate in the former (rural), apart from food. This divide will add to the central bank’s calls for the government to ease structural bottlenecks to ensure a pass-through of the benefits from low commodity prices/ food costs and improve rural infrastructure to calm rural price pressures,” Rao said. The RBI has acknowledged the problem of persisting high food inflation in its latest monetary policy announcements, even when it has drawn comfort from the decline in overall inflation. Part of the reason for the negative WPI is the plunging crude prices besides the slowdown in global markets but the reason why it is not reflecting on the food and vegetable prices is the fact that it is more of a supply-side reason. This would also mean that monetary policy has no big role to play in dealing with this problem. Besides the nearly stagnant growth in pulse production for several years, dealing with failed monsoon in consecutive years compounds the problem. RBI’s challenge The RBI under Raghuram Rajan has already cut its key lending rates by 125 basis points so far this year, including a higher-than-expected 50 basis point cut in September. It paused in the December policy citing inflation concerns. The central bank has an inflation target of 5.8 percent in January and a medium-term target of 5 per cent. Most economists believe that the 5.8 percent target is achievable, but find the medium-term target of 5 percent challenging. This is no good news for the rate cut lobby. The high food and pulse inflation would significantly curtail the available room for Rajan to effect further rate cuts at least in the first quarter of calendar year 2016. “Chances of any more monetary easing in this fiscal are almost zero,” said Devendra Kumar Pant, Chief Economist at India Ratings & Research. “Pulses inflation can pose a threat to fight against inflation and mainly instrumental in pushing retail in the month of November.” Secondly, a possible lift off in US rates this week would mean that the RBI’s leeway to tinker with rates is further limited. The US Federal reserve is sure to hike rates sooner or later if it perceives pick up US economic growth. The bottomline is this: It is increasingly becoming evident that India’s inflation problem, mainly in pulse prices, are primarily on account of increasing supply gap and not a demand-driven one and the solution lies with the government (measures to improve supply and prevent market distortions), not the RBI (read here ). But one thing is for sure, the current rate spiral is inflicting more pain on the rural India than it does on people in urban centres. (Kishor Kadam contributed to this story)

One thing is for sure, the current rate spiral is inflicting more pain on the rural India than it does on people in urban centres

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)