By Aditi Roy Ghatak and Paranjoy Guha Thakurta

In the first and second parts of our story on the mispricing and misallocation of spectrum since 1994 (read here and here ), we showed how telecom operators were officially given a certain amount of spectrum, but in reality got twice that amount. But this unintended benefit was given not just by one regime, but several of them ranging from the Congress government of the 1990s to the NDA at the turn of the century.

* * * * * * * * *

On 30 January 2011, a group of academics submitted a commissioned report to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (Trai) on “The 2010 value of spectrum in 1,800 Mhz band”. It was clear that the entire pricing of spectrum had become so convoluted (in all probability, deliberately) that there was need to get a fair fix on prices with retrospective effect, though the exercise was not described as such.

There was much confusion about what would be a fair price for spectrum and whether third generation, or 3G, auction prices of 2010 could be treated as a fair price for 2G. The experts were hard at work estimating the cost of spectrum that had already been sold by the government. Had it not been a matter of such gravity, this might have occasioned some hilarity.

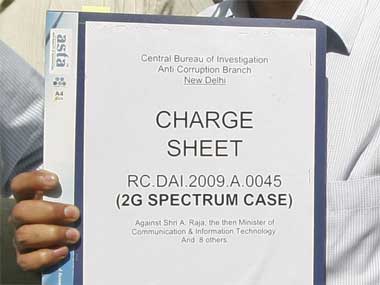

[caption id=“attachment_327075” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“For the record, the government issued licenses for cellular mobile services for Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai under a duopoly (not more than two cellular mobile operators for each circle)”]  [/caption]

Impact Shorts

More ShortsNevertheless, in the world of the Mad Hatter’s Telecom Party, a DoT chart (prepared by these experts around May 2011), said that the 2001 entry fee per Mhz of spectrum was Rs 27.53 crore in Delhi - dividing the entry fee of each LSA (licensed service area) by 6.2 Mhz. In 2010, it was Rs 149.78 crore per Mhz up to 6.2 Mhz and Rs 249.73 crore beyond 6.2 Mhz. Most of these experts have been consultants to the powerful DoT though it is not suggested that they were less than totally above board.

The group was not asked to travel back beyond 2001 and did not visit 1994-95, when the spectrum scam started. As one has already noted, even the Justice Shivraj Patil Committee, which produced a monumental report on the developments in the Indian telecom space, did not go into the spectrum scam that took place before 2001. Industry sources question the methodology followed by these experts, who have themselves asked for more time to review their report.

What has not been investigated is if the earliest beneficiaries of the spectrum allotments received a bounty in excess of 35 Mhz. It would be a good idea to get these experts to extrapolate what the generosity of the government cost the exchequer (using 2001 figures) in 1995. In any event, Trai itself says that the valuation makes several significant assumptions and eventually the figures estimated by the experts “may not always match the exact market price”. More importantly, it is suggested that these are undervaluations, which will become a sensitive issue if (at all) and when the operators are charged for any excess spectrum they hold.

Industry sources say that one way of deriving an estimation of the value of the extra spectrum would be to add to the price of the additional spectrum a percentage of the value at which the beneficiary companies sold their equity. Indeed, the current crop of ‘guilty diluters of equity’ is not the first one. Amongst the first ones were Bharti and Hutchison! Indeed, C Sivasankaran of Sterling Cellular sold out to the Essar group in 1994 for a reported $150 million, according to George Hiscock, writing in India’s Global Wealth Club. Essar later sold its interests to Vodafone.

Meanwhile, Sivasankaran bought the RPG group’s Chennai mobile phone services in 2003 for about $60 million that he later sold to Malaysia’s Maxis group for a little over $1 billion. These numbers are indicative of the sums for which telecom companies in India that had access to spectrum could change hands even in those early days.

The critical question is whether and how the recipients of the government’s largesse leveraged the value of the excess spectrum to build (for some) their not-too-substantial capital bases in those times. It occasions little surprise that the suspected spectrum giveaway has been brushed under the carpet. Exposing it to public scrutiny would mean being forced to learn from the first scam so that the exchequer could be protected from being looted any further. Today the loot continues.

As one finds the octogenarian Sukh Ram, in whose regime all this started, shifting residences between prison and hospital, it would be of interest to know what was the actual nature of the scam that he had unleashed, which is entirely different from the one for which he lost his portfolio and found himself in handcuffs. The estimated loss to the exchequer for the detected scam was about Rs 1.7 crore, which is small change compared to the ongoing loot. (See Chart A and Chart B on India’s telecom ministers and secretaries)

The most important reason to revisit the origin of the telecom scam is that the spectrum giveaways - for which Sukh Ram was never charged - never got detected or discussed. The minister and his bureaucrat, then Deputy Director General (Telecom) Runu Ghosh, have since been sentenced to imprisonment in another case featuring the award of a contract to the Hyderabad-based Advanced Radio Masts (ARM) for telecom equipment. The charge was that the company, whose Managing Director P Rama Rao is also serving a three-year jail term, charged the DoT a higher rate, causing the exchequer a loss of around Rs 1.7 crore. For the bigger scam, the former Union minister has not even been investigated.

The long arm of the law took a rather long time to mete out justice to the perpetrators of the fraud. The ARM scam occurred in 1993, the trial court ordered a three-year jail term for the minister and the managing director in 2002; the order was upheld by the Delhi High Court on 21 December 2011 and confirmed by the Supreme Court on 5 January 2012.

Meanwhile, the spectrum giveaway has been given a quiet burial; the actual loss to the exchequer is yet unassessed. More worrying is that the theft continued through the next phase of the liberalisation of India’s telecom sector.

Under the New Telecom Policy (NTP) 1994, DoT had also cleared the technical portion of the 158 bids that it had received from 32 companies for nationwide cellular services. These covered 20 state circles that had not yet been opened up for licenses. There were no bids for the troubled North-East or for Jammu & Kashmir and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. The government, thereafter, issued 34 licences for 18 service areas (two licences were issued for Cellular Mobile Telephone Services, or CMTS, in 16 areas and one each in two areas) to 14 private players between 1995 and 1998.

The companies, referred to as the first and second cellular licensees had to pay a fixed annual licence fees that were mutually agreed upon during the bidding process. The bids were for a 10-year licence period and no upfront spectrum charges were levied. Later, they were allowed to migrate to the New Telecom Policy 1999 (NTP 99) regime, which featured a licence fee based on shared revenue from 1 August 1999. Amidst all these convoluted rules and regulations, mischief was afoot.

The CMTS operators had two cellular licences given for each of the four metropolitan cities of Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai, based on prescribed criteria with licence agreements signed in November 1994. There was a fixed licence fee prescribed by the DoT that wanted spectrum usage charges to be paid at applicable rates. The DoT placed a ceiling on tariff and call charges and operators in the metros were authorised to provide mobile telephone service conforming to GSM technology. A ‘cumulative maximum’ spectrum of up to 4.5 Mhz in the bands 890-902.5 and 935-947.5 (GSM 900 MHz band) was permitted.

This, as one has seen (read here), meant nothing and the winning bidders got double of what was mentioned in the licence agreement with more windfall gains to follow (See Table 3 below)

[caption id=“attachment_327031” align=“alignleft” width=“600” caption=“Table 3”]  [/caption]

There was much angst amongst the losing bidders and a massive legal battle ensued. Tata Cellular, which was originally selected for Delhi, had been left out and preferred a special leave petition (SLP [Civil] [Nos. 14191-94 of 1993]), the judgment revealing how murky and vitiated the process actually was. All was, however, forgotten in the excitement of India going mobile and as the country was getting used to the idea of the cellphone, someone was getting used to the idea of stealing spectrum.

For the record, the government issued licenses for cellular mobile services for Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai under a duopoly (not more than two cellular mobile operators for each circle). The duopoly scheme had a fixed licence fee regime for 10 years. The total amount payable by Bharti and Sterling for the Delhi circle, for instance, would be Rs 28 crore for the first three years, after which the licence fee would be payable at the rate of Rs 5,000 per subscriber per year. There was also a permitted rental charge of Rs 156 per subscriber per month on the basis of which the licencees were selected.

This is important because the amount that the operator could charge the subscriber was restricted to Rs 156 plus a Rs 16 per one-minute call; an arrangement that was drastically changed later. Interestingly, BPL and Hutchison Max paid much more for the Mumbai circle; Rs 42 crore for the first three years. Modi Telstra and Usha Martin paid a modest Rs 21 crore for the Kolkata circle while RPG Cellular and Skycell paid an even lower Rs 14 crore for the Chennai circle.

Having breached the ‘cumulative maximum’ barrier, the government proceeded with more giveaways in 1995 with bids for circles (states) for a period of 10 years, again with a cumulative maximum of 4.4 Mhz of spectrum per bidder being given. The next phase followed in 2001 with licences bundled with spectrum being given for the fourth operator (the third operator being the government) where the terms were changed: now the maximum spectrum that could be allotted would be 4.4 Mhz plus 4.4 Mhz subject to a maximum of 6.2 Mhz plus 6.2 Mhz. In the fourth round of bidding, the government brought in the wireless in local loop (WLL) operators on the same platform as the licences issued in the third round (in 2001), by when the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) headed by Atal Behari Vajpayee was in power.

How was the issuance of the first round of licences vitiated? The licensees were to pay Rs 5,000 per subscriber per year from the fourth year (that worked out to Rs 417 per month x 12). Here is when chicanery took place: The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, which had been set up in 1997, agreed to a curious proposal. The initial permitted charge of Rs 156 per subscriber per month, on the basis of which the licencees were selected, was suddenly enhanced to Rs 600 per month.

This meant that the subscriber would pay more than three times the original charge while the per call charge of Rs 16 per minute was brought down to Rs 6, making nonsense of the arithmetic on the basis of which the licences were secured and giving the operators a windfall gain. No questions were asked. How did the operators secure this bonanza?

[caption id=“attachment_327043” align=“alignleft” width=“600” caption=“Table 4”]  [/caption]

( SeeTable 4 above) shows how by raising the subscriber fee to Rs 600, the government made it possible for the operators to pass on the entire extra payment burden on to the subscriber. Ordinary subscribers, or users of mobile phones, paid the money and the operators just raked it in. Indeed, they would make Rs 100 per subscriber and even if the per call charge was zero, they would make money.

Janta maree gayee (‘ordinary people have been massacred’) was the popular refrain among bigwigs of telecom companies who watched gleefully from the sidelines. The janta had no voice (save that he could have expensive conversations), the operators made merry; their bottomlines had come alive with a positive Rs 183 per subscriber per month from a negative one (-) Rs 260.

One may well point out that it was the government that permitted such changes but that does not make the changes honourable. One may also say that the operators could not pull off such high rates and could hold them for limited slabs and for a very short period of time.

The point is that such ridiculous rates were cleared by the government. At whose behest? Good question!

(Tomorrow: How changed licence terms enabled telcos to make a quiet killing)

(Read Part I and Part II of this series)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)